By Andrea Cronin, Reader Services

I went to Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka) this morning. The flight from Boston normally costs upwards of $1,000. Flight time, with layovers, averages 24 hours. However my trip to Ceylon did not cost me a dime or any flight time. I went on a “mind vacation.” The concept sounds a little quirky but a mind vacation is a great way to visit another place or time without actually spending the money for a flight or inventing time travel. (Although if you are currently devising time travel, I want in.)

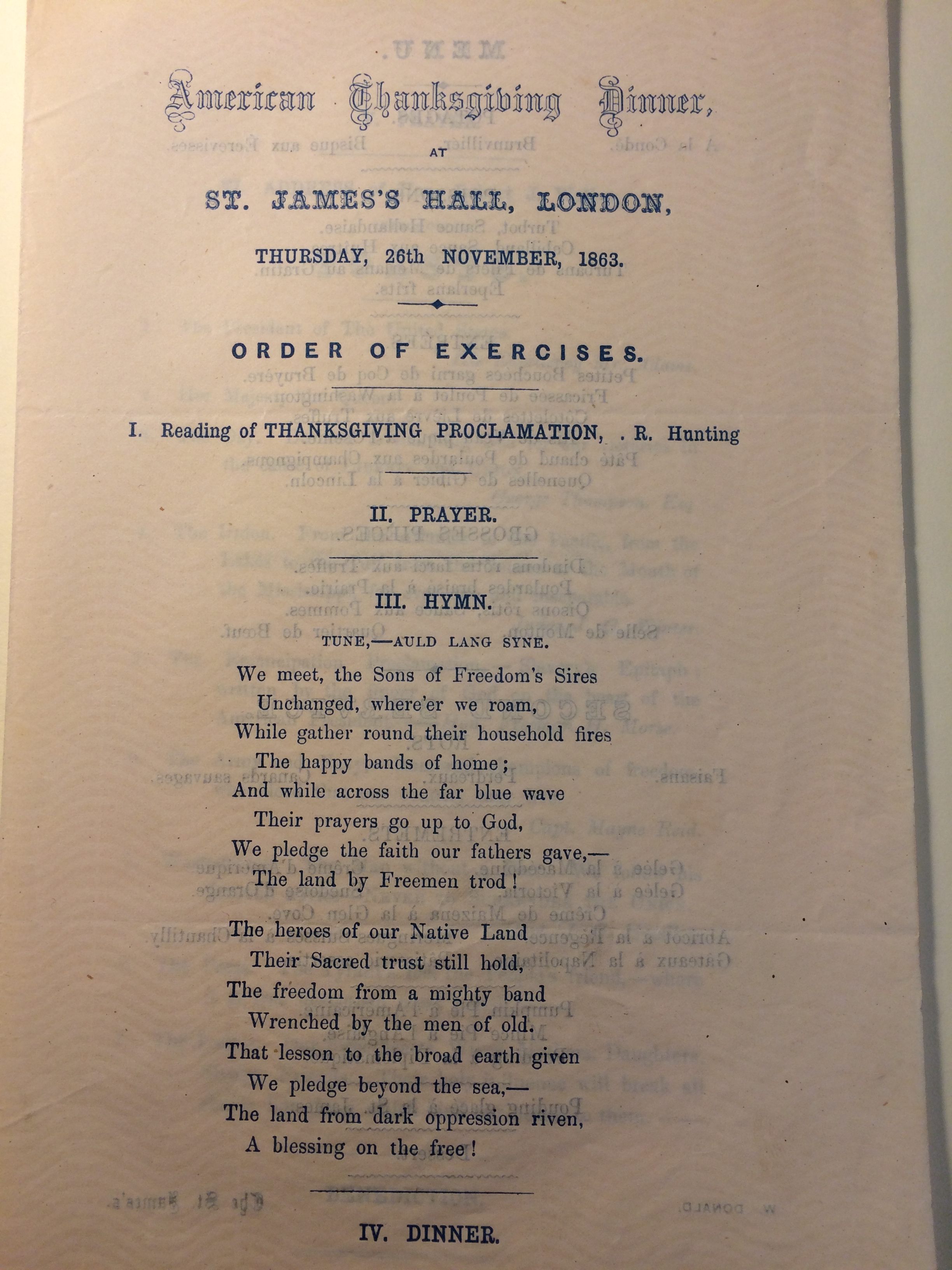

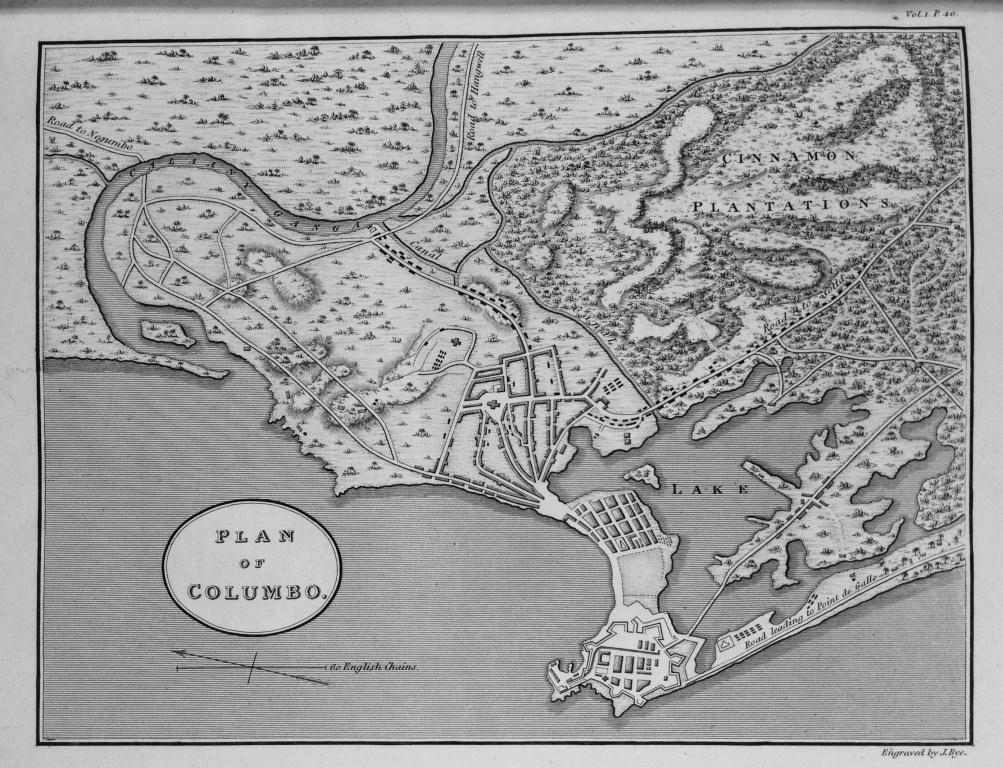

My mind vacation materialized as I read Reverend James Cordiner’s Description of Ceylon. In these two volumes, Cordiner recorded his experiences in Ceylon while serving as chaplain to the garrison of the capital Colombo from 1799 to 1804. The first volume contains descriptions of the island’s geography, resources, inhabitants and climate. When I first read the climate description of Colombo, thoughts of the brisk January temperatures in Boston today — and the approaching blizzard — simply melted away.

With great detail, Cordiner contrasts the climate of Colombo with the nearby British trading port of Madras (modern day Chennai, India). “…with the arid plains, withered vegetation, scorching winds, and clouds of burning dust, which, for several months in the year, cast an inhospitable gloom around the vicinity of Madras. There in, the month of May, 1804, Farenheit’s thermometer appeared above ninety degrees before nine o’clock in the morning, and, in the course of the day, rose in many houses to one hundred and nine degrees.” Cordiner considers this port’s climate to be lacking. I also think Madras is a little too hot and dusty for a comfortable mind vacation.

I find his description of Colombo comparatively restorative to read in the middle of January. “The smallest inconvenience from heat is never felt within doors at Columbo. Even passing through this moisture under the full blaze of the meridian sun, the air is ten degrees cooler that than of Madras … There is then always a fresh breeze from the sea, which greatly lessens the effects of the sun’s power.” Colombo is a tropical vacation compared to dusty Madras — and snowy Boston! With temperatures in the 80s and a sea breeze, who would not want to visit?

Do you need a mind vacation this week? I encourage you to visit our reading room (although check our homepage, as we may close due to snow) for a mind vacation to plenty of local and distant destinations throughout the centuries available in our collections. I would love to hear your adventures.