By Dan Hinchen

Filibuster, n. 1. An irregular military adventurer, esp. one in quest of plunder; a freebooter; — orig. applied to buccaneers infesting the Spanish American coasts; later, an organizer or member of a hostile expedition to some country or countries with which his own is at peace, in contravention of international law.

On September 12, 1860, an American lawyer and journalist, an adventurer and filibuster, was executed by firing squad in Trujillo, Honduras. This is his story in brief.

William Walker was born in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1824. Pushed by his parents to a good education, he graduated from the University of Nashville at the age of 14. By 1843, at 19, Walker received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. He continued his medical education in Paris and toured several cities in Europe before returning to Nashville to practice.

Dissatisfied with his career in medicine, Walker changed his focus to law and, shortly after taking up studies, moved to New Orleans. While he attained the bar in Louisiana, his practice there was even briefer than his medical practice and he soon moved into the field of journalism. In the winter of 1848, Walker became an editor and proprietor of the conservative New Orleans Crescent.

The following year, like so many other intrepid young men, Walker responded to the lure of the West and settled in San Francisco, arriving in June, 1850. He continued his work as a journalist, speaking loudly against the judicial authorities in San Francisco for failure to roll back a tide of lawlessness and crime. His vocal stance raised the ire of district judge Levi Parsons who declared the press a nuisance and, after much wrangling, judged Walker guilty of contempt and set a fine on him. Now, Walker’s legal experience came to the fore as he defended himself in open court against the charges, with much popular support, and was ultimately vindicated.

Shortly after, Walker moved to the nearby and quickly growing town of Marysville where he practiced law with Henry Watkins. By this time, many men of California were already engaging in filibustering in Latin America. This practice, prominent during the 1850s, was an aggressive and idealized effort to expand the influence of the United States in fulfillment of manifest destiny.

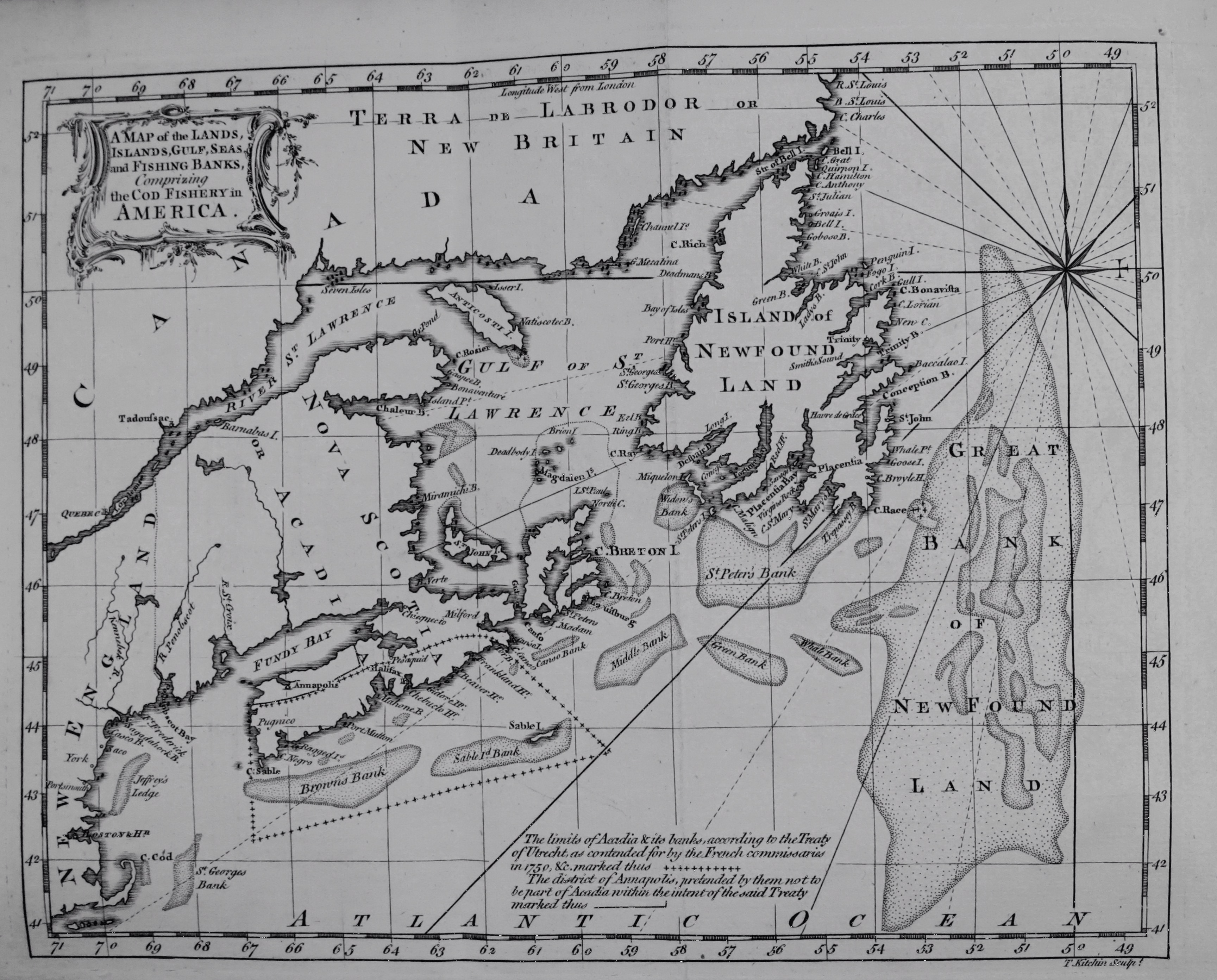

Over the next several years, Walker pursued this activity with fervor. In 1853 he attempted an invasion of Mexico with a small band of men, barely escaping alive. The United States tried him in violation of the neutrality act but he was quickly exonerated. In 1855, he set his sights on Nicaragua. This locale was coveted by many as the key to linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. No less a man than Cornelius Vanderbilt invested heavily in transporting goods across the narrow country.

Landing with a small force of Americans, Walker supplemented his force with sympathetic liberal Nicaraguans and demanded independent command. With a lot of luck and small amount of daring, Walker and his men took the city of Granada and made hostages of its conservative leaders.

Over the next several months, Walker used various schemes and local proxies to consolidate power in his own hands, eventually raising the alarm in neighboring Central American countries. In April 1856, Costa Rica occupied the Nicaraguan city of Rivas in order to drive Walker out but, with the aid of an outbreak of cholera, he forced them into retreat.

Throughout the next year, Walker’s course of action greatly alienated him from his supporters in American business. So it was with the financial backing of Vanderbilt that, in spring of 1857, an alliance of Central American countries besieged him at Rivas, forcing him to surrender to an American naval officer, at which time he and his men were delivered out of the country.

Still, he was not finished. By this time, Walker was something of a folk hero in the United States, meeting acclaim wherever he went. In November 1857, he tried to invade and was met by the US Navy which forced a quick surrender. In 1860 he made one last effort. This time, the Royal Navy captured him and delivered him to the nearest authorities, the Hondurans. In September of that year, William Walker finally met his end.

The story of William Walker was unknown to me until I recently watched a film from 1987 called simply Walker, with Ed Harris in the title role and directed by Alex Cox. Though a fictional take on the actions of the man, it raised my awareness and piqued my curiosity. If you are interested in learning more about Walker and other 19th century filibusters, see below for some resources

Sources at the MHS

– The destiny of Nicaragua: Central America as it was, is, and may be, Boston: S.A. Bent & Co., 1856.

– Scroggs, William O., Filibusters and financiers: the story of William Walker and his associates. New York: Macmillan, c1916.

– Wells, William V., Walker’s expedition to Nicaragua…, New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1856.

Useful online resources

– Stiles, T.J., “The Filibuster King: The Strange Career of William Walker, the Most Dangerous International Criminal of the Nineteenth Century,” History Now 20 (Summer 2009). The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.gilerlehrman.org/history-by-era/jackson-lincoln/essays/filibuster-king-strange-career-william-walker-most-danerous-i

– Tirmenstein, Lisa, “Costa Rica in 1856: Defeating William Walker While Creating a National Identity,” Accessed March 12, 2015. http://jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu/FieldCourses00/PapersCostaRicaArticles/CostaRicain1856.Defeating.html

– Judy, Fanna, “William Walker,” The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, Accessed March 12, 2015. http://www.sfmuseum.org/hist1/walker.html

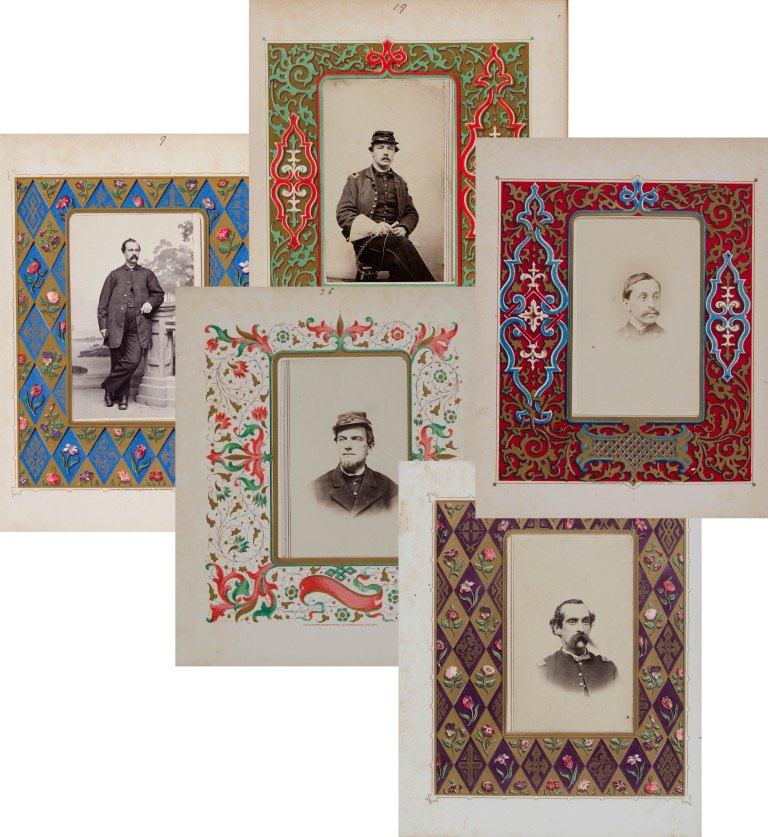

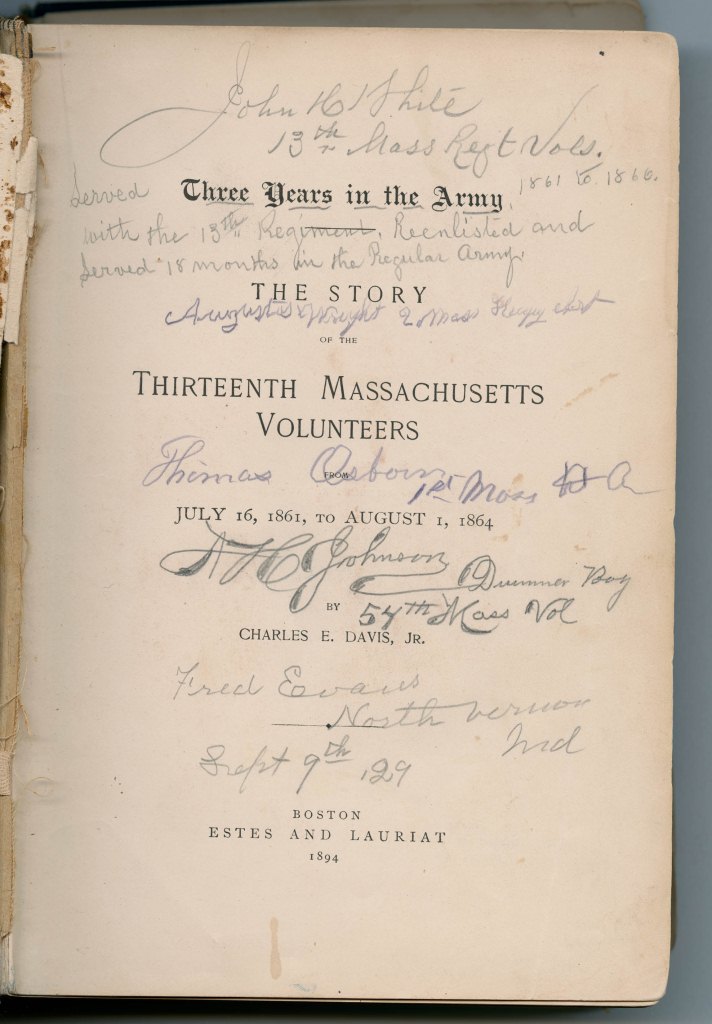

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

Title page autographed by veterans of other regiments

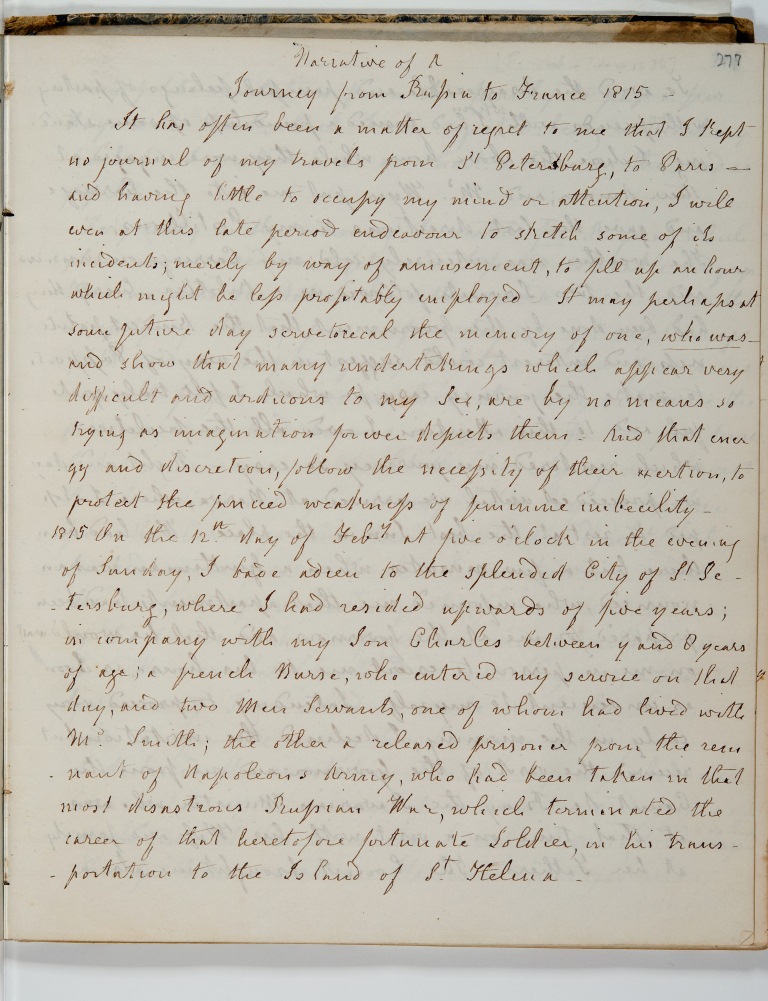

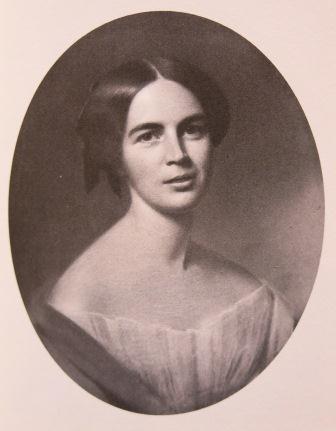

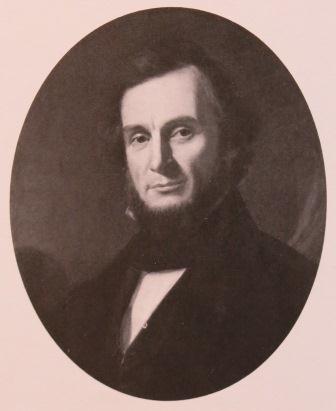

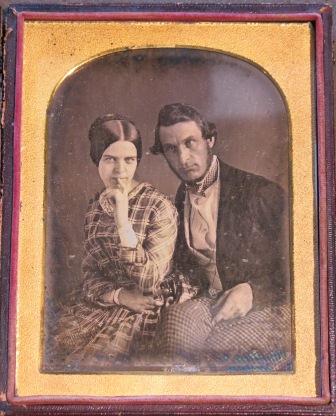

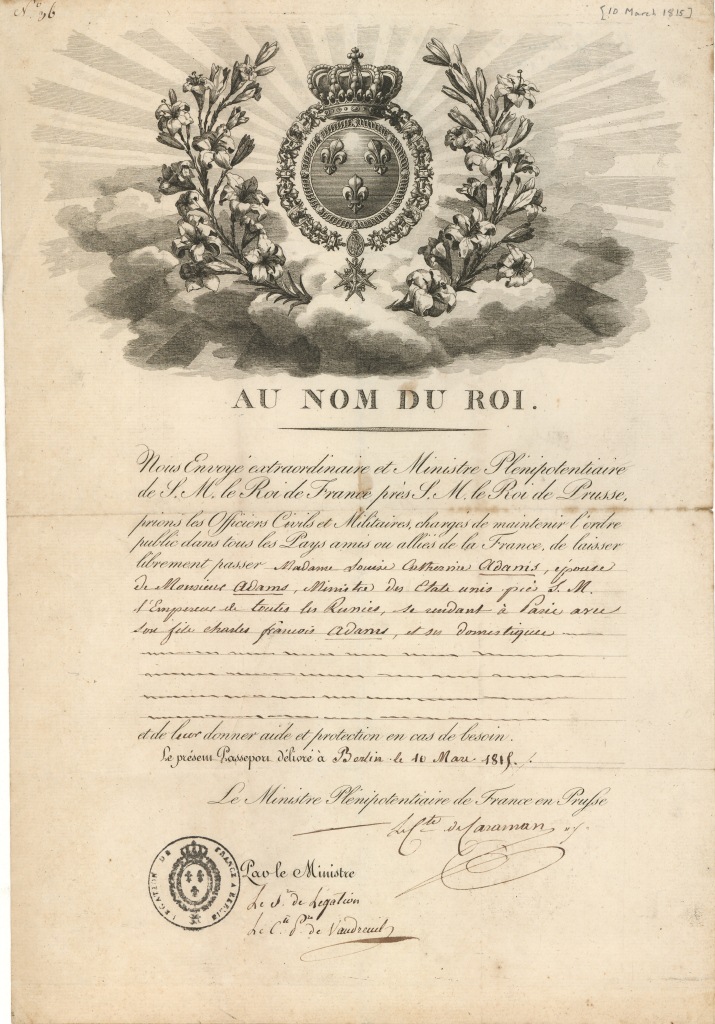

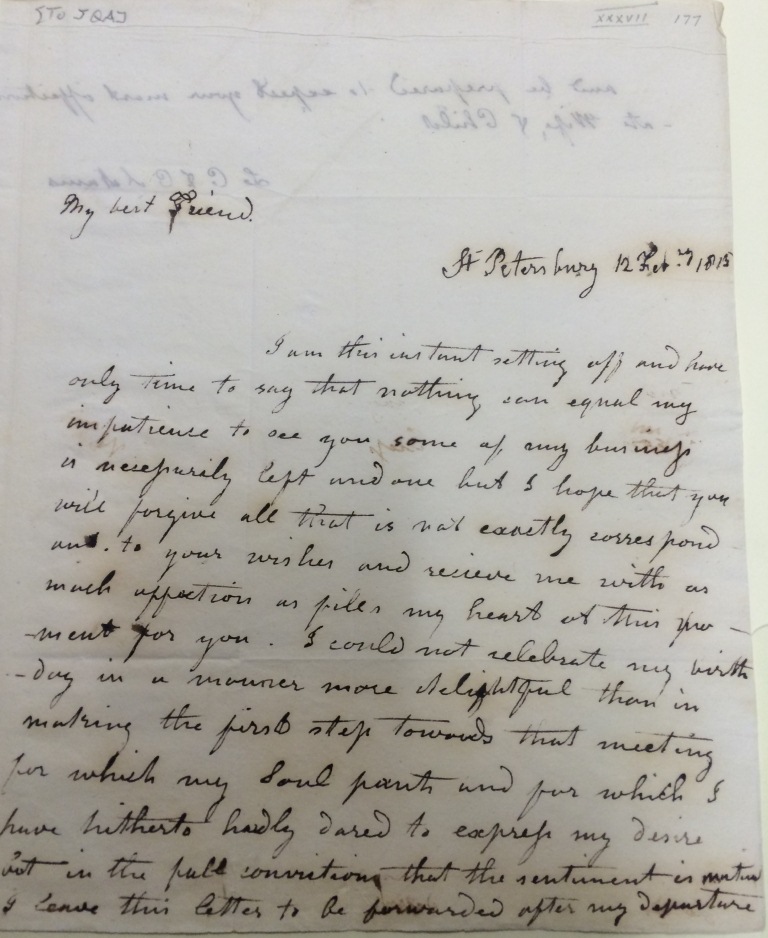

This month marks the 200th Anniversary of Louisa Catherine Adams’s six-week and nearly 2,000-mile trip from St. Petersburg, Russia, to Paris, France. Travelling by carriage across a war-torn Europe and in the midst of Napoleon’s Hundred Days after his escape from his exile on Elba, trying to reach her husband, John Quincy, who, negotiating an end to the War of 1812 in Ghent, she had not seen for a year, Louisa’s story is an amazing one.

This month marks the 200th Anniversary of Louisa Catherine Adams’s six-week and nearly 2,000-mile trip from St. Petersburg, Russia, to Paris, France. Travelling by carriage across a war-torn Europe and in the midst of Napoleon’s Hundred Days after his escape from his exile on Elba, trying to reach her husband, John Quincy, who, negotiating an end to the War of 1812 in Ghent, she had not seen for a year, Louisa’s story is an amazing one. lost carriages, and news of murders on the roads she was travelling. Still she recalled the scenes she passed in her retrospective

lost carriages, and news of murders on the roads she was travelling. Still she recalled the scenes she passed in her retrospective