By Susan Martin, Collection Services

The Hall-Baury-Jansen family papers at the MHS include ten small diaries kept in Pine Bush, N.Y. between 1858 and 1878. Most of them belonged to a young farmer named John Egbert Jansen, but three were written in another, unidentified hand. By checking the diaries against each other, I was able to confirm that the second diarist was John’s wife, Margaret A. (Wisner) Jansen.

John and Margaret weren’t married until 1862, but both kept diaries in 1858 and 1859, during their courtship. A side-by-side comparison of these two years makes for some fun reading. Both John and Margaret wrote in their diaries every day, and while the entries are short, repetitive, and often dry, taken as a whole, they give us a glimpse into the couple’s relationship as it develops. And it’s hard to resist speculating on what some of the more elusive entries mean.

At the beginning of 1858, Margaret was a lonely young woman of 17. She disliked the days she spent at home alone and was disappointed when she received no letters or visits. Some of her early diary entries are forlorn: “I do wonder if any body likes me.” Her first reference to John comes on 21 January 1858: “To tea with J.E. Nice visit.” His entry for that date doesn’t mention her, but that was apparently the day he decided to “quit chewing tobacco.” (Coincidence? Hmm.) A week later, Margaret wrote that John “called for a singing book.” The corresponding entry in John’s diary discusses other matters before noting that he “made a call.” This circumspect little phrase was almost invariably the way he described his visits to Margaret.

The relationship of the young couple was moving along, and when he visited, she often had “a real funny time,” while he enjoyed himself “very much” or “finely.” He even helped with chores around her house. It’s possible that Margaret and John had known each other for years, if not their whole lives, considering how small the town of Pine Bush was. The Wisners and the Jansens ran in the same social circles and attended the same church and many of the same events. These included singing school, bible class, lectures, and parties. On 15 March 1858, Margaret attended a party at the home of John’s aunt and stayed until the wee hours of the morning. Her entry for that date reads: “Went to a party to Mrs. Jane Jansens. Had a splendid time. Saw ___. Came home about four A.M.” He wrote more succinctly that he “staid all night.”

John began calling at Margaret’s house more frequently, often multiple times a week. She now expected his visits and made a note in her diary when he didn’t come. But of course their relationship, like all others, had its rocky patches. Margaret sometimes doubted that her feelings were reciprocated. Once she complained: “I think I may easily say I am thinking of those who think not of me & perhaps care not for me. I have one in my mind.” Other days, she was more dreamy and sanguine and “had some very pleasant thoughts.” One wistful entry just trails off: “Freligh Lyon called. I wish – ” And she still had those downcast days: “Did various little things. Took a little walk in the evening. Here on the rock I post this thinking, looking, all alone.”

If only she could have read John’s diaries! While he was more subdued in expression and less confessional in tone, he definitely thought she was “pleasant” and “agreeable.” He wrote happily about joining her and her friends on fishing trips and picnics. He still referred to her coyly as “a companion” or just by initials or a blank line, but we can use her diary to confirm that he did, in fact, mean her. And she might have been interested to know how disappointed he was the day she didn’t attend church and he felt “some what forgotten.” The end of the year made him philosophical: “Where will I be next year this time? I would like to know. I do not know! Do you?”

At the beginning of 1859, there was trouble in paradise, and the two different perspectives sometimes present a startling contrast. John thought his 1 Mar. 1859 visit to Margaret was “pleasant,” but she wrote: “J.E. called. Was much out of humor.” (I don’t know if she meant John or herself.) On another visit, she thought he was “very anxious to get away. Can’t say why.” He described some of the calls he made to her that spring as “miserable,” even “disgusting.” Neither wrote explicitly about their problems, but Margaret did confess that “one will get provoked occasionally.”

Whatever their differences, the couple rode them out, and their diaries contain many endearing, if terse, references to each other. She wished his visits lasted longer: “Johnie called, one minute. Always in a hurry.” For that matter, so did he: “Made a call. Sorry could not stay. Sorry to leave indeed.” He began to call her “Maggie” near the end of 1859, and her lonely days seemed to be a thing of the past. Her diary entry for 6 August 1859 reads, in part: “This is a good world but some mighty quear people in it.” Along the side of the page, she added, apparently later: “Some very nice good ones too.”

Reading John and Margaret’s diaries side-by-side also paints a picture of a typical man and woman of the time. While she spent days cleaning, sewing, and doing other housework, he was working on his farm, haying, logging, etc. It’s a rare treat to see two lives lined up so perfectly, each diary fleshing out and enriching the other to create a fuller picture…not to mention giving us a little peek at what these two young people really thought of each other!

and

and

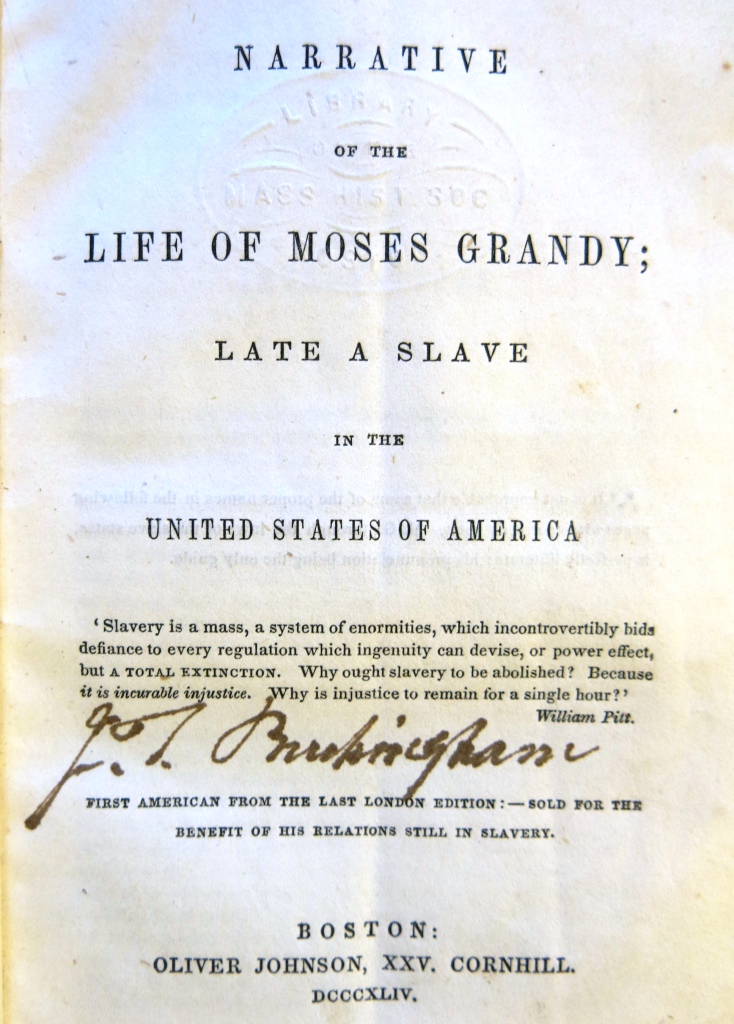

The story of Grandy’s life, written down by noted abolitionist George Thompson and first published in 1843, became popular with the abolitionist movement both in the United States and abroad. Grandy’s story, like a number of other slave narratives including those of Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northrup, served to illustrate for a wide audience the cruelties of slavery and the outrages endured by those kept in bondage. Stories of this kind helped to spread the message of abolitionism far and wide in the decades prior to the American Civil War.

The story of Grandy’s life, written down by noted abolitionist George Thompson and first published in 1843, became popular with the abolitionist movement both in the United States and abroad. Grandy’s story, like a number of other slave narratives including those of Frederick Douglass and Solomon Northrup, served to illustrate for a wide audience the cruelties of slavery and the outrages endured by those kept in bondage. Stories of this kind helped to spread the message of abolitionism far and wide in the decades prior to the American Civil War.