By Susan Martin, Collections Services

I’ve written many posts at the Beehive highlighting specific items, stories, and people from our collections that captured my attention, but it occurs to me that readers of our blog may be interested in a bigger picture of the work we do here. This week, I’d like to offer a behind-the-scenes look at how a collection is processed—or, as we say in Collections Services, how the sausage is made.

The responsibilities of the MHS Collections Services department include everything from the acquisition of new material to processing, preservation, and digitization. It’s the job of a manuscript processor like me to make collections both physically accessible and intellectually coherent to researchers, what archivists refer to as “arrangement and description.”

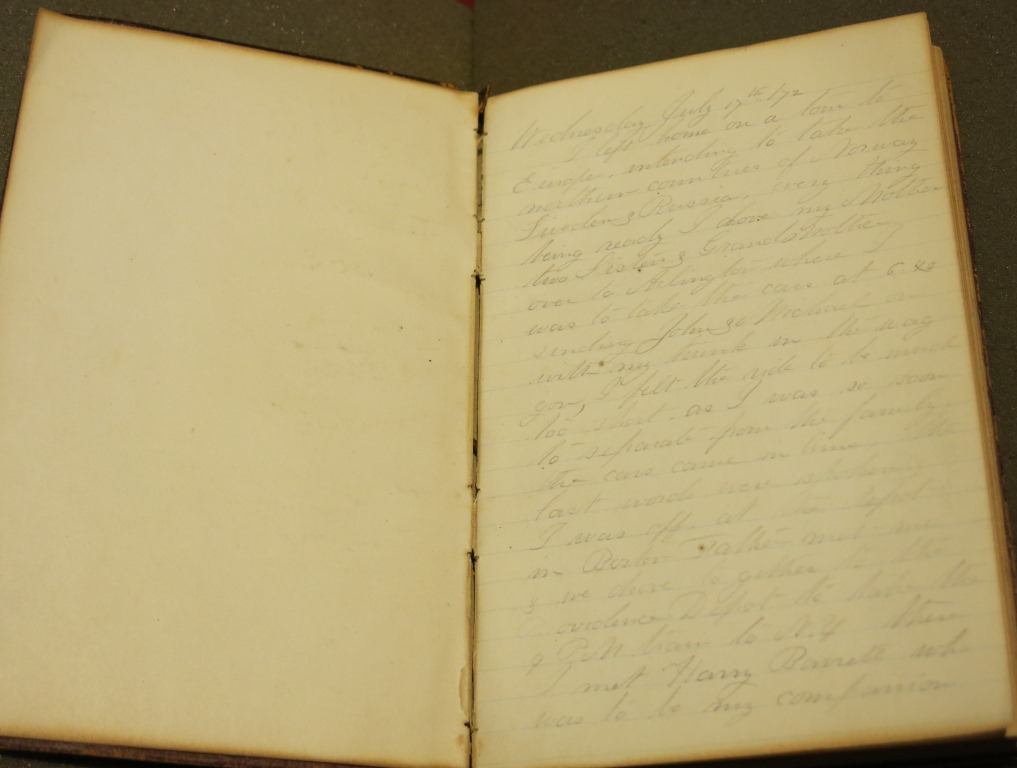

This can be challenging, to say the least. Collections come to us in all shapes, sizes, and conditions. Think of the way you keep your personal files at home or on your computer. You may know where things are, but would anyone else be able to figure it out? Are items arranged chronologically? Do folder labels really reflect the folders’ contents? How do the files relate to each other? When we’re talking about historical documents, often passed down through generations, potential problems multiply. Items may be in poor condition, undated, unidentified, basically a mess. For example:

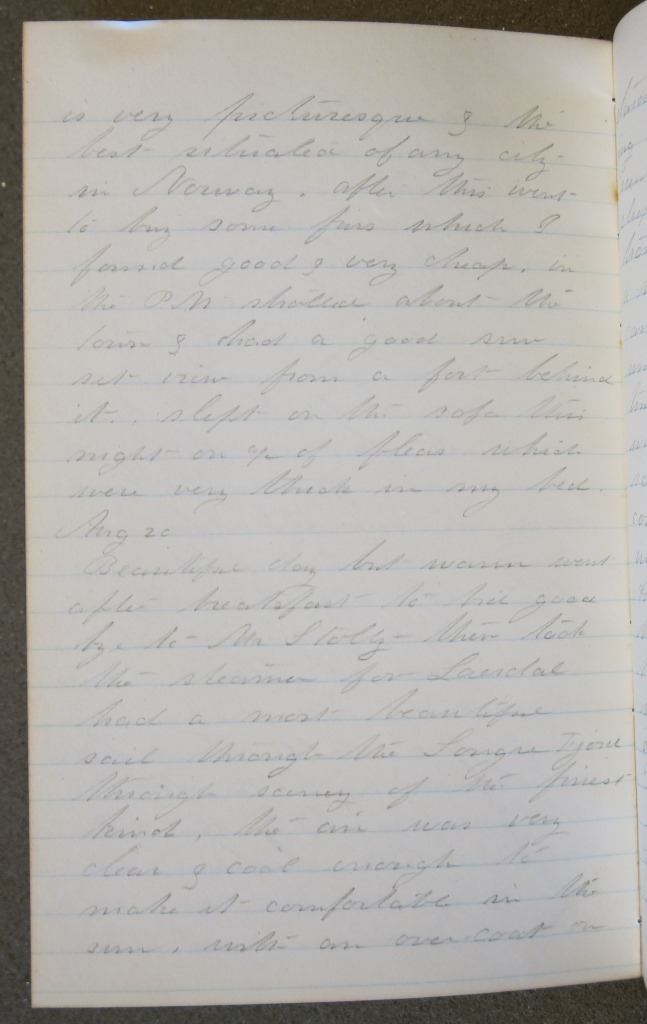

This carton contains hundreds of letters folded up in their original envelopes and in no discernible order, as well as rusty staples, paper clips, and who knows what else. (Hair, leaves, dead insects—we’ve found them all!) These papers can’t be used by researchers like this. Each letter will need to be unfolded and arranged chronologically in acid-free boxes and folders for access and long-term preservation. It’s a very time-consuming job. A finished collection ends up looking something like this:

At the same time this physical work is being done, the processor will also need to make some intellectual sense of the material, scanning the letters carefully but quickly to determine who the authors and recipients are and what topics they discuss. The collection will be described in ABIGAIL, our online catalog, with headings for people, places, organizations, events, subjects, etc.

Good cataloging is vital because it’s our description that directs researchers to a specific collection. Experienced archivists have developed both subject knowledge and professional instincts that help them make informed judgments about the context and importance of a collection. What makes the papers historically significant? What possible avenues of research might bring someone to see them?

When you look at one of our catalog records, you may notice many slightly different permutations of the same topic. For example, papers of the director of Boston’s Children’s Hospital during the peak of the U.S. polio epidemic might be described by any or all of the following subject headings (and then some):

Children’s Hospital (Boston, Mass.).

Children—Diseases.

Children—Health and hygiene.

Children—Hospitals—Massachusetts—Boston.

Hospital administrators.

Hospitals—Administration.

Hospitals—Massachusetts—Boston.

Poliomyelitis.

This may seem redundant, but there’s a method to the madness. What headings are useful depends on a researcher’s particular area of interest. Is he or she doing work on the specific hospital, children’s hospitals, Boston hospitals, hospital administration, polio, general childhood health?

Catalog records for manuscript collections have to be written from scratch because each collection is unique. No two archivists will describe the same papers the same way. Hundreds of our collections here at the MHS are also described more fully in online guides, which allow us to go into more detail about groups or “series” of papers and to indicate where specific material is located. Our guides are fully searchable, and more and more people are finding us through online search engines.

Manuscript processing is fundamental to all the work done at the MHS. Every other function of the library, from research to digitization, exhibit planning, even blogging, would not be possible without it. We’re constantly refining our catalog records and collection guides, and we’re still making discoveries in collections that have lived on our shelves for years. Our researchers are a great resource, bringing their subject knowledge to bear to fill gaps…and to catch our mistakes!