By Amanda Norton, Adams Papers

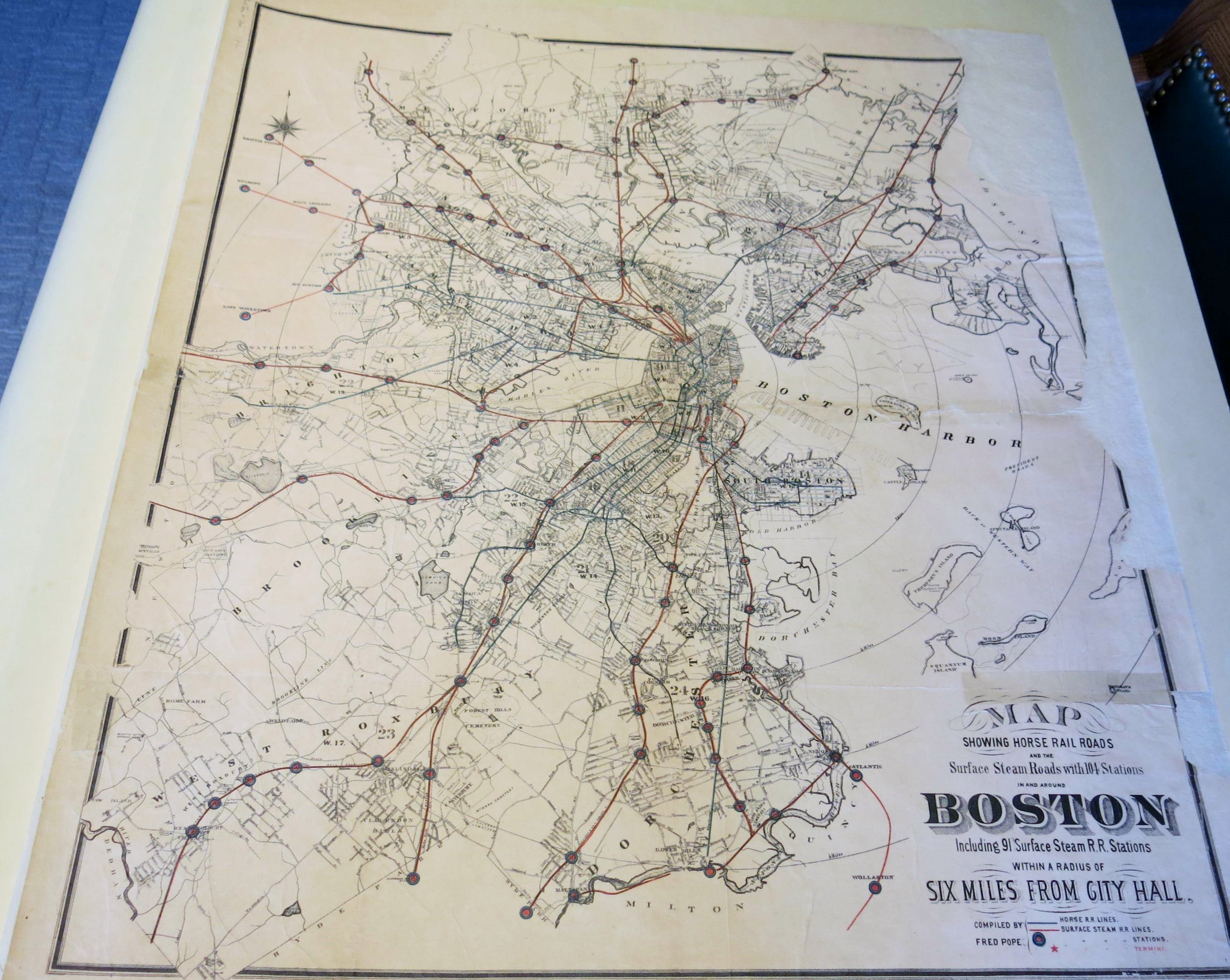

In the fall of 1773, three ships carrying a cargo of tea from the British East India Company were on their way into Boston Harbor. Subject to the Tea Act of 1773, allowing the tea to be unloaded in Boston would have meant the acceptance of the principle of Parliamentary taxation, an idea that Bostonians had been fighting for a decade. After Governor Thomas Hutchinson and the ship owners refused to prevent the ships’ landing, the Sons of Liberty decided to take action, and 242 years ago on the night of December 16, a group of patriots wearing Native American dress snuck on board the three ships and dumped their cargo into the harbor.

The next day, budding patriot John Adams wrote to his friend James Warren enthusiastically about the audacious stroke: “The Dye is cast: The People have passed the River and cutt away the Bridge: last Night Three Cargoes of Tea, were emptied into the Harbour. This is the grandest, Event, which has ever yet happened Since, the Controversy, with Britain, opened!” He added, “The Sublimity of it, charms me!”

“The People should never rise, without doing something to be remembered—something notable And striking.” he noted in his diary. “This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid and inflexible, and it must have so important Consequences, and so lasting, that I cant but consider it as an Epocha in History.” “The Question is whether the Destruction of this Tea was necessary?” he queried. “I apprehend it was absolutely and indispensably so.”

In his letter to Warren, Adams looked ahead as to what would follow this momentous affair. “Threats, Phantoms, Bugbears, by the million, will be invented and propagated among the People upon this occasion. Individuals will be threatened with Suits and Prosecutions. Armies and Navies will be talked of—military Execution—Charters annull’d—Treason—Tryals in England and all that—But—these Terrors, are all but Imaginations. Yet if they should become Realities they had better be Suffered, than the great Principle, of Parliamentary Taxation given up.”

There were indeed serious consequences for the people of Boston in the form of the Coercive, or Intolerable, Acts levied by Parliament in retaliation. The harsh punishment backfired however. Colonists grew more unified in sentiment, and the calling of the First Continental Congress in 1774 was a pivotal step in the movement toward revolution and eventually, independence.

John Adams to James Warren, 17 December 1773, Warren-Adams Papers