By Anna J. Clutterbuck Cook, Reader Services

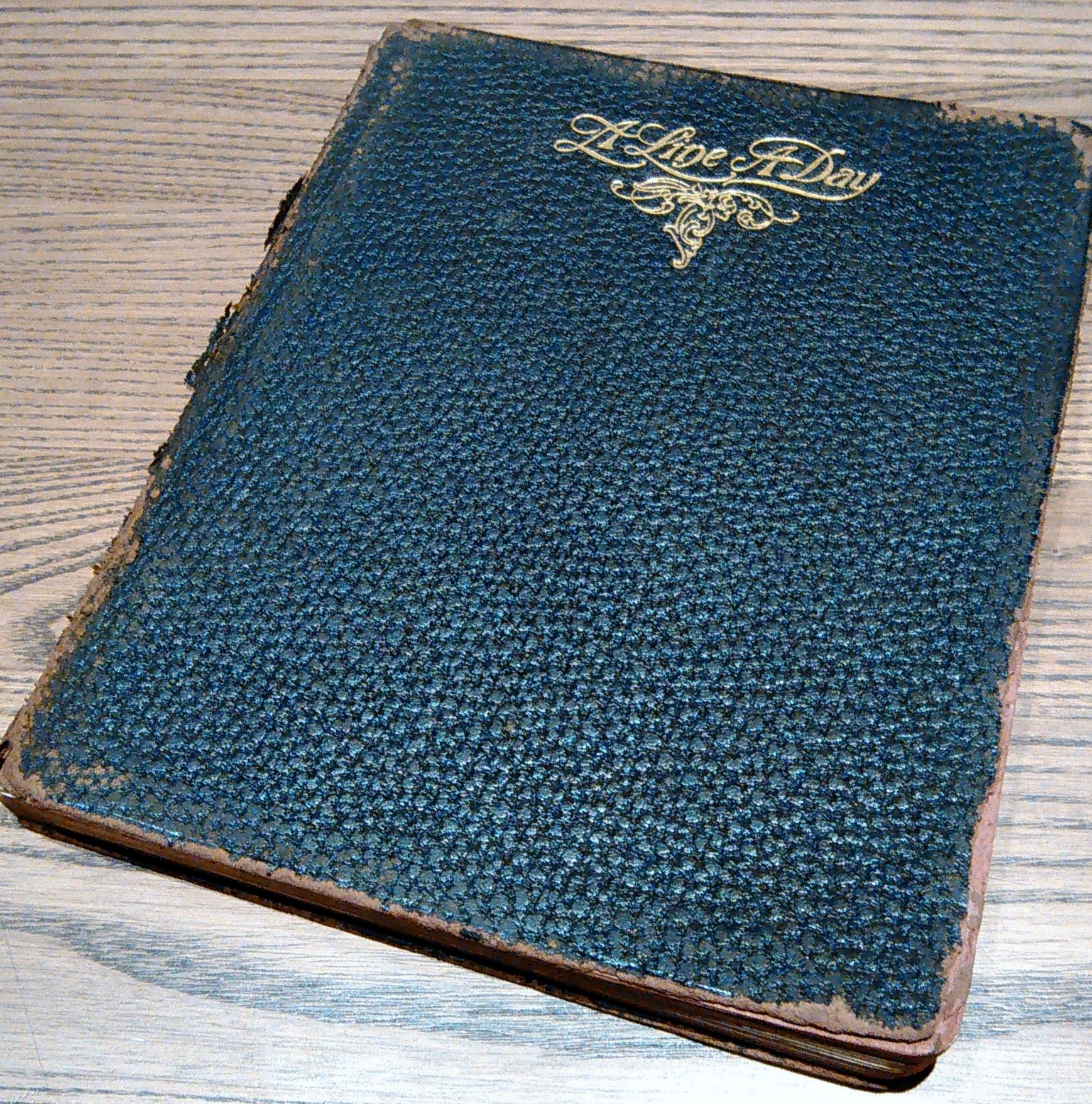

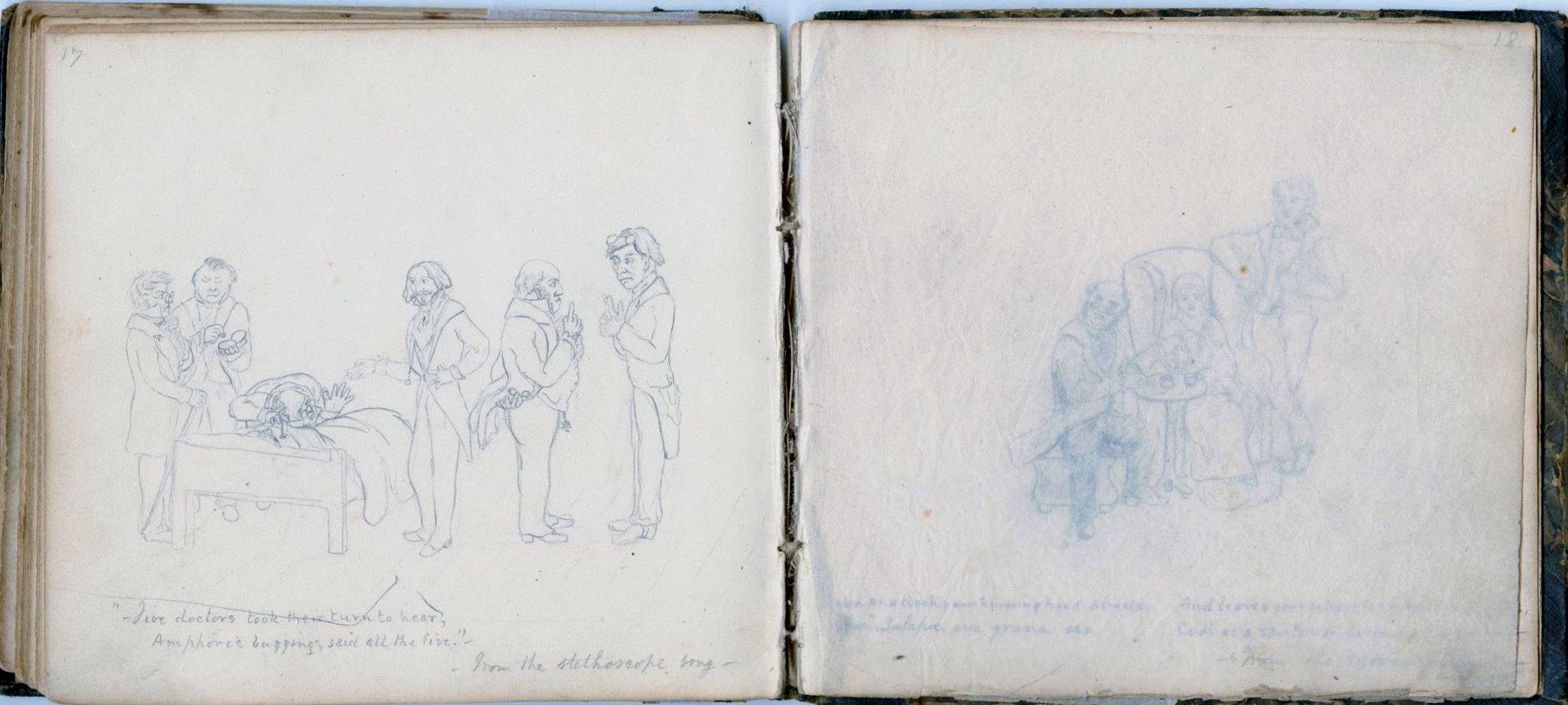

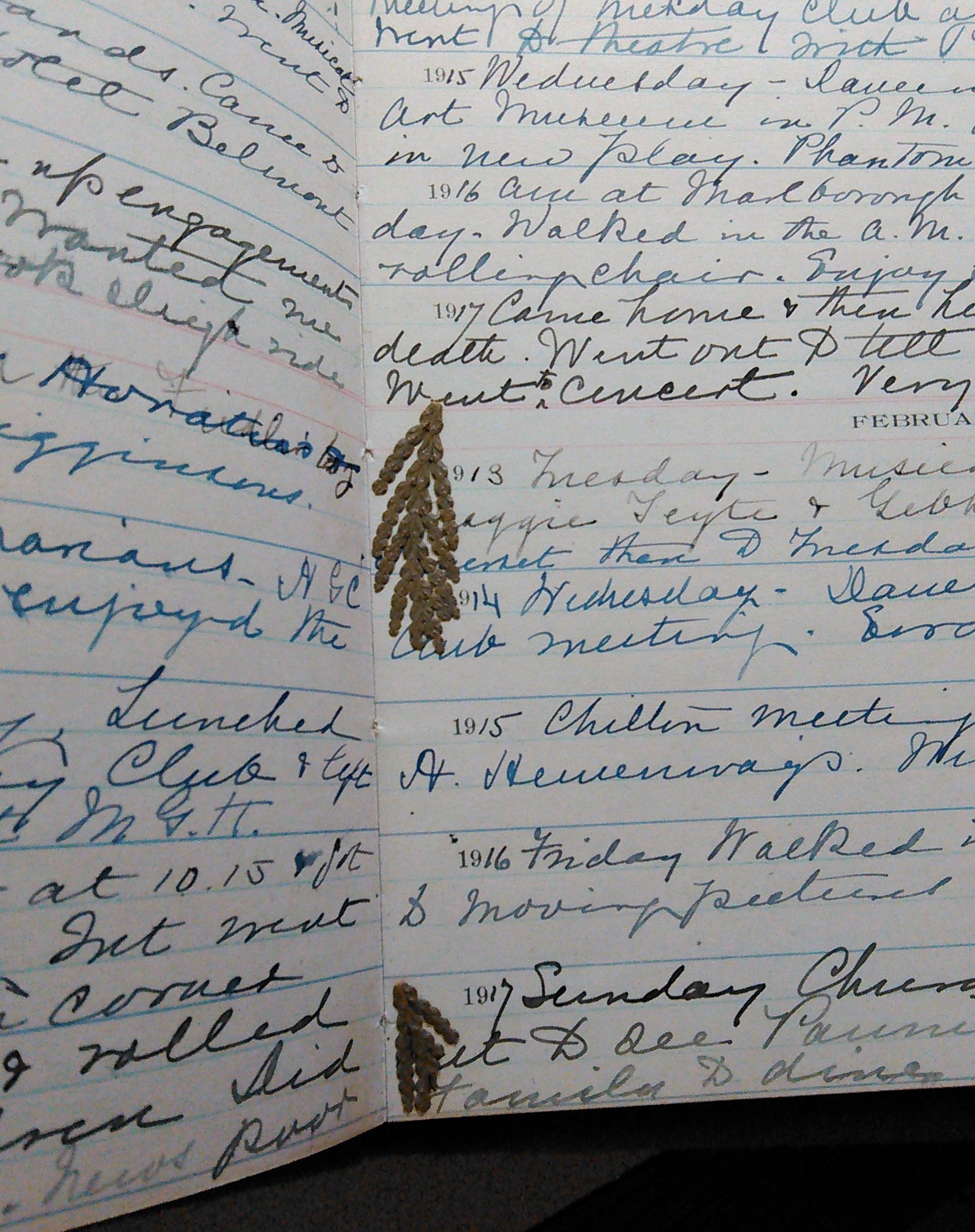

Today, we return to the line-a-day diary of Margaret Russell. If you missed the January installment of Margaret’s diary, you can find it here, along with a brief introduction to this monthly series.

During the month of February 1916, Margaret traveled south from wintery New England to Atlantic City by rail and spends nine days at the upscale Marlborough Blenheim hotel. While the weather in New Jersey was not particularly spring-like (“foggy and cold” reads one day, “sleeting” another), Margaret still walked daily and took in many local amusements including outdoor concerts and a performance of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion — first performed just three years earlier — starring the actress who is said to have provided the inspiration for Eliza Dolittle, Beatrice Stella Tanner (“Mrs. Pat”).

Where do you think she collected this bit of plant matter tucked between the diary pages?

* * *

February 1916

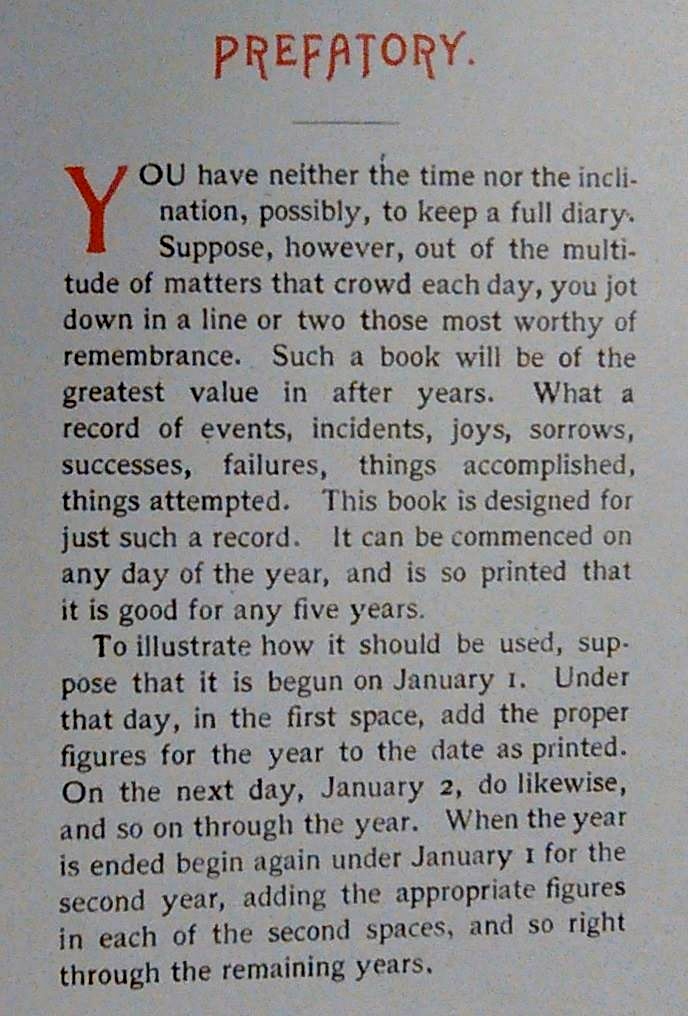

1 Feb.* Tuesday – Stay in bed every morning till 10.30.Feel better. Went to tell Dr.Balch so then to Friday Club. Miss Abler came to dine.

2 Feb. Wednesday – annual meeting of Chilton. Mrs.Ward’s class.Heavy snowstorm so did not go out again.

3 Feb Thursday- Heavy snowstorm.Clearing by 12 – took Mrs A–out in the P.M. for a short time. Feel better.

4 Feb. Friday – Concert. Geraldine [word]. Dined at Bowker’s with Prof & Mrs. Dupriez of [Belgium].

5 Feb. Saturday. Meeting & service at Good Samaritan. Bowker’s dinner another night not Friday

6 Feb. Sunday. Walked to Cathedral with Miss A & lunched at H.G.C.’s. Family to dine.

7 Feb. Monday. Lunched at Marian’s. Dined at Cousin Edith Perkins’ to meet Mrs. James Perkins.

8 Feb. Monday – Packing & errands. Came to N.Y. on the 3 o’k train. Went to Hotel Belmont.

9 Feb. Left for Atlantic City at 10.15 & got there for lunch. Morning [word] went out to walk. Lovely rooms [word].

10 Feb. Am at Marlborough Blenheim. Pleasant day. Walked in the A.M. Sat out & then took Hollingchair. Enjoy salt water baths.

11 Feb. Friday. Walked in the morning. Went to moving pictures in the P.M.

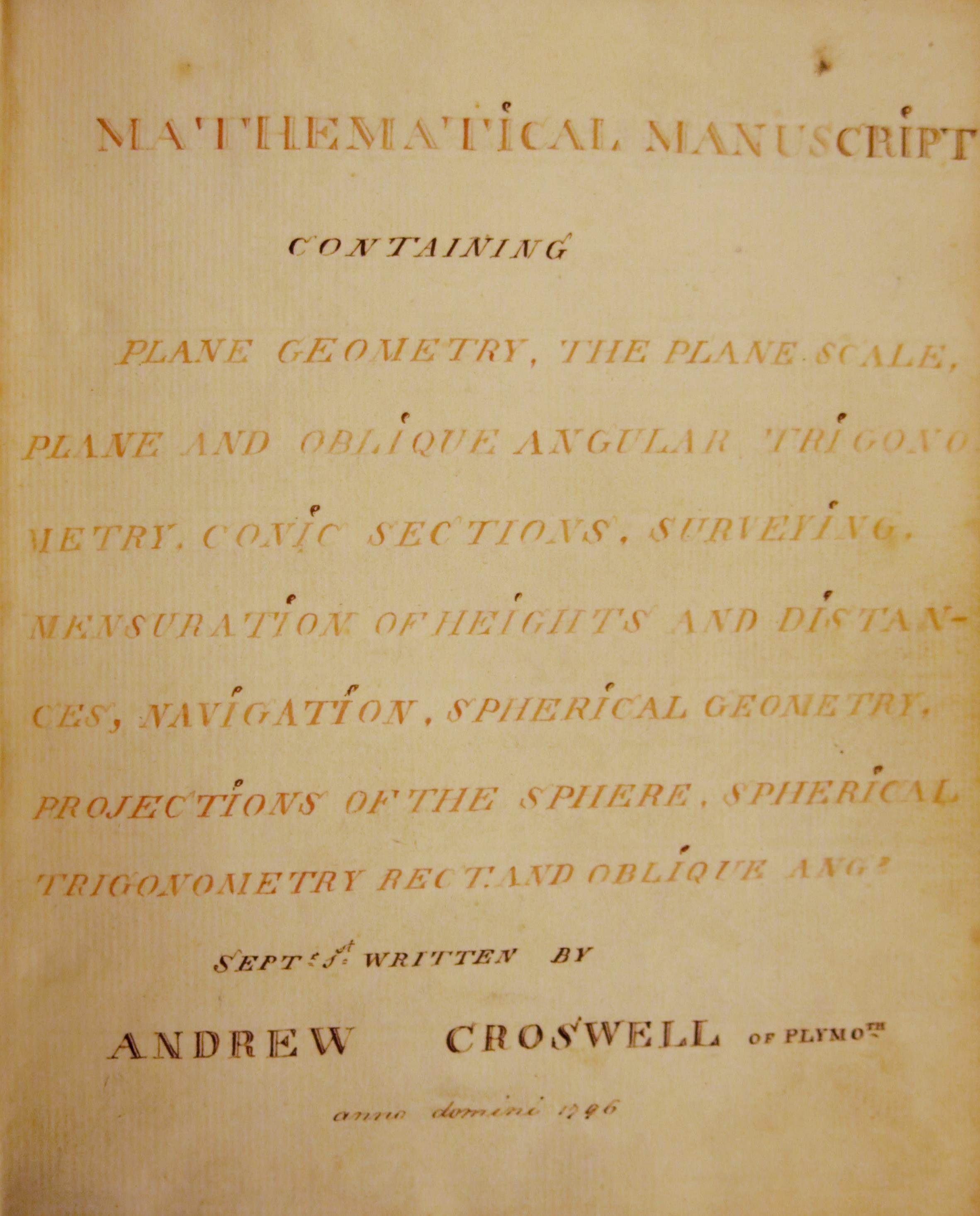

12 Feb. Saturday. Foggy & cold but went out to see Harry Lauder in the P.M. Very amusing.

Harry Lauder, source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Harry_Lauder_1922.jpg

13 Feb. Sunday – Sleeting. Walked & church. In the afternoon went to hear Italian band – delightful. Snowing & blowing.

14 Feb. Monday – Bitter cold but went out to hear Italian band again on the Pier. Crowds very amusing.

15 Feb. Tuesday not so cold & bright. Went to walk. In the P.M. to hear the Italians. Took our [word].

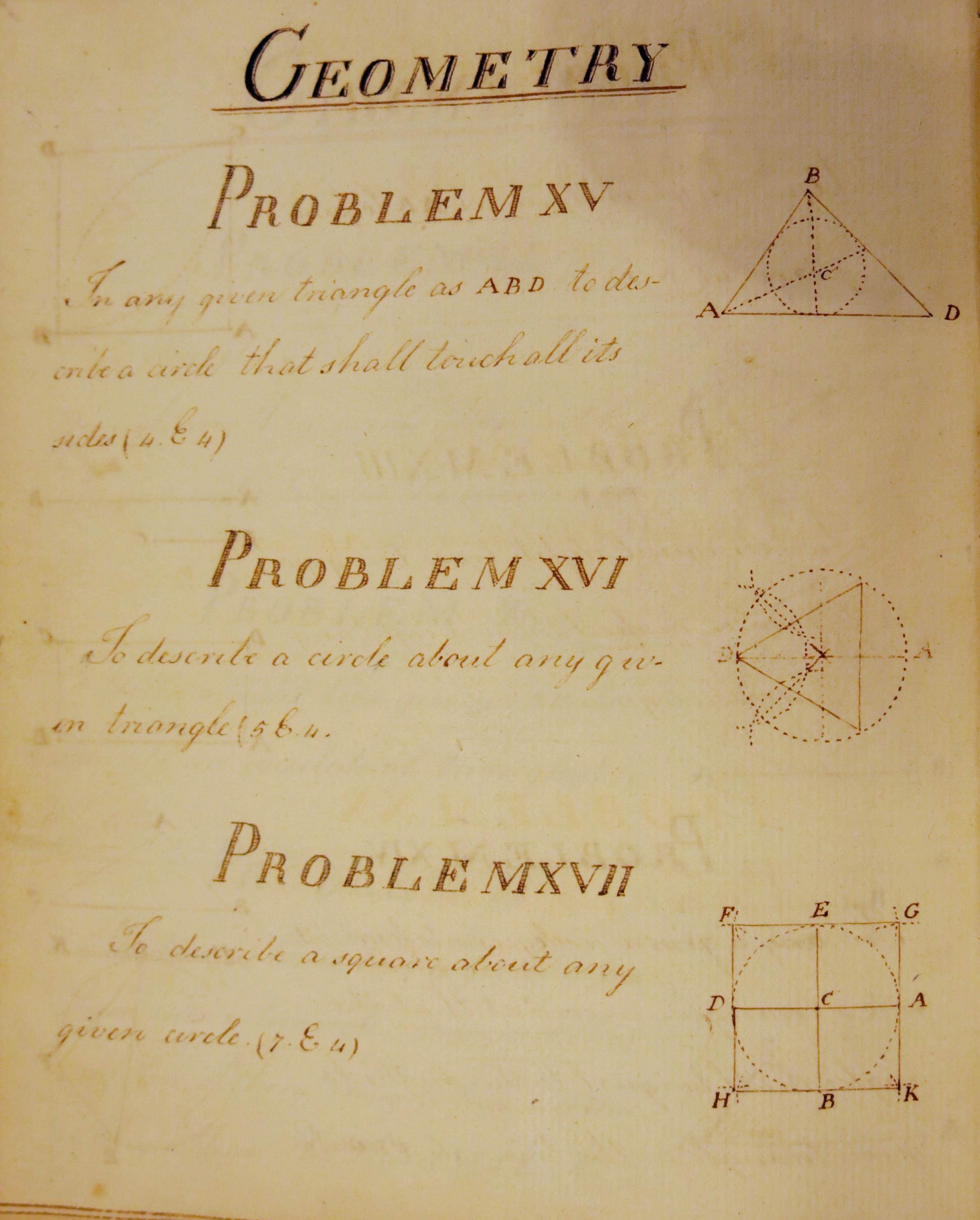

16 Feb. Wednesday. Lovely day & warmer. Walked to the Inlet & back on the beach. Went to hear Mrs. Pat Campbell in Pygmalion.

Mrs. Patrick Campbell / Beatrice Stella Tanner, source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mrs-patrick-campbell-2.jpg

17 Feb. Thursday – walked over four miles (same yesterday) & back on beach in the other direction. Last time to hear Italians.

18 Feb. Friday – Took last walk. Left at 2.30 – N.Y. at 5.40. Went to Belmont. Saw Mr. Moorfield Storey, Jack Peabody, Henry Harves, Bob Sbaros all going to Atlantic for holiday.

19 Feb. Saturday – Very cold & windy. Went to the new Colony Club & a few errands. Come home on 1ok. Feeling very well.

20 Feb. Sunday Church – to see Parmans. Lunched at H.G.C’s. Family to dine. Richard goes off this week.

21 Feb. [word]. Lunched at Marian’s. Went to Mrs. Fitz musical. Very cold but clear.

22 Feb Walked down to thee Charley Pierson with Marian. Drive out to see Mrs. Hodder. Lovely spring day.

23 Feb. Wednesday – Mrs. Ward’s lecture. Lunched at Club. Art Mus. lecture. Went to [word] at Higginsen’s.

24 Feb. Thursday – Lunch club here – fair. Went to call on Mrs. Wulhin. Dined out at C.S. Sargent’s big affair. CPC went with me.

25 Feb. Friday – Errands & Dr. Cockett. Splendid concert. Rainy & slippery.

26 Feb. Saturday – Mrs. Lysen’s reading. Raining hard & warmer. Went to [word] & hard no trouble. To concert again.

27 Feb. Sunday – Church. Lunched at H.G.C.’s Went to war lecture by Palmer at Mrs. N Thayer’s. Family dinner.

28 Feb. Monday – [word]. Lunched at Marian’s. Went out to Museum for botany lecture. Very interesting. Dined at South End H. Mr. Words took me in.

29 Feb. Tuesday – Ronlet reading in the morning. T. Club in the afternoon. Paid some calls.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original.