By Anna J. Clutterbuck Cook, Reader Services

Today, we return to the line-a-day diary of Margaret Russell. You can read previous installments here:

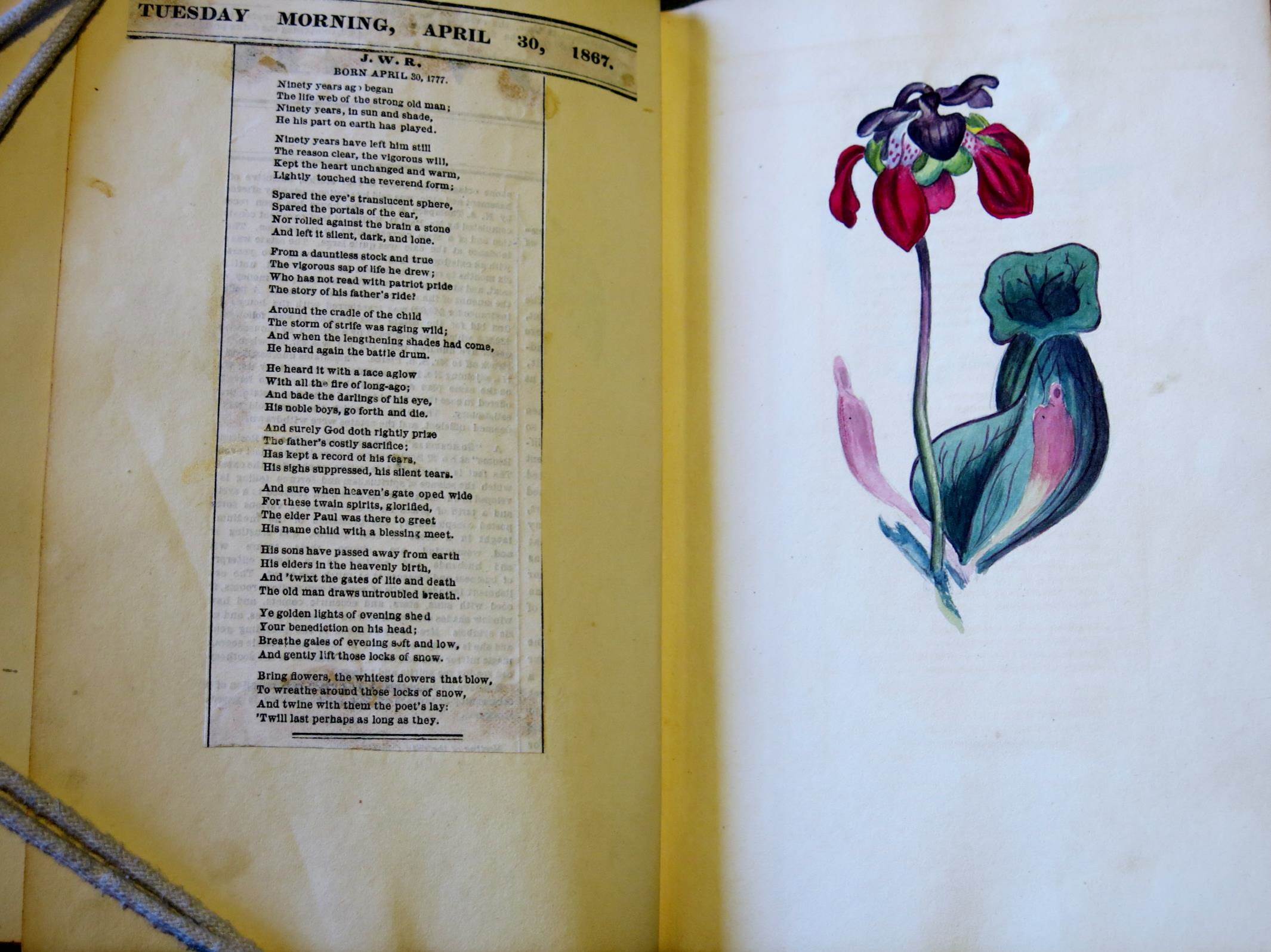

May.

June begins with the Russell household’s seasonal relocation from Boston’s Back Bay to Swampscott. Between 1870-1940, many prominent Bostonian families maintained summer estates north of the city. Dorothy M. Anderson, in her book The Era of the Summer Estates (Swampscott Historical Society, 1985), describes the preparations that took place before summer residents arrived:

“The unpredictable devastation of rugged winters and howling storms along the seacoast often necessitated considerable exterior house repair work such as roofing, shingling, chimney repair, and painting. Copper screening, subject to salt damage, often needed replacement. Also, wooden shutters had to be removed and stored, blinds opened, windows washed, and awnings obtained from storage and set in place. … Room after room, inch by inch, had to be treated appropriately to ensure total cleanliness and attractiveness before the ‘family’ arrived. …This ten-day to two-week indoor and outdoor undertaking using two and often several employees was crowned, as it were, by the arrival of the maids who set the bedding, china, linens, silver, and sundries in readiness. With a midweek arrival of the owner and spouse, the ‘family’ was ‘in residence’ for the season. And of course it was understood that, in many instances, the household would become two or three generations with the closing of schools and the onset of summer itself” (78).

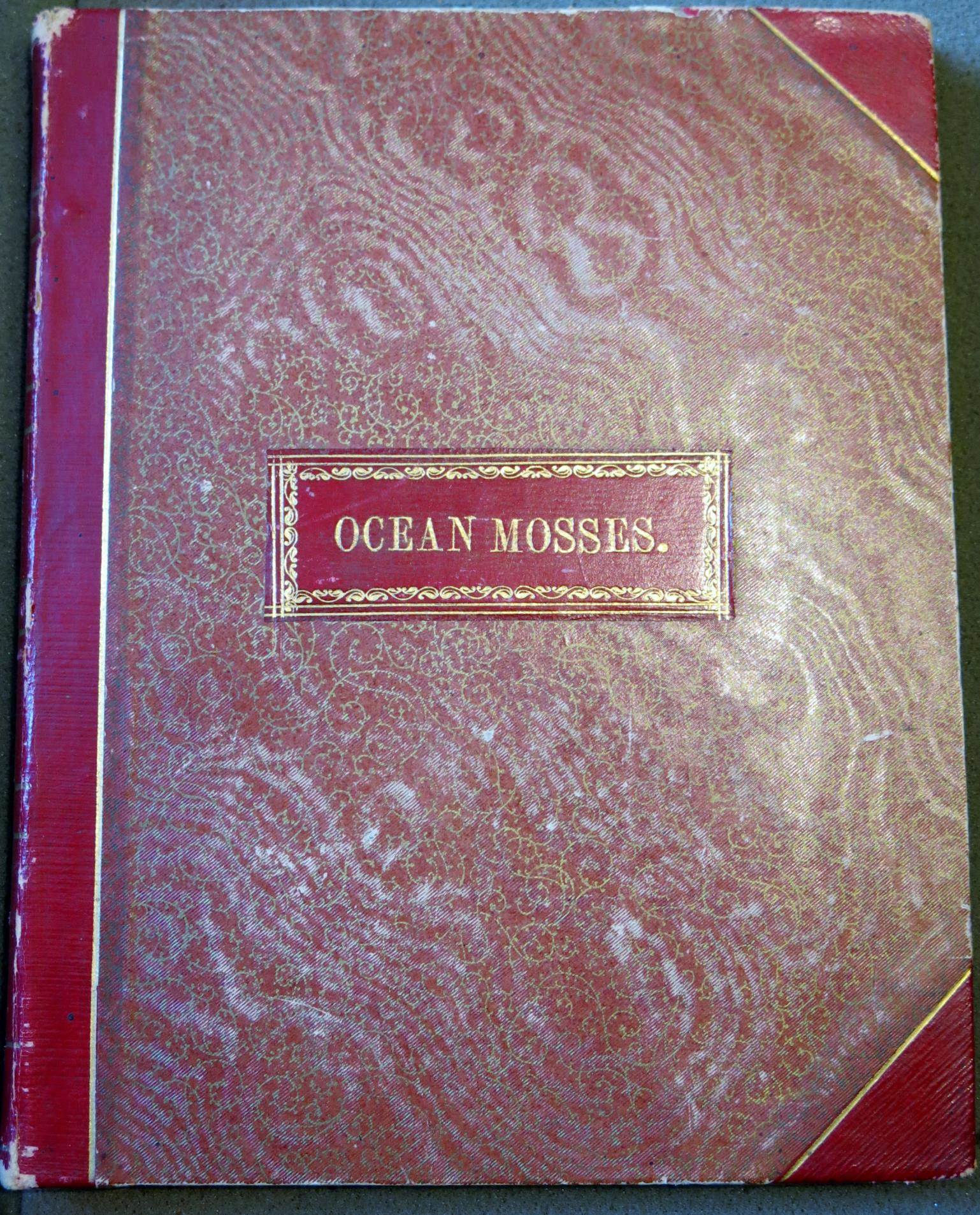

Margaret Russell oversaw the packing (see the end of May), remove, and unpacking as the household shifted, and these activities appear to have taken time and energy — though did not curtail her amateur botany, afternoon drives, and social appointments. On the 20th she packed once again and was on the train down to Asheville, North Carolina, to visit friends and enjoy the Blue Ridge Mountains. “Splendid view, azaleas wonderful.”

* * *

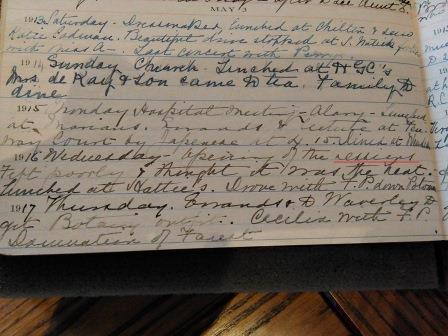

June 1916

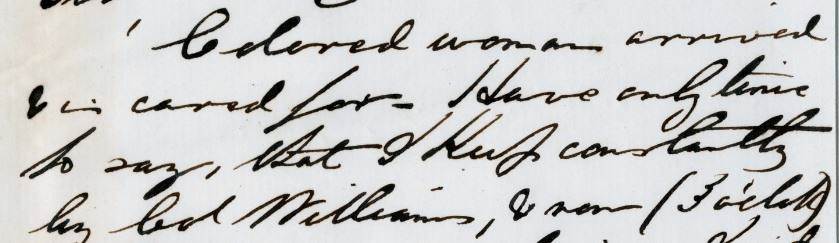

1 June. Had movers for move to Swampscott. Mama less tired than other years. Servants & [illegible] A.M. Me at 2.15.

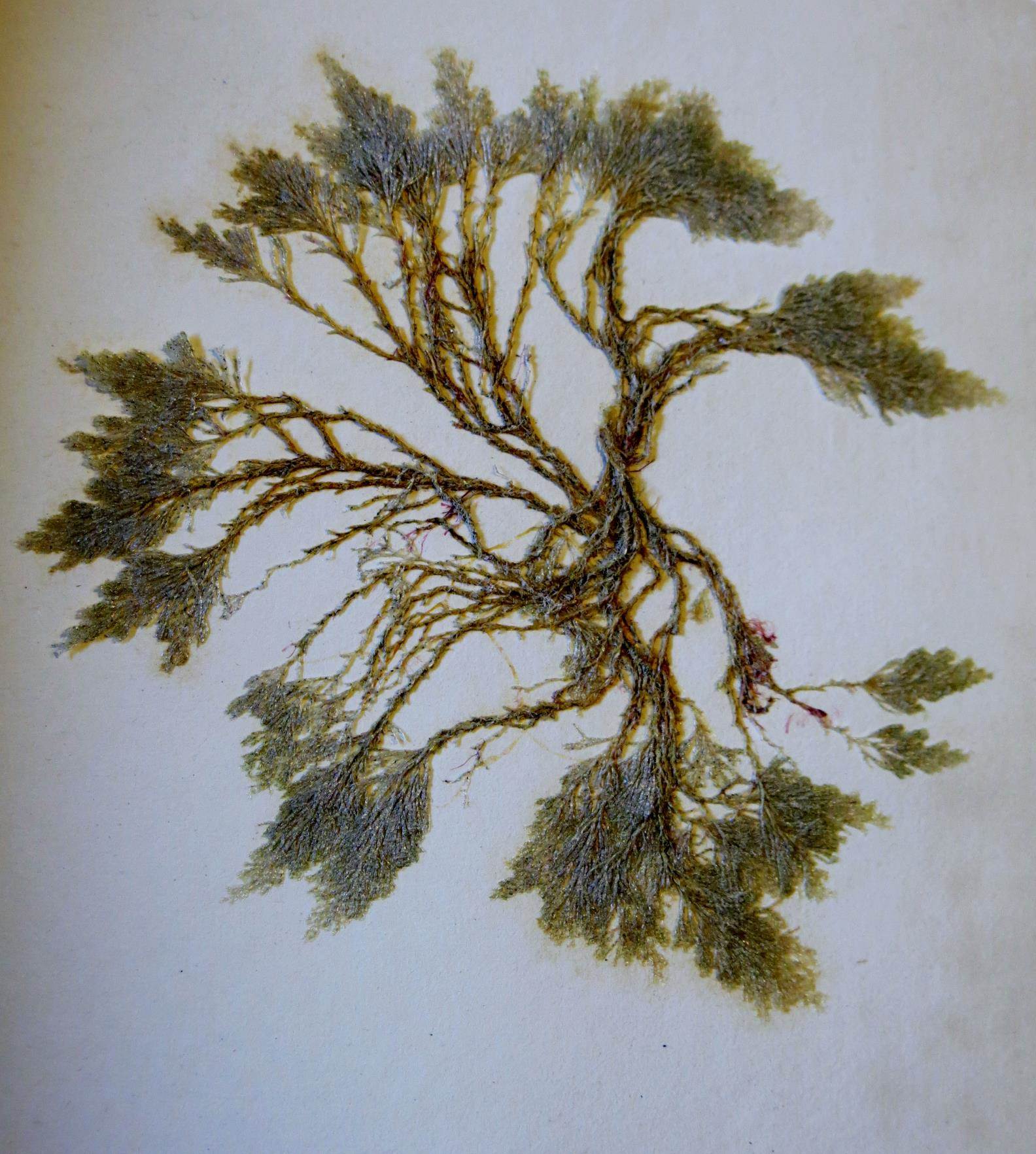

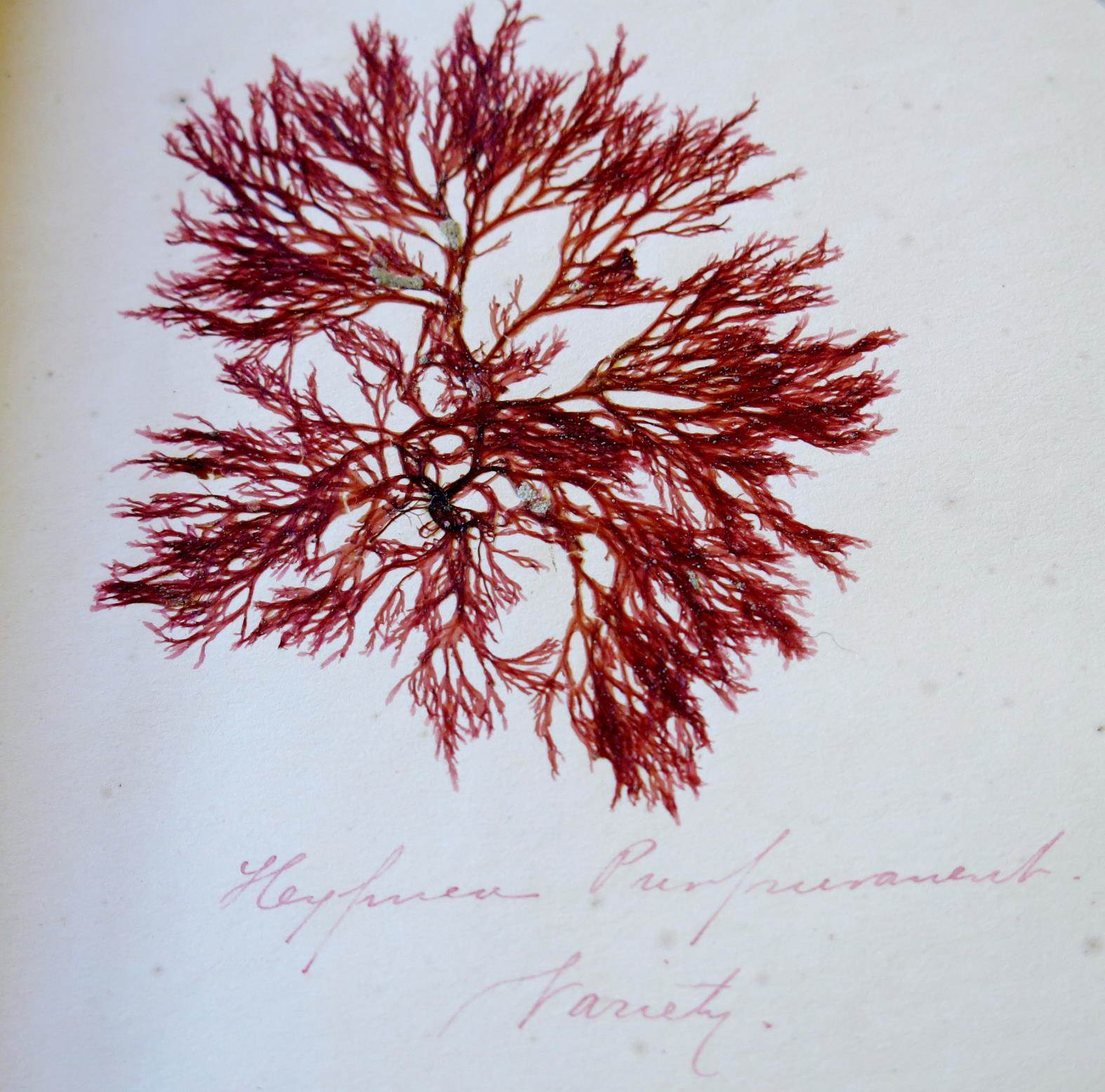

2 June. Friday. Unpacking. Went to Lynnfield bay & found Bug [illegible] in flower & to Marblehead for S. Stellata which was in flower.

3 June. Saturday – Went over & lunched with the H.G.C’s at Nahant. To salem for errands.

4 June. Sunday. Walked to church & back without fatigue.

5 June. Monday – to town for Hosp. meeting & errands. Lunched at Mariner.**

6 June. Tuesday. [illegible] in my room [illegible]. Moving. Lovely drive to Beverly & Hamilton.

7 June. Wednesday – Arranging my room. Took long drive to Beverly & Hamilton.

8 June. Thursday – To town for Chilton meeting – errands & to see Aunt Emma. Cold & Drizzling.

9 June. Friday – Raining & blowing very cold. To Lynn for errands. Rested after lunch & went to Nahant to see Mrs. L. Leukerman & the H.G.C’s.

10 June. Saturday – Pouring all day. Went to N. Andover to lunch at Mifflins. The H.G.C’s Mrs. James Lawrence.

11 June. Sunday – Cleaning – Walked to church & back P.M. Raining again.

12 June. Went to town for errands – Mary – last visit to Dr. S. Lunched at Mariner. Pouring again.

13 June. Tuesday – Sunny day. Walked to church & back. Went to see Charlie [illegible] & then to drive. Cold east wind.

14 June. Wednesday–

15 June. Thursday – Town all day – Hosp. to see Murray girl. To see Hattie Loring also.

16 June. Paper says this is the 9th day of rain. Baby went home. Paid calls at Nahant.

17 June. More rain than ever. Lunched at Nahant with H.G.C’s. Down to Marblehead to see Edith & the baby.

18 June. Walked to church. Family to dine – C gone to Canada for fishing.

19 June. Went to town for errands. Lunched at Mariner. Packing in P.M.

20 June. Packed & went to town. Had meeting of E[ar] & E[ye] comm. Then to take 1 o’c to N.Y. spent night at Belmont.

21 June. Wednesday – Took a walk & did a few errands. Lunched at Penn. station. Left at 1.08 for Asheville. Comfortable weather.

22 June. Arrived A– at twelve. After lunch rested & then took walk up in the woods. Lovely as ever here.

23 June. Friday – Walked up to see the Howington’s [illegible]. All so glad to see us & we them. Stayed on piazza P.M. Looked showery.

24 June. Saturday – Took all day trip in motor with lunch for Mt. Pisgah. Splendid view, azaleas wonderful. Thunder storm & bad roads coming home.

25 June. Sunday – went to St. Mary’s. In P.M. drove to Mountain Meadows. Organ concert in the evening. Lovely weather.

26 June. Monday – I stayed home and Miss A– went to see Howingtons. P.M. drove to Swann[illegible] valley. Moving pictures every evening.

27 June. Tuesday – All day trip in motor to Hickory Nut Gap. Saw fox & cub. P.M. visiting & then another lovely walk.

28 June. Wednesday – Stayed at home in A.M. Miss Holman arrived about two. Drive her to see Miss H’s eyes. She seems to enjoy seeing the hotel & people.

29 June. Miss H– left after breakfast. Miss A went again to see Mrs. H– & I packed. Hot. Left at 2.35 it soon cooled off.

30 June. Arrived in N.Y. hours late so lost our train. Crowds so great that could get no seats. Took 4 o’c & at New Haven got into parlor car. Home about 11.30.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original.

**In previous installments of the diary I have transcribed this word as “Marian’s” but in this instance the word looked unmistakably like “Mariner” and I have adjusted my transcription accordingly throughout this entry.