By Shelby Wolfe, Reader Services

When friends and family ask me what they should do while visiting the Boston area in the fall, I generally get a strange look after my main recommendation. I tell them to visit Mount Auburn Cemetery, the first landscaped “rural” cemetery in the United States, located between Cambridge and Watertown. It’s a beautiful setting year-round, but there’s something about this season that brings out the best in Mount Auburn.

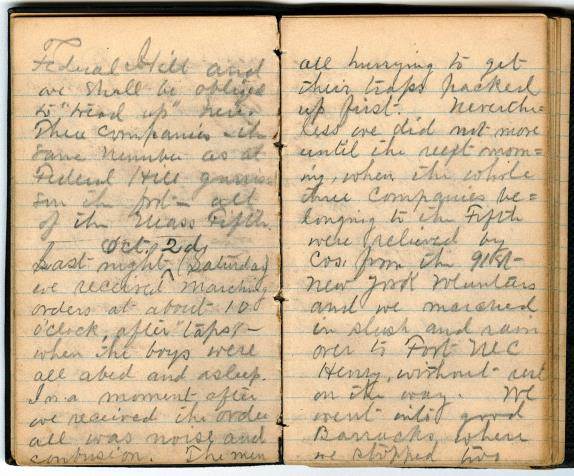

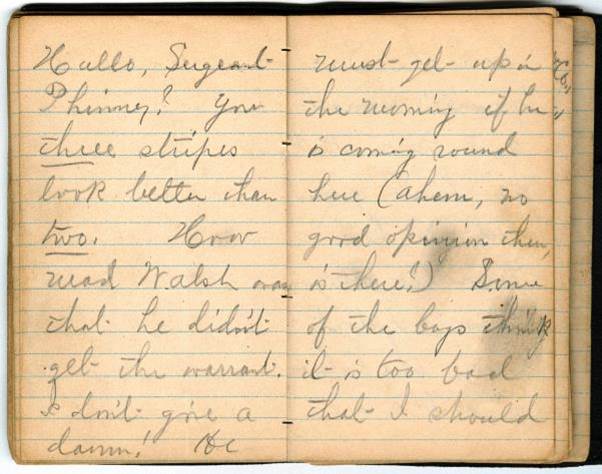

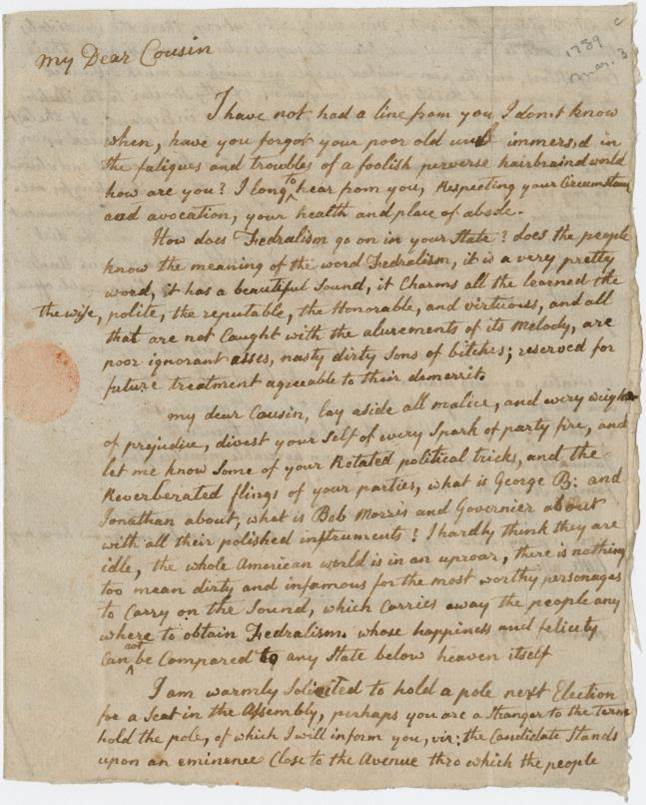

I’m tempted to list all of the reasons why I love Mount Auburn, but I’ll resist that urge here and tell you what I found out about it while searching our online catalog, ABIGAIL – mainly, that the MHS collections contain a lot more on Mount Auburn than I previously thought. Much of what we have are published materials, including catalogues of proprietors, maps, guides, pocket companions, and anthologies. Then, there are more personal items, such as poems written about Mount Auburn, speeches given at the cemetery, admission tickets, a broadside depicting Mount Auburn “on a delightful day in the Autumn of 1876,” and more. Mention of Mount Auburn arises in manuscript collections as well. Search for yourself in ABIGAIL to see what kinds of materials you can find at the MHS connected to this historic cemetery.

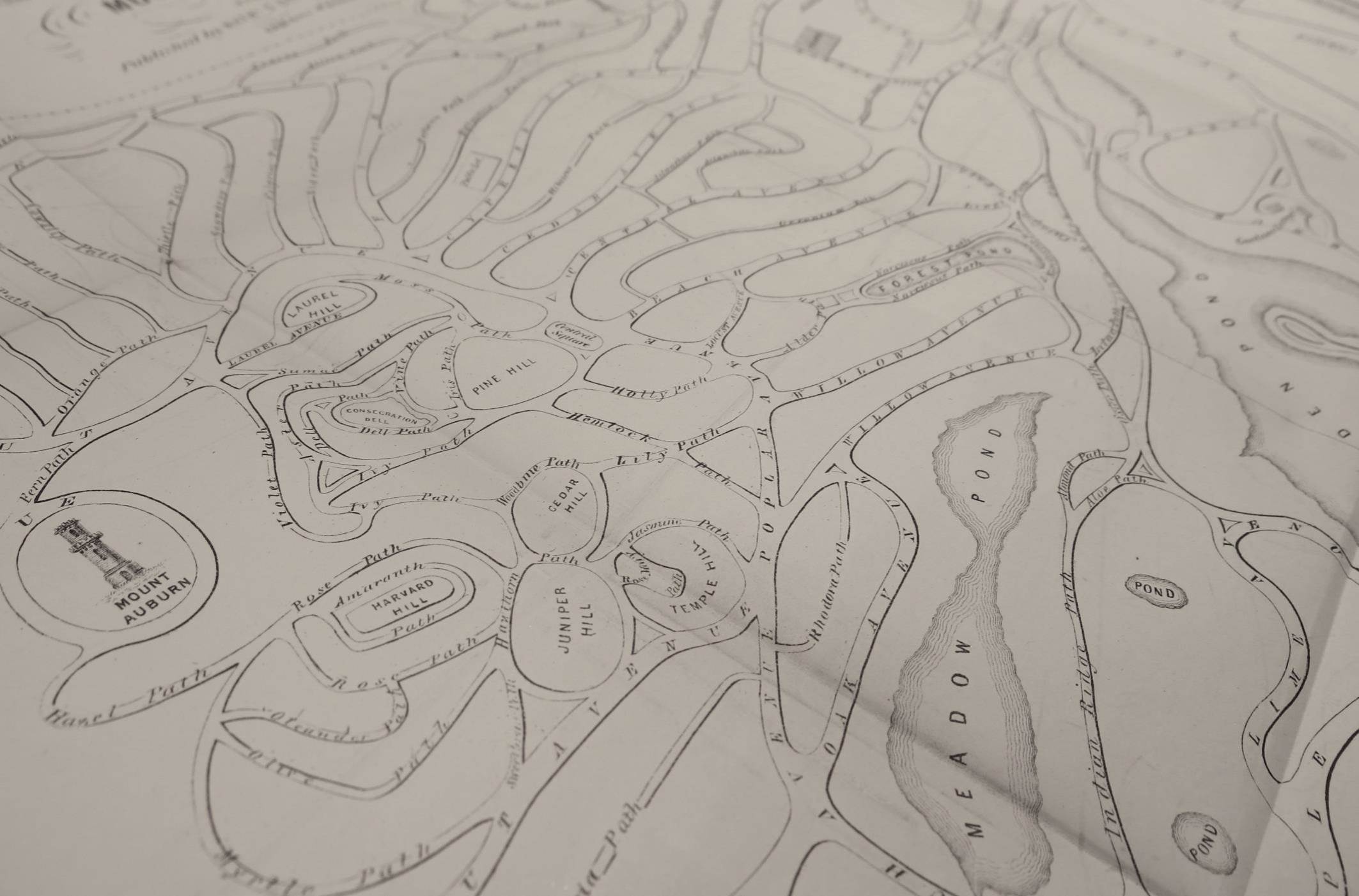

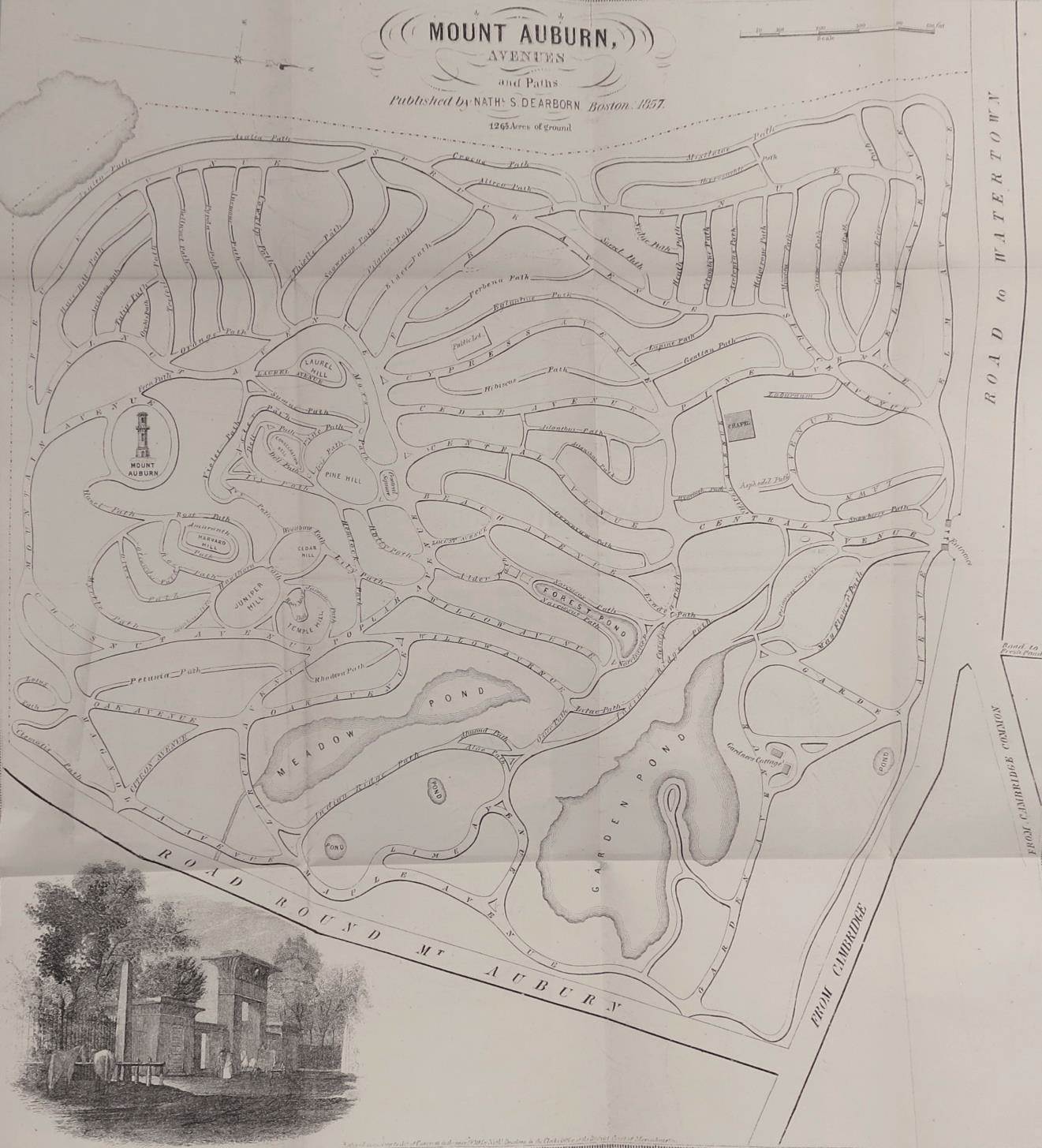

For someone whose interest in maps almost rivals her love of cemeteries, I found the fold-out maps in our copies of Dearborn’s Guide through Mount Auburn, published by Boston-based engraver Nathaniel S. Dearborn, most interesting. The map in the 1857 edition includes small engravings of the Egyptian Revival entrance and Washington Tower, an observation lookout providing panoramic views of Cambridge, Boston, and beyond. The guide in general is full of useful information about the cemetery as it functioned in 1857. Regulations include prohibition of “discharging firearms in the Cemetery,” and a warning of prosecution for anyone “found in possession of flowers or shrubs, within the grounds or before leaving them.” On that note, a poem titled “Touch Not the Flowers” by Mrs. C. W. Hunt adds a lyrical emphasis to the rule (and implores visitors with the ominous last line, “Touch not the flowers. They are the dead’s.”). After all, the cemetery was and remains as much a horticultural gem as a place of burial and memorial.

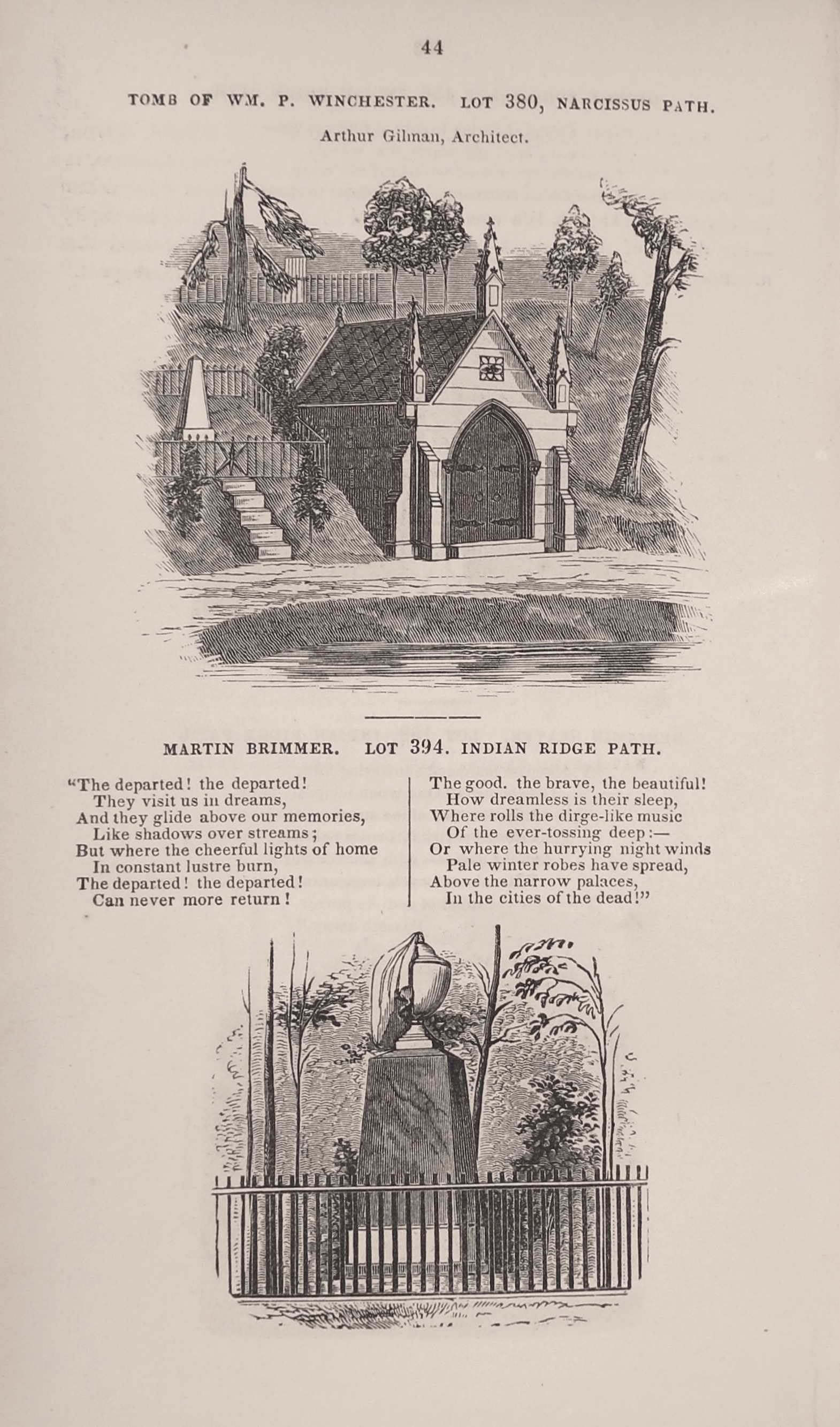

Among the conditions for proprietors, plot owners are informed that any monument, effigy, or inscription determined to be “offensive or improper” is subject to removal by the Trustees. Engraved illustrations present the cemetery-goer with a sampling of must-see monuments of notable men and women (and pets), including a memorial to Robert Gould Shaw, the impressive tomb of William P. Winchester on Narcissus Path, and a marble sculpture depicting the watchdog of Thomas H. Perkins, “an apparent guard to the remains of the family who were his friends.” Beautiful illustrations of the tower and chapel embellish the guide as well.

For the directionally gifted, the guide lists names of foot paths, avenues, and carriage roads, with rather complicated descriptions of how they are situated – “Willow, with two branches, the 1st branch from Poplar Av., northeasterly. to Narcissus Path, then curving easterly for the 2nd branch, to the south, to Larch Avenue.” I think you can see why Dearborn included a map.

Visitors can find up-to-date maps at the cemetery entrance today, so grab one for yourself and venture among the monuments and mausolea. Then, visit the library to see how the cemetery has changed over the years!

Mount Auburn Cemetery (Cambridge, Mass.)

Mount Auburn Cemetery (Cambridge, Mass.) Maps

Mount Auburn Cemetery (Cambridge, Mass.) Pictorial works.

Mount Auburn Cemetery (Cambridge, Mass.) Poetry.