By Christina Carrick, Publications

Serving in his official role before the Superior Judicial Court for Suffolk County in August 1780, Atty. Gen. Robert Treat Paine prosecuted a complicated wartime case. On the docket was murder; at stake was legal precedent in a new nation. In the midst of the Revolutionary War, Paine had to confront a challenging question: should enemy combatants—or prisoners of war, in this case—be treated and tried as citizens of the country? Or should they be removed into the jurisdiction of independent military courts, subject to separate laws and rights?

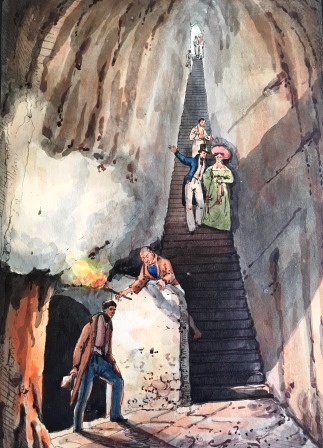

In this particular situation, the homicide charge arose from a conflict between British prisoners incarcerated on a ship in Boston Harbor and the American servicemen guarding them; the conflict expanded when more Americans approached the ship to discover what was wrong. That night, August 10, Maj. John Rice took a small boat from Boston to investigate a reported riot on the prison ship. A British prisoner with a gun and bayonet leaned over the rail as Rice’s boat pulled alongside. The armed man “dam’d” Rice and “swore he wd. blow [his] brains out.” Rice quickly saw that he should take the bayonet-wielding prisoner at his word. The ship’s guards had been disarmed, and one, Sgt. Thomas Beckford, lay dead from a gunshot to the neck.

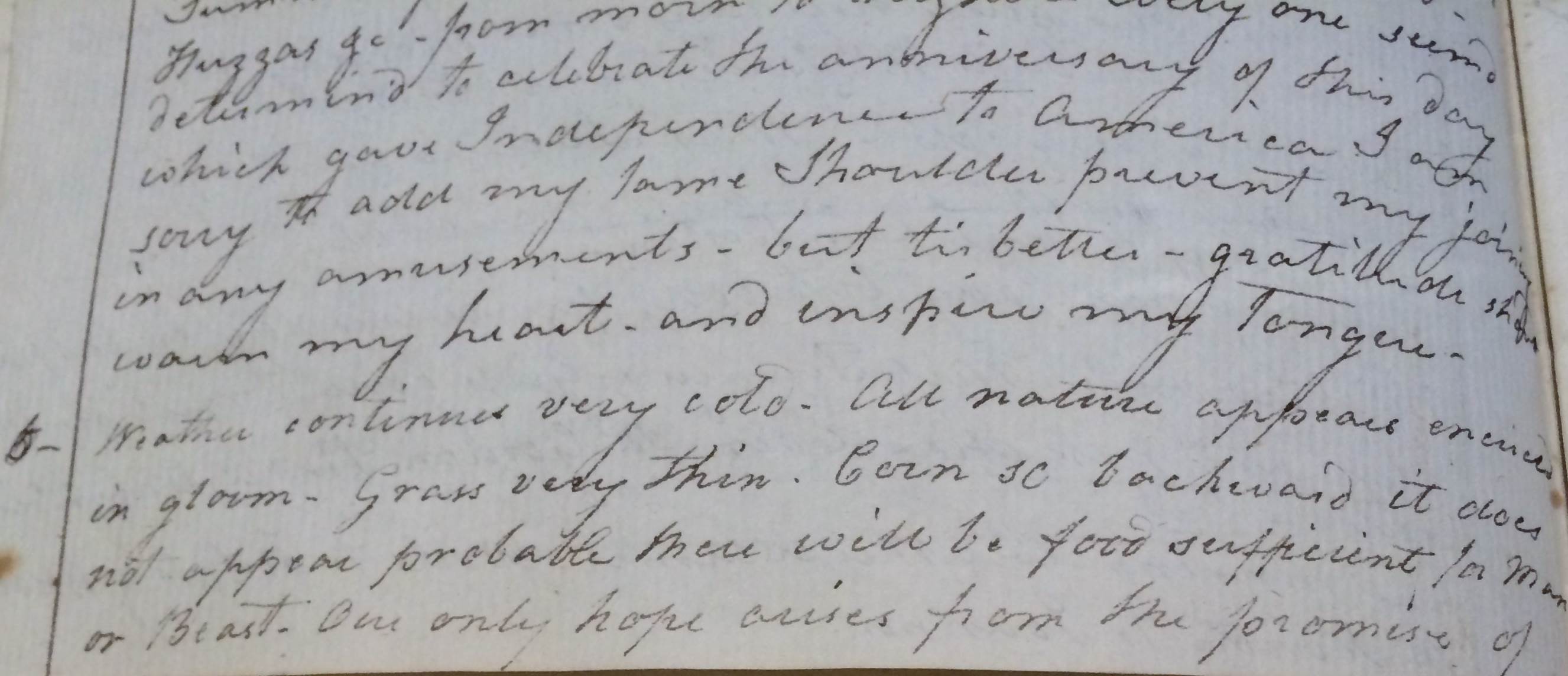

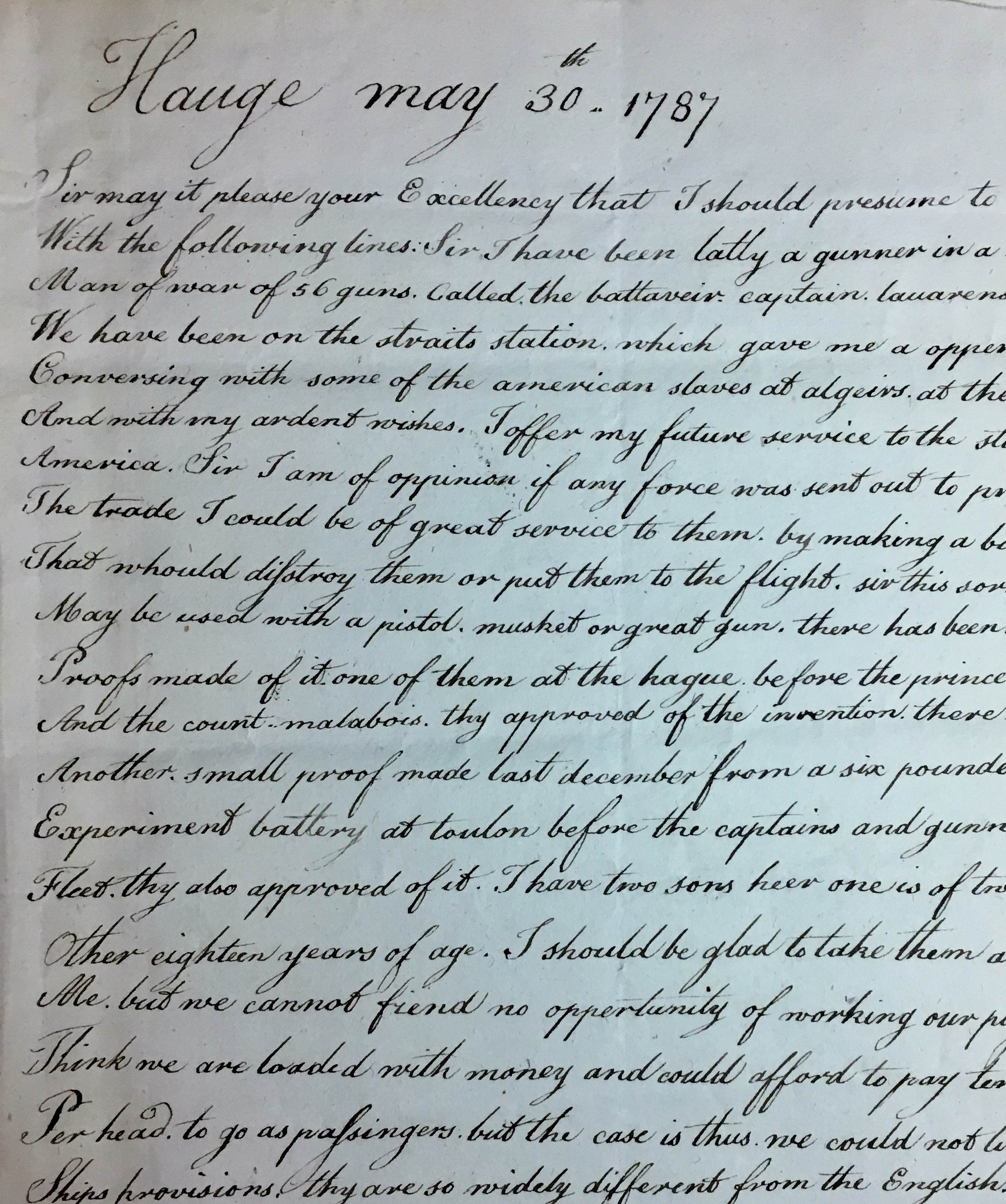

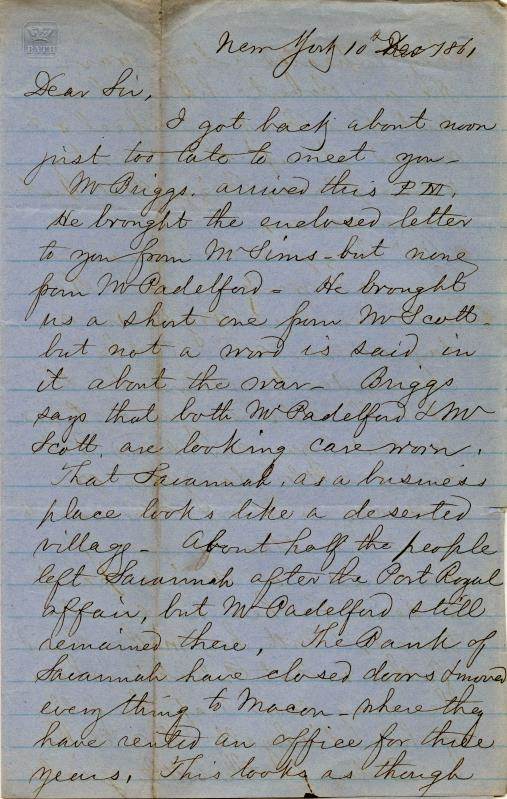

Lt. Isaac Morton later gave a detailed account of the incident:

I was Lieut. & officer of the day. I heard a gun fired on board the Prison ship just before sun down I went along side heard a disturbance on board. Serjt. said the centry was disarmed; I askd the Pris: how they fared, they sd. the Guard had not abused them Thos. Lynch damd me for a Rebel & if I came to the assistance of the Guard I was no better than they & he would throw me over board: McGregor sd. you are not better than the guard you Yankey Rogue, & struck me on the head with his fists. Michael Hay said you shall not abuse him McGregor came with Gun & Bayonet & threatned to run me through, & threatned me to throw me over board & all of us; McGregor said he brought his Gun from Ireland, he said he disarm’d the Guards to make an Escape: Major Rice came along side, & bid me step into the boat. McGregor having a Gun in his hand sd. if you offer to go into the boat Ill blow your brains out, there was a cry of fire fire blow their brains of the damd Rebell out Major Rice bid us shove off, they cryed on board the ship fire blow their Damd brains out & immediately they fired & a man dropt, a billet of wood then from the ships knock’d me over board

Paine’s notes on Lt. Isaac Morton’s testimony before the Superior Judicial Court

The ship ran aground near shore and multiple boats from Boston quickly suppressed the uprising. The rioting prisoners were moved from the prison ship into the city jail, where they awaited trial.

In terms of evidence, the case was straightforward: Major Rice and several guards from the ship had witnessed the riot. It was not completely clear who had fired the shot that killed Beckford, but the rioters were consistently named from testimony to testimony. The fundamental legal question was not who had fired the killing shot but whether prisoners of war should be tried in civilian court at all.

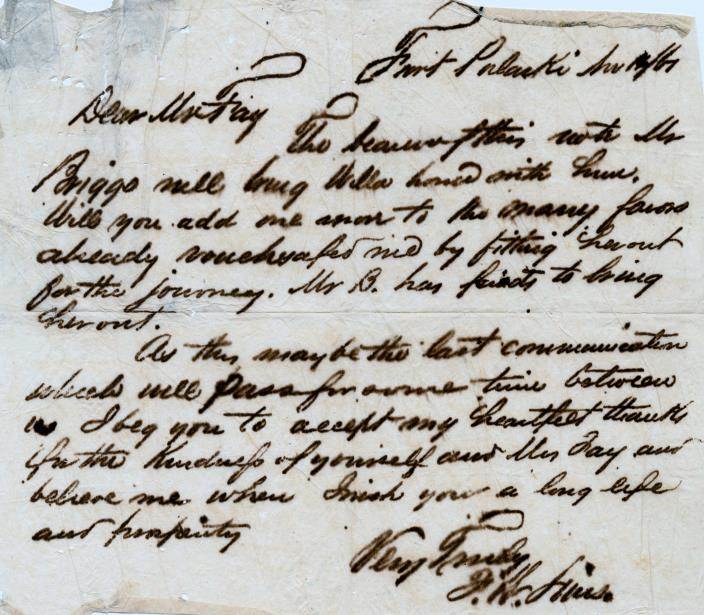

The nine defendants sent a petition to the court, claiming that they did not lie within its jurisdiction. They argued that they “ought not to be compelled to answer to sd. Indictment” because

Homicides & other offences committed by the Subjects of one State against the Government & People of another State while an open War is subsisting between them, ever have & of right ever ought to be enquired of heard & determined by the Courts Martial in the Country or place where such Homicide or Offences may be committed, agreeable to the laws of Nations & the laws of War *

In this, they insisted they should be tried in a court martial and not by “municipal laws, Customs & statutes” as American residents.

Despite their petition, the case went to trial. Paine, as attorney general, made the commonwealth’s case for prosecution. Increase Sumner, a Boston lawyer and future Massachusetts governor, argued for the defense. Sumner tried to convince the jury that since the defendants “were Prisoners by force they had right to regain their liberty by force.” This addressed another central question that hung over the proceedings: when did enemy combatants lose the rules-of-war right to act combatively? Did they have a legal or natural right to revolt against their imprisonment? These questions would not be clearly answered during the trial, but Paine scoured his legal texts to find precedent.

Paine’s notes from the case included references to many of the major legal texts of his time: Vattel’s The Law of Nations, Coke’s Reports, Hale’s Historia placitorum coronae (History of the Pleas of the Crown), and Blackstone’s Commentaries, among others. He noted from Vattel that “the right of war gives right to kill whenever they can” and from Blackstone that “an Alien Enemy is intitaled to no protection.” Nonetheless, he asked himself if it would “be murder if Congress should order all the Prisoners to be hung up at the Yard arm.”

Ultimately, the jury declared the defendants not guilty. The prisoners fade into the historical record, and it is not clear how they fared for the remainder of their captivity. The case, however, would later be cited as a supplement in the state’s Supreme Judicial Court reports, and the questions raised about the legal status of enemy combatants continued to plague the nation throughout its growing pains.

For the full trial story and Paine’s other legal endeavors, check out the Robert Treat Paine Papers collection at MHS and the published Papers of Robert Treat Paine. The Massachusetts State Judicial Archives also holds records on this case, including the above petition. Paine’s notes for this case will be printed in full in volume 4 of the Papers, forthcoming from the MHS Publications Department in 2017 thanks to a generous grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC).

*Massachusetts Judicial Archives Suffolk Files 102707, quoted with permission from the Massachusetts State Archives.