By Rakashi Chand, Reader Services

Unlike any other historical figure, Benedict Arnold’s contributions to the Patriotic Cause were so great that, had he not committed treason, history might have depicted him as a Founding Father. His accomplishments cannot be negated, his leadership and skill as a solider were unsurpassed, and his men loved him; had he been a less admired man, perhaps his treachery would have been less painful. The hero of the Battle of Saratoga, Arnold’s military success came at high costs, his war wounds leaving him lame and requiring the use of a cane throughout his life. Arnold fought courageously and boldly on the battlefield, the ‘Warrior’ of the Continental army, he was greatly admired and respected by his troops. So why would a man of such heroism resort to treason?

Well, perhaps it had to do with his passionate heart.

In late 1776, George Washington sent Arnold to Providence to take control of poorly defended Rhode Island following the British takeover of Newport. “His presence will be of infinite service,” Washington wrote, and indeed the 4,000-man Rhode Island militia was excited to hear of Arnold’s arrival. Arnold soon found they were not equipped for an attack on British forces and, with the lull of winter upon them, he went north to Boston in hopes of raising more troops. It was here in Boston that the middle-aged, widowed, weathered Arnold found himself embraced by Boston’s high society, including the remaining loyalists.

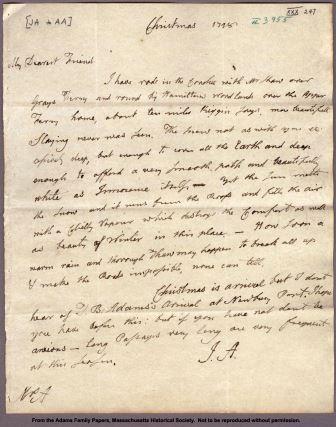

After the evacuation of Boston, some loyalist families returned to the city to look after property interests. One such family included Mrs. Gilbert DeBlois and her 16 year-old daughter, Elizabeth “Betsy” DeBlois. Arnold, who recently lost his wife, encountered the loquacious, flirtatious, and charming young Betsy through mutual acquaintances, namely, Lucy Flucker Knox, wife of General Henry Knox and daughter of Thomas Flucker, the royal secretary of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Arnold promptly fell passionately in love with Betsy and tried desperately to court the girl, but her mother had already chosen another suitor, an apothecary’s apprentice. This did not stop Arnold from pursuing her; enlisting the help of Mrs. Knox, he secretly sent gifts and love letters. Arnold even sent a ring, said to be an engagement ring.

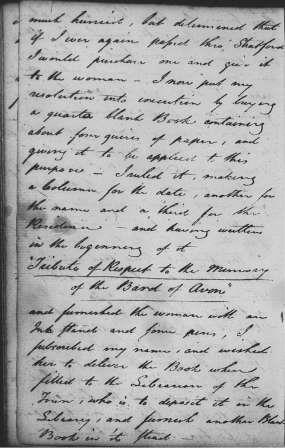

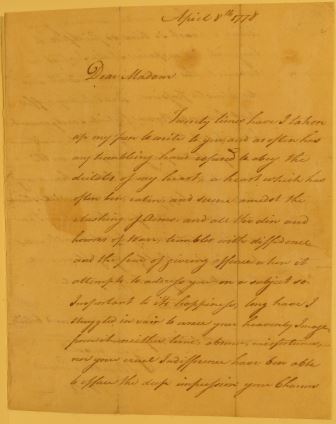

Here at the MHS is one such letter from Arnold to young Betsy. This gushing missive, meant to sweep the young belle off her feet, is the archetypal ‘love letter’. In fact, I would suggest that those who do not enjoy romance should perhaps abstain from reading any further…*

April 8th 1778

Dear Madam,

Twenty times have I taken up my pen to write to you, and as often has my trembling hand refused to obey the dictates of my heart, a heart which has often been calm, and serene amidst the clashing of Arms and all the din and horrors of War, trembles with diffidence and fear at giving offence when it attempts to address you on a subject so important to its happiness, long have I struggled in vain to errace your heavenly Image from it, neither time, absence, misfortunes, nor your cruel Indifference have been able to efface the deep impressions your Charms have made, and will you doom a heart so true, so faithful, to languish in despair; shall I expect no returns to the most sincere, ardent, and disinterested passion; Dear Betsy suffer that heavenly Bosom (which surely cannot know itself the cause of misfortune without a sympathetic pang) to expand with friendship at least; and let me know my Fate, if a happy one no Man will strive more to deserve it, if on the contrary I am doom’d to despair my latest breath will be to implore the blessing of Heaven on the Idol, [the] only wish of my soul.

Adieu

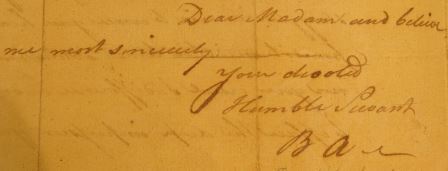

Dear Madam and believe

me most sincerely

Your devoted

Humble Servant

B A

In addition to this letter, the MHS also holds the ring that Arnold sent to young Betsy in the hope of attaining her hand.

I had read of the romances of Benedict Arnold before, but I never realized how much passion coursed through his words (and his actions) until I saw the actual love letter. Sadly, “Heavenly Miss DeBlois” refused Arnold and his gifts.

This devastating blow to the heart was received with an equally devastating blow to his pride from Congress. At the time, Arnold was due to be promoted in the ranks. Instead, Congress promoted five Brigadier Generals to Major General, all inferior to Arnold. Many, including Washington, were outraged and assumed Arnold would certainly resign at such an insult. Perhaps this prompted Arnold to begin questioning himself and the world around him…

What a romantic Arnold must have been! It seems he was passionate in all aspects of life, but one who fell zealously and fervently in love, although, all too easily!

A year later Benedict Arnold met Peggy (Margaret) Shippen, and his heart was aflame once again. He also wrote Peggy love letters quite similar to the ones he had sent to Betsy. (Well, no point wasting good prose.) Be still my heart, for Arnold strikes again!

…And then he turned out to be a traitor.

An early Happy Valentine’s Day to all the romantics out there, especially those who love historical romance!

*Please note that the transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the letter in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original.