By Susan Martin, Collection Services

This is the third post in a series about the wartime experience of Charles Cornish Pearson. Go back and read Part I and Part II for the full story.

*****

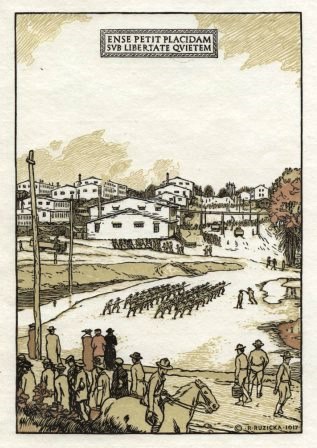

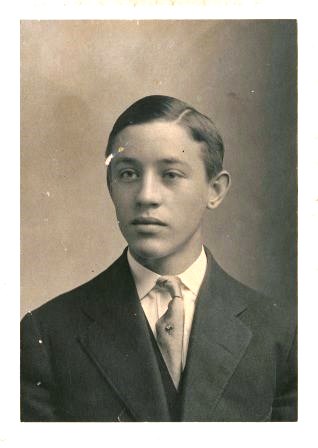

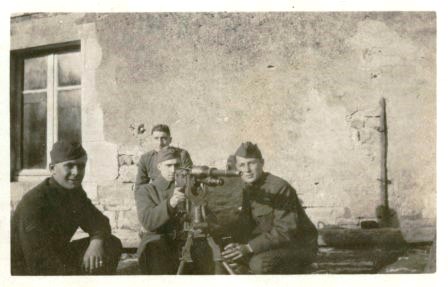

Today we return to the letters of Charles Cornish Pearson, a young man who served during World War I with the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, 26th Division, American Expeditionary Forces. If you want to catch up on the story, see Part I and Part II.

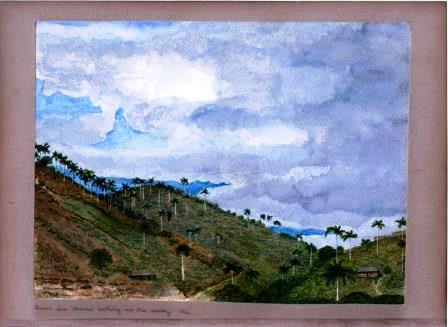

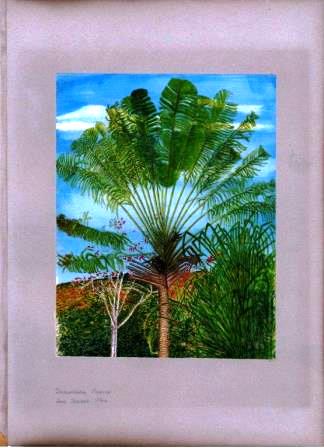

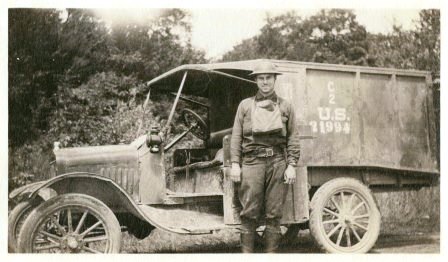

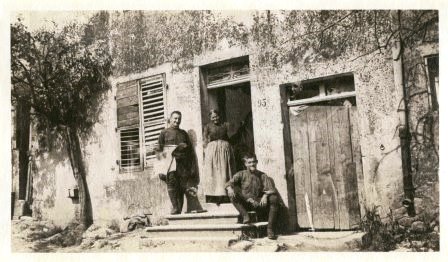

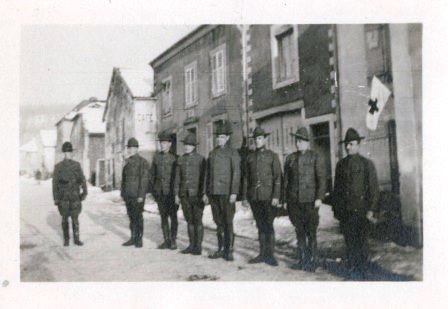

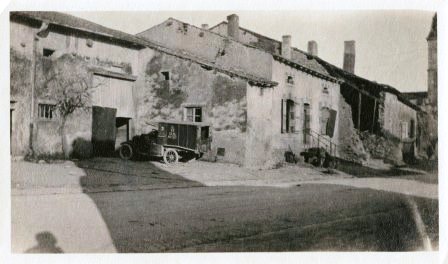

When we left him, Charles had been a soldier for about nine months and had seen his first direct fighting in the trenches of France’s Chemin des Dames sector. On 18 March 1918, his battalion pulled up stakes and began the two-week journey via train and automobile southeast to the Toul sector. The weather was beautiful, the country picturesque, and the troops enjoyed the welcome respite. This part of France was mostly untouched by the war. Charles wrote to his mother en route and described a typical French village.

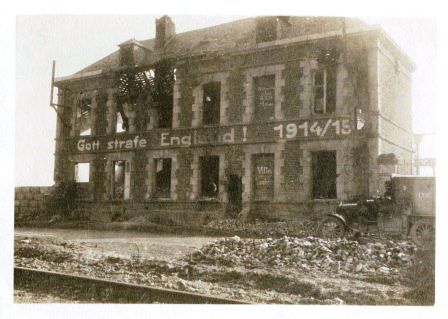

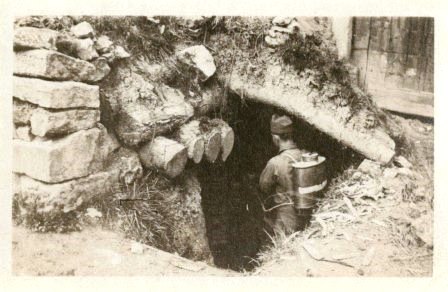

It is all very peaceful and so different from what we have experienced lately. Here War seems to have affected the village in the lack of men, hardly any being about except those past the age limit, and of course there are a few deserted houses and the others not kept up quite as well as in peace times I imagine. Picture on the other hand a village without any civilian population not a habitable house & even the church in ruins, with the military forces quartered in dugouts or cellars of the ruins of the old houses. It is an awful contrast I can tell you, still you quickly get hardened to it all, and take it all as part of the days work.

The 101st arrived at their destination on 1 April 1918, and Charles’ platoon was stationed at Mandres-aux-Quatre-Tours. He was promoted from corporal to sergeant that same day. The following day, coincidentally, was his 28th birthday.

Charles’ letters, originally chatty and carefree, had become a little more subdued as he experienced the realities of war first-hand. He described bursts of chaotic activity followed by periods of anxious waiting and uncertainty. The battalion never knew when it might be called into action at a moment’s notice. Meanwhile, regular gas alarms and barrages of shells frayed everyone’s nerves. (“They usually tune up about night fall,” Charles wrote to his sister, “so as to disturb our sleep I guess. These Boche certainly have a mean disposition that way, but suppose our gunners treat them the same way.”) Charles also told harrowing stories—for example, the day his detail dragged two dead mules and a wagon out of an exposed road, narrowly avoiding the German bombs dropped on the spot immediately after. All this kept him keyed up most of the time, he admitted.

Philip S. Wainwright, in his History of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, confirms that Charles’ platoon at Mandres “had its share of shelling every night.” (p. 33) Of course, Charles described things to his parents is his usual wry, understated way.

Up to the present time cann’t [sic] say that it has been especially tranquil. However we have gotten over the newness of it now and can listen to a big gun without shaking too much. […] Even at the present writing the Boche are sending a few shells over, but way over so don’t have to worry much. Funny how you can get to tell pretty well if they are coming near you by their whistle. At times that whistle gets on ones nerves but you can usually figure they are trying to locate a battery and not worrying about small fry such as yours truly.

April 19 was his parents’ anniversary, and he sent a telegram to mark the occasion. The following day, in the early morning hours, the Germans launched a surprise attack, and Charles found himself right in the middle of the Battle of Seicheprey. It was the largest American battle up to that point and certainly the worst fighting Charles had seen, but the Americans (mostly Connecticut men) held their own against the larger and more experienced German army and forced “the Hun” back.

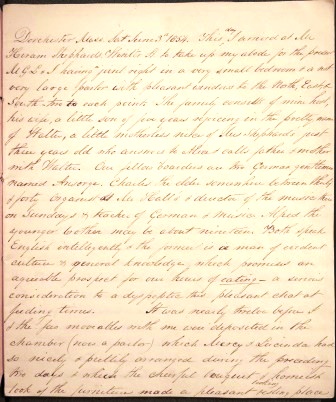

According to Wainwright, “During the intense bombardment of high explosive and gas which preceded the attack,” Charles’ platoon “suffered the first real casualties that occurred in the Battalion.” (p. 34) The first man of the 101st to be killed was Private Giuseppe “Joe” Molinari. Charles wrote to his parents in the aftermath of the battle and, without going into detail, called the past hours “H–l rippers” and “heartbreakers.” After his platoon was relieved, he reflected on his recent experiences in a letter to his brother.

We are supposed to be trained soldiers now so we get our full share of excitement that is going on. It sure is a plenty I can tell you. No use describing things over here as it [is] beyond my power any way. You have a nice explosive gas shell land in the story over your head during a general bombardment in the night and you have to get up half asleep & put on a gas mask and then wonder what your chances are of making a dugout. Take a hike up a road that is called Dead Mans Curve and pull a couple of dead mules off the road and with your detail grab hold of the wagon & pull it back for about ½ mile so it wont impede traffic, wondering all the time when they will harass the road again. You can write these things down but the reader doesn’t get any idea of what one is thinking of when said things are happening.

To his parents that same day, he wrote a letter just two pages long, closing with: “Don’t feel much in the mood for letter writing today, will try to do better next time.”

Hope you’ll join me for the next installment of Charles’ story.