By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

Today we return to the 1917 diary of Gertrude Codman Carter. You may read the previous entries here:

Introduction | January | February | March | April | May

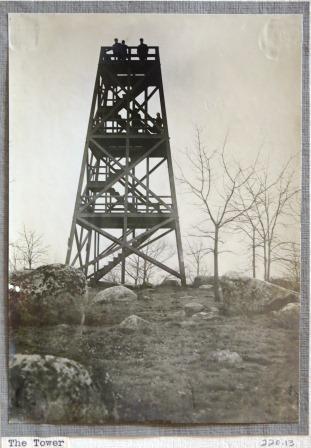

Unusual for this diary is a long unbroken series of entries from 1 June – 20 June without any missing pages (though we then skip to 26 July with a series of torn-out entries). The beginning of June documents a bustling social schedule punctuated by trips to Ilaro to view or supervise the ongoing construction. In the final June entry, for example, “sever rain” led to two separate trips to Ilaro in order to examine the damage done when gutters “behaved awfully.”

The distant war also enters back into the frame of English colonial life when Gertrude takes her son John to a church service held to send off the troops. “We both loved it!” she reports, with a rare exclamation point, describing the sermon as “splendid” and making note of two particular hymns that were played by the band.

We also see hints of relationship drama in the recurring figure of Harold Austin who is first mentioned on 9 June as the instigator of an outing in search of some wood flooring, presumably for Ilaro. He then turns the shopping excursion into a dinner party and, at some point during the evening “unburdens his soul” to Gertrude about “having a time of it with the fair Kitty.” He confided in her that “[he] has suddenly decided to go to England.” Four days later, Gertrude notes: “Harold Austin left suddenly today.” Whether to retreat from or in pursuit of the fair Kitty, we are left guessing.

Here is Gertrude’s June in her own words.

* * *

1 June.

Miss Barton to the house.

2 June.

Paid calls and to the Savannah.

3 June.

Ilaro with John. We have much fun in the [illegible] house planning & playing together. To the [illegible] & visited his coral caves.

4 June.

A luncheon party before the races. The Kings, the Clarence Haynes, Captain Hancock (Charlie Haynes could not come) who was so charming to me. I had a delightful afternoon. John and Mickey came too.

Gymkana at the Savannah.

5 June.

More home carving.

7.30 dined with Mrs. Carpenter.

6 June

Subcommittee on Savannah improvements

1. Improvement committee

Miss Burton at 4.30 carving.

7 June.

llaro.

Governor House at home.

8 June.

Another Savannah meeting.

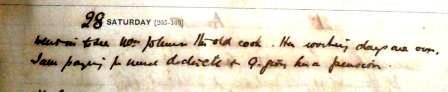

9 June. Saturday.

Harold Austin about some nice wood he has for a floor. Such an amusing afternoon. We drove out to Blackman Plantation to a stone and garden [illegible] there. G. promptly disappeared into the woods with Mrs. H. H. Sealy so tripped off with Harold myself, who had just joined us and was looking so nice in his new uniform. Then had my fortune told! Harold Austin gave a dinner party to whoever he could find — Mr. Fell & Mrs. Frank [illegible] was coralled first & then Mrs. Carpenter who had a [illegible] & was quite ready to [illegible] …so Frank Austin & Mr. Carpenter very serious were produced & then Harold Austin sank exhausted next to me & unburdened his soul. He is evidently having a time of it with the fair Kitty & has suddenly decided to go to England. After supper we had a go at the theater. Harold Whyte came too & it was all fine hours later.

10 June. Sunday.

Mrs. Austin had a picnic for the kids only we had it in the house because it rained.

11 June.

Ilaro.

A [illegible] party with Mrs. Sean Evelyn. Laddie. Mrs. DaCosta.

12 June.

Swim

Ilaro.

Called Carpenters & Evelyns.

Took Miss Mary & Mrs. Sealy to house.

13 June.

10. [illegible] meeting

1. Theatre Co. meeting

To C.P. Clarkes at home

Charlie Haynes afterward

Harold Austin left suddenly today

14 June.

Savannah dull.

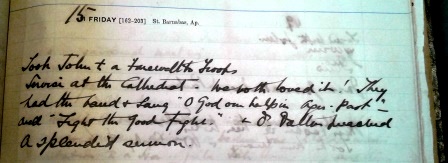

15 June.

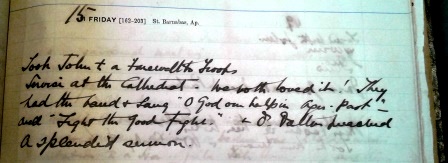

Took John to a farewell to troops.

Service at the Cathedral. We both loved it! They had the band & sang “O God Our Help in Ages Past” and “Fight the Good Fight.” & Fr. Dallin preached a splendid sermon.

16 June.

Ilaro.

Took John to Bazaar.

¼ h8. Dinner party at Mrs. Charlie Sealey’s. Great fun. Talked politics afterward.

18 June.

Mrs. Austin & kids & we took our [illegible] to Maxwells. Afterward [illegible]. Victrola Magic Lantern.

19 June.

Tour with John.

Ilaro.

[illegible] tour at [illegible] Parks.

Miss Packer re her [illegible].

C Hayden for sunset.

20 June.

Severe rain.

Ilaro. Gutters behaved awfully.

Ilaro again to see the damage.

* * *

As always, if you are interested in viewing the diary or letters yourself, in our library, or have other questions about the collection please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.