By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

Today we return to the 1917 diary of Gertrude Codman Carter. You may read the previous entries here:

Introduction | January | February | March | April | May

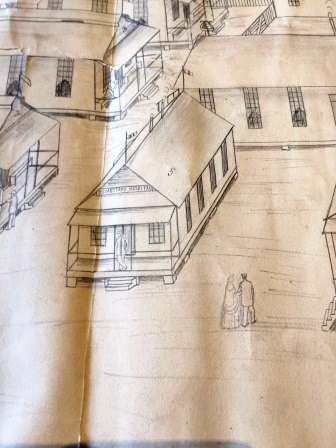

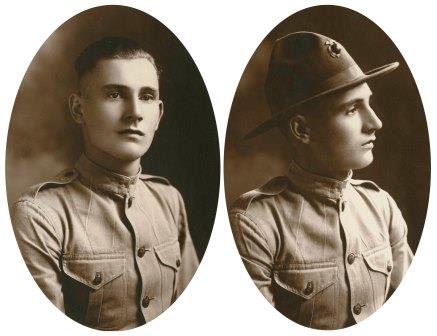

Gertrude spends the month of August preparing to move her family — son John, husband Gilbert (“G.” in the diary), and the family servants — to Ilaro Court, the mansion she designed and oversaw the construction of that today serves as the official residence of the Prime Minister of Barbados.

On August 8th Sir Gilbert departs Barbados for the neighboring island of Trinidad, taking with him one of the household servants, Wickham to serve as his valet and necessitating the temporary loan of a young man, Cyril Toppin, from the Law family residence to serve as under butler in Wickham’s absence. The sixty-nine year old Sir Gilbert was, it seems, more interested in being spared the fuss of moving than he was in assisting his younger wife (twenty-seven years his junior) with the logistics of household relocation.

Gertrude, who seems used to daily life on her own, carries on with her social life, her work, and her volunteer commitments even as she travels to Ilaro on a regular basis to unpack, supervise final construction — “So now the thing is to rush along & get the top story done — anyway the windows and side of it”! It is perhaps with pride and relief that she can sit down and report on the final day of August that “all our trunks went up to Ilaro today.” They would be able to begin the month of September in their new home.

* * *

Aug 1.

Ilaro, unpacking boxes.

1pm Improvement Society.

Ilaro again.

Aug 2.

Town.

Women’s Self Help.

Civic Circle here at [Charleston?]

G. paid calls.

Aug 3.

Theater meeting.

Took John [to] band at the rocks.

Aug 4.

[Illegible] in the garden. [Showering?].

Aug 5.

Hurricane Sunday. All to church.

Wet p.m.

Dined at B[illegible]. Majors [illegible]. Delightful evening with new victrola “Chant des Belges!”

Aug 6.

Mrs. Law sent a boy to me for an under butler — someone must act for Wickham. G. is going away while we move in & taking Wickham as valet. This seemed a very young little person but his mother is the Laws waitress & he is a boy scout. Name Cyril Toppin.

Mr. Eustace came to lunch & discussed theater.

Colm Davies came to tea & Mr. Fell.

Aug 7.

Plans finished — at least they should have been but I found I had more work on them than I expected.

I called at Government House. Out.

Sunset at “Chan Chan” ‘s as Baby Manning calls Charlie Sealys.

Aug 8.

G. left today with Wickham for Trinidad to stay with Sir Norman Lamont & then to go to Tobago with him. He said he did not intend to return until we were settled. So now the thing is to rush along & get the top story done — anyway the windows and side of it.

…who had for the first time in history conceived a dinner party for the Bishop of [Devonshire?] who proved to be a most interesting man. Mr. Fell & [illegible] were there and the chairs & glass were lovely & old & the [illegible] dinner very good. The Claret too was irreproachable. I went & returned with Mr. Fell in his [illegible].

Wednesday 22nd & Thursday 28th

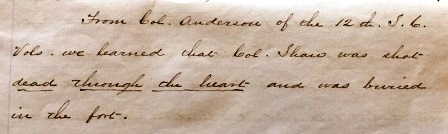

But today I spent at Ilaro & found its upper [illegible] rooms a solace & a place to think. I began to realize that not only was [illegible] gone but that in all probability I would never see Basil Blackwood again. I tried to imagine England & especially London without them & I felt I never wanted to see it again. How good they had both been to me & I must try to be thankful for the past.

Aug 24.

To [illegible] party at the Ashtons — only eight of us, very nice. Her baby is such a darling, so friendly. I walked there & back. Oh how hot it was!

Aug 25.

Car came back but not itself quite. To Ilaro in the morning.

Aug 26.

To Mrs. Manning’s.

Mr. Fell came in late.

Aug 27

Took Small up to Ilaro to rub horses. Clarissa & Sarah are serving there.

To Self Help with Mrs. Carlin; planning alternations.

Aug 28.

John to dentist.

Laddie drove me to Spikestown & back a [illegible] dreary time.

Aug 29.

Again to Spikestown to a [illegible] meeting with Mr. Leslie & Lady Probyn & Mrs. Luce. A shower arose & got up to put my parasol over Lady Probyn; when it exploded & left only ribs we got quite merry over it. Also over Mr [illegible] who proposed “a [illegible] heart of thanks to H. E. the Governor.”

Aug 30.

[Torn paper] party at the Cove. L. drove me out. The Charlie Sealys & Clarence Hayes, Mr. & Mrs. Carpenter, Frank Austin & a nephew. We had tea at the Clarence Hayes’ first & quite fun. Clarence Hayes & I sat on the Cove beach & pretended to have a desperate flirtation to the [illegible] of Mrs. Carpenter above.

Aug 31.

To Charlie Sealys for [illegible].

All our trunks went up to Ilaro today.

* * *

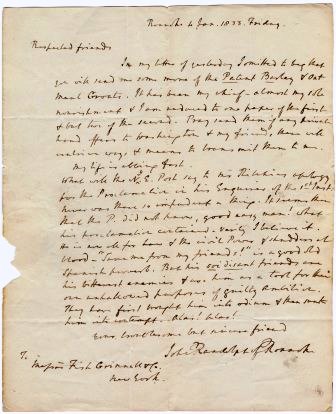

As always, if you are interested in viewing the diary or letters yourself, in our library, or have other questions about the collection please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.