By Brendan Kieran, Reader Services

In Boston’s South End: The Clash of Ideas in a Historic Neighborhood Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2015), Russ Lopez constructs an engaging historical account of the South End from before the start of its development as a neighborhood in the 1850s through the time of his writing (22). Lopez, who lives in the South End, teaches in the School of Public Health at Boston University and has written books and articles on topics relating to urban environments (285). This background is on display in his writing as he integrates a variety of social developments and changes in the neighborhood over time into a coherent, highly-readable work.

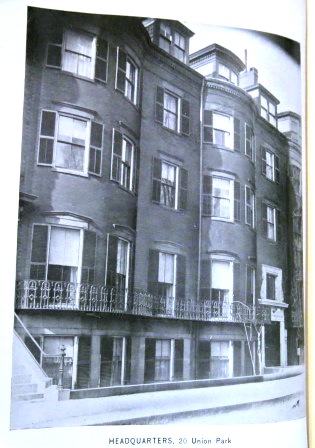

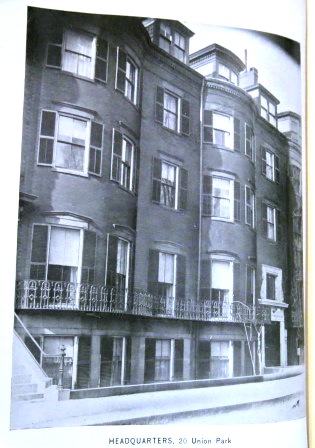

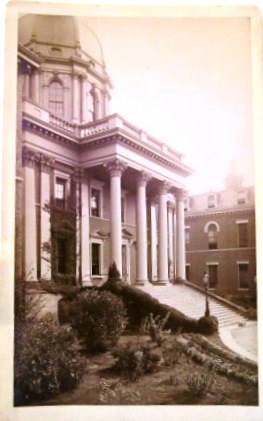

“HEADQUARTERS, 20 Union Park,” from South End House: Longer and Shorter Retrospects 1891-1911 by the South End House ([Boston, 1912]).

Lopez challenges a widely-held narrative of glorious early years, decades of decline and squalor, and later resurgence in the South End, and sheds light on “a much more nuanced history” (xi). He does so utilizing “public records, newspaper articles, older books, published reports, and the personal papers of past and current residents” (ix). Beginning in the Ice Age, Lopez discusses the Indigenous populations of the area, the early settlement of Boston by Europeans, and the development of the neighborhood in the 19th century. He then looks at the various populations that have inhabited and worked in the South End over the years, including Irish and Jewish immigrants; Black, Latino, and gay and lesbian communities; and, more recently, the wealthy white people who have come to dominate the neighborhood.* He also documents the churches, housing, social and cultural organizations, forms of work, customs, and other aspects of life that these residents have created, participated in, and used to shape the neighborhood.

The second half of Lopez’s book largely covers the urban renewal period of the 1950s to 1970s and the developments in the decades that have followed. He explores the actions of city agencies and officials, as well as the drastic displacement and demographic changes that occurred beginning in the mid-20th century. The urban renewal period was very a challenging one in the South End, marked by tensions between the city and residents as well as turmoil along racial lines among residents. Lopez frames the second half of the 20th century to the present as a time of social and economic pressure for low-income people in the neighborhood, with gentrification and rising prices being a near-constant feature of South End life. However, he chronicles the community resistance of these decades, including various organizations that pushed back against economic violence and pursued their own plans, earning some successes such as the creation of the Villa Victoria housing development (168-170).

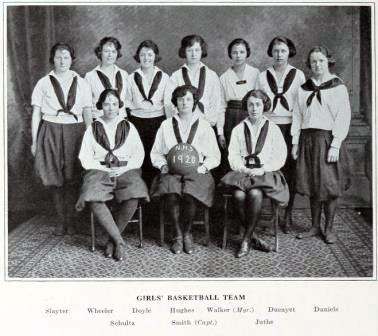

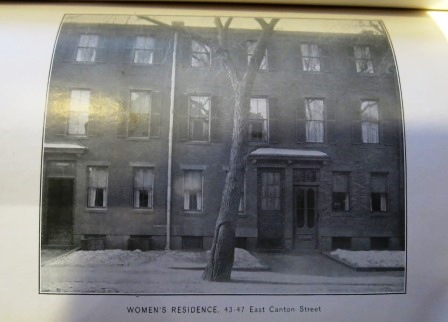

“WOMEN’S RESIDENCE, 43-47 East Canton Street,” South End House, from South End House: Longer and Shorter Retrospects 1891-1911 by the South End House ([Boston, 1912]).

Lopez in many ways provides an engaging social history of the neighborhood and its connections to the city of Boston as a whole. He successfully charts the developments and changes within the South End’s religious communities, documents the importance of the South End for decades as a center of Boston’s Black community (91-92), and chronicles the many implications of urban renewal on the neighborhood. Lopez not only challenges the established narrative, he redefines it. His emphasis on forms of housing, employment, recreation, and other aspects of life allows him to really explore the social and cultural fabric of the neighborhood over time. Furthermore, by noting the differences in housing types, income levels, and other demographic differences within various sections of the neighborhood, he is able to create an intricate view of the South End over time. His prose is complemented by a variety of photographs throughout the book.

While the depth of Lopez’s research and his emphasis on the geography of the neighborhood are impressive, he occasionally leaves a desire for a closer look at certain social and cultural developments and groups in the city, such as the briefly-mentioned Syrian population in the mid-20th century (69, 144). Additionally, some editorial decisions leave room for potential challenges. For example, while the book includes some maps, more of them could have been helpful for making sense of the close, detailed descriptions of the neighborhood offered by Lopez. In addition, Lopez cites some letters without providing collection or publication information, which could present difficulties for researchers who would like to track down those sources (40-41). Ultimately, these issues do not prevent Lopez from accomplishing his goal of writing a complex and illuminating story of the South End’s existence over time.

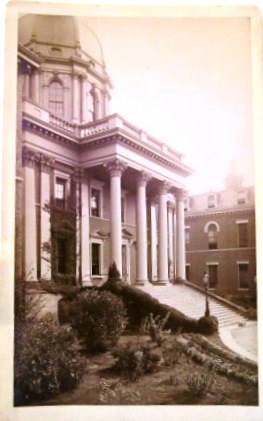

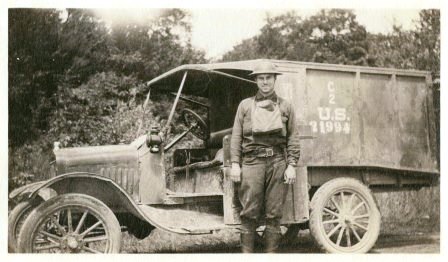

Boston City Hospital, 1880s. Taken by Allen & Rowell. In Photographic Views of Boston, Mass., Box 3, #12.175.

This book may be of interest to historians of Boston’s neighborhoods; urban historians in general; historians of urban geography and the built environment; scholars of urban renewal; historians of race in Boston; and historians of Boston’s Black, Latinx, and LGBTQ communities. There is much in this book for academic researchers and community historians alike; it is also a worthwhile and accessible text for a casual reader who is interested in learning a bit more about Boston’s history.

*In recent years, “Latinx” has gained popularity as a gender-neutral term. I use “Latino” in this paragraph to reflect the language used by the author in the book.

Related Materials

Manuscript Collections

Sarah Pananty Writings and Bibliographies, [193-]-1940.

South Congregational Church Records, 1828-1929.

Robert Treat Paine Papers II, 1733-1965; bulk: 1880-1949.

Henry Lee Shattuck Papers, 1870-1971.

Walter Muir Whitehill Papers, ca. 1941-1978.

Print Materials

Neighbors All: A Settlement Notebook by Esther G. Barrows (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1929).

Chain of Change: Struggles for Black Community Development by Mel King (Boston: South End Press, 1981).

“Report to the Massachusetts Legislature, by the Committee on Education : in favor of an appropriation of $5,000, to the Female Medical Education Society, together with the constitution, names of officers and members, and other information respecting the Society, and the Boston Female Medical School” by the Massachusetts General Court Joint Committee on Education (Boston: Female Medical Education Society, 1851).