By Susan Martin, Collections Services

This is the fifth post in a series about the wartime experience of Charles Cornish Pearson. Go back and read Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV for the full story.

Today we return to the letters of Sgt. Charles Cornish Pearson of the 101st Machine Gun Battalion, serving in France during World War I. By the early summer of 1918, Charles had been serving for a year, and he wrote more often about specific things at home that he missed. His letters are peppered with wistful reminiscences of family vacations and home-cooked food. He longed to spend an evening just listening to records or taking in a movie (though war movies had lost their appeal, he said). He also missed his young nieces and nephews. In early June, he wrote to his sister-in-law:

Glad to hear the “kiddies” are well. My how I would like to see them. Believe me I think of them often, especially when I run across French youngsters. It is quite a common occurence when in a town for a couple of the youngsters to run up to you, & grab hold of your hand & walk along with you, & you know that cann’t help but make you think of the little ones at home & wonder how they are.

The month of June was fortunately short on “hair raising experiences.” As always, Charles reassured his family that he felt well and optimistic about his chances of survival. He lovingly scolded his mother for worrying, telling her, “They haven’t got me yet.” To his brother Bill he wrote, “I am a great little shell dodger […] but when they come down OH MY, what a sensation, makes you long for home & a little peaceful scenery.” However, while no fan of the military life, he wondered if he’d be able to adjust after the war.

Haven’t sat down to a table to a meal for so long that I am afraid I wouldn’t know how to act. […] Fear greatly that I will get so accustomed to this life that when I get back in the states, I will have to build me a dugout in the backyard to live in, won’t be able to live in a steam heated apartment. Will be kind of tough on my wife.

At the end of the month, the 101st Machine Gun Battalion was on the move again. Of course, Charles was circumspect about his location, so I consulted Philip S. Wainwright’s History of the 101st to fill in the details. Wainwright describes several stops on the way to the battalion’s final destination in the woods near Montreuil-aux-Lions. This was an active sector.

Charles wrote to his parents from this position on 15 July 1918. It would be almost two weeks before he wrote another letter to anyone—an unusually long gap in his correspondence. What happened during that gap? The Battle of Château-Thierry.

Wainwright’s history contains a detailed description of the fighting at Château-Thierry, including troop movements, strategy, etc., as well as the battalion’s pursuit of the retreating German army to Trugny. But Charles was taciturn. In a brief and apologetic letter dated 28 July, his first after the battle, he explained to his parents that he didn’t “feel much in the mood for going into details […] One sure does lead a pace when things are breaking the way they have and you often wonder how you keep going.” He was clearly shaken.

Charles opened up about the battle a few days later, in a series of longer letters to his family. His account is harrowing. There were no trenches, dugouts, or sheltered emplacements in this sector, so the troops’ position was unprotected except for a few sparse patches of woods and hastily dug holes. The men of the 101st were forced to haul their heavy machine guns, sometimes by hand, back and forth over many kilometers of damaged roads. Rations were small to nonexistent. To top it all off, the fighting took place during a heavy thunderstorm. As Charles wrote to his brother Bill on 4 August:

Would like to relate to you all my experiences of the past month but […] certain of them are not pleasant ones and the less said about them the better.

Sure have had my belly full of war the past month & suppose have come as near to being killed as I ever will be until my time comes. One gets to be a fatalist over here (except when one is dodging shells) as often times one gets the hardest knock when things are seemingly most peaceful.

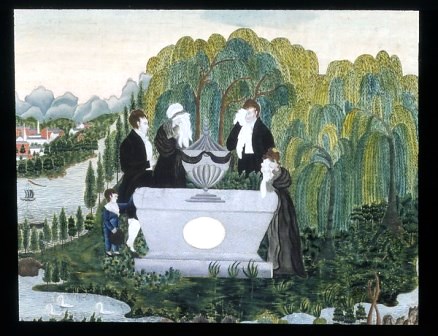

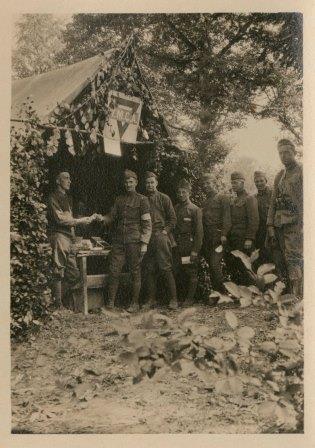

The details of Charles’ account are confirmed by Wainwright, who states that “more was learned in the short time between the 18th and 26th than could possibly have been taught by years of maneuvers” (p. 43). Wainwright’s book also helped me to identify one of the photographs that came to the MHS with Charles’ papers. Below is an image of the graves of William Alfred Bruton, Paul Watson Butler, and Andrew Smith (a.k.a. “Duke”) Wellington. The three men were killed by shell fire on 25 July 1918 and buried in La Fère Woods. All were members of Charles’ company.

Beginning on 2 August, the men of the 101st were billeted in the peaceful town of Courteron and enjoyed ten well-deserved days of rest. They swam in the Marne River and caught up on their letters home. Officers and non-commissioned officers, including Charles, were granted a 48-hour leave to see the sights in Paris.

Join me in a few weeks for Part VI!