By Alex Kouroriez, Intern

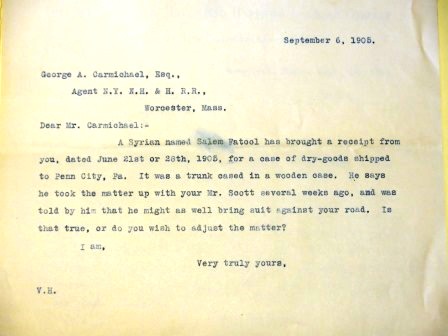

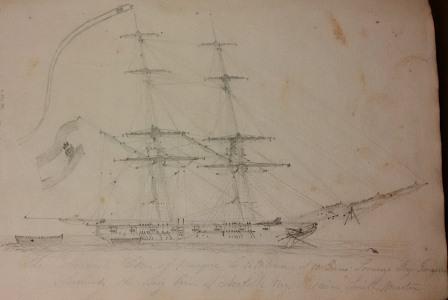

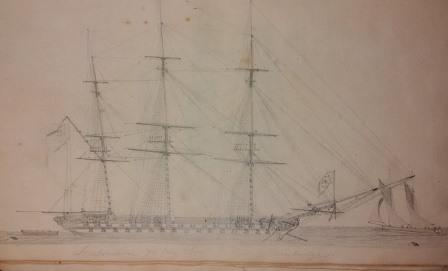

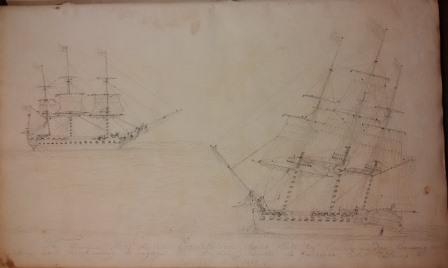

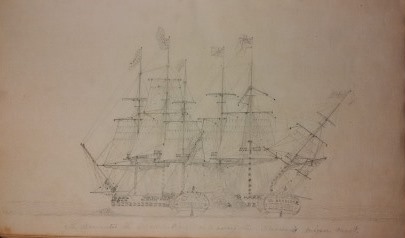

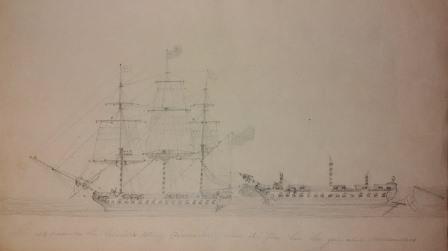

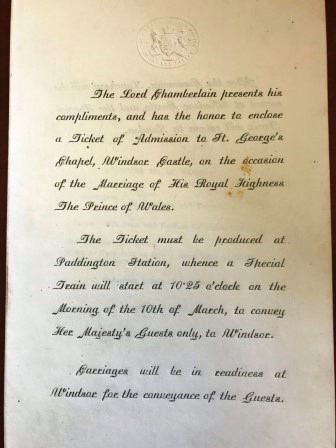

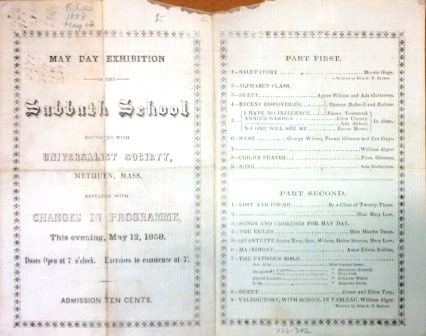

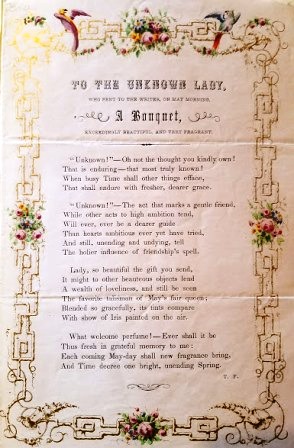

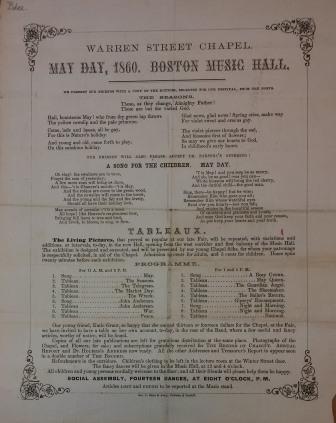

Anna Peabody Bellow’s 1864 travel diary documents her voyage to England and France as a young and wealthy New England young woman during the Civil War. Included among her paragraph-a-day entries are watercolor and pencil sketches, perspective as a tourist in Europe, and a reminder that some things never change.

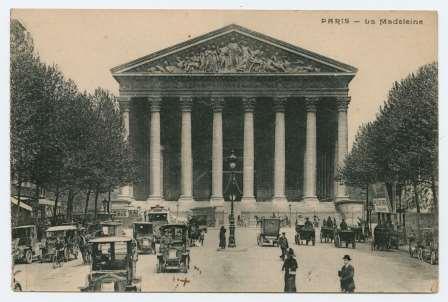

The Paris Bellows describes is under the Haussmann renovation and many famous landmarks make cameos in her diary. She records sights such as the Champs Elysees, the Madeline, Notre Dame, and the Pantheon, which she described her visit as “a little uncomfortable visiting the tombs underneath.” I had a similar experience visiting the Pantheon crypt a few years ago, but seeing the resting place of legendary French writers was worth the chill.

Though a tourist in the 1800s, Bellows’ account of Parisian museum going could be a post on TripAdvisor. In an entry, Anna Peabody Bellows and her brother-in-law Charles are turned away from a museum without a ticket, “However by some hocus pocus Charles soon got in of course.” I’m amused that charming one’s way into museums is not recent practice, and Bellow’s dry humor regarding museums does not stop there. At the Louvre’s sculpture gallery her blasé tone is incredible: “These much disappointed. Venus of Milo really the only thing we appreciate.”

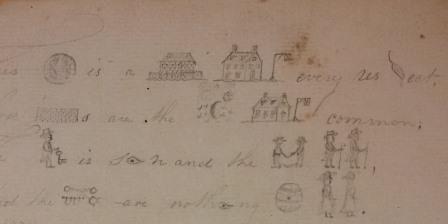

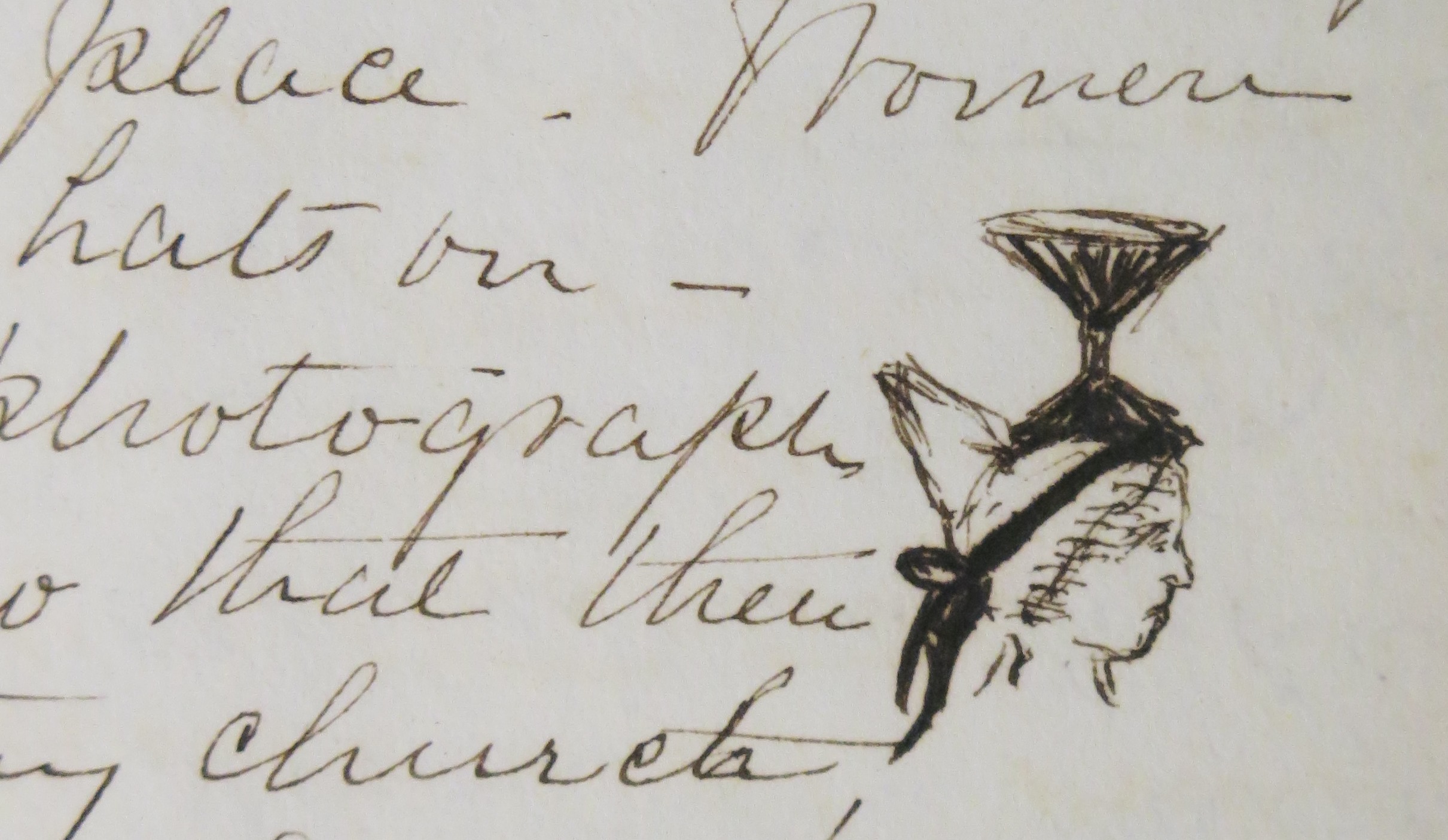

Bellows and her entourage vacationed in Europe during the Civil War with little reference to current events in her diary full of social calls, travel itineraries, and statements of health. I wonder her reason for traveling to Europe in the midst of a war and if she felt more anxiety for her country beyond the page. While the daily entries are short, they capture the essence of the day in the lists of monuments visited and names of the people with whom she dined. In the lists of sight-seeing, she includes sketches to prompt her memory.

For example, she meets “women with very funny hats on” as they wear traditional Lyonnais dress for a summer festival.

As a high school student preparing to take a gap year to study in Tours, France, I feel encouraged to keep my own travel journal for the sake of being fashionable in the 1860s. Inspired by Bellows’ diaries, I would like to capture my surroundings not only through words but also in my amateur watercolor illustrations. I would like to research into the reason for the Bellow’s family trip during the Civil War, but in the meantime, I make the connection: Bellows left the Boston she knew well to see France, as I will this fall. While I’m not leaving the country during a war, Bellows and I have looked to Europe for a brief escape, in my case, one year of studying language for pleasure before jumping into four years of academics.

All in all, this journal is a delight for its pointed observations, illustrations, and addition to the account of Americans in Paris. If you are traveling this summer visit the library to check out this diary or other travel dairies at the MHS for inspiration on journal keeping.