By Susan Martin, Collections Services

I’d like to take this opportunity to tell you about two terrific collections available for research at the MHS, the papers and photographs of Nathaniel T. Allen of West Newton, Mass. The Allens were a truly remarkable family. Nathaniel, his wife Carrie, and their three daughters (as well as many other relatives) were educators and reformers of the 19th and 20th century, and these fascinating collections are a very welcome addition to our library. I processed the photographs, and my colleague Laura Lowell processed the papers.

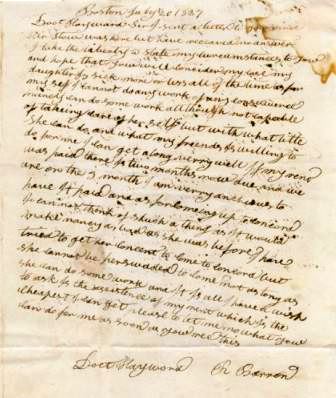

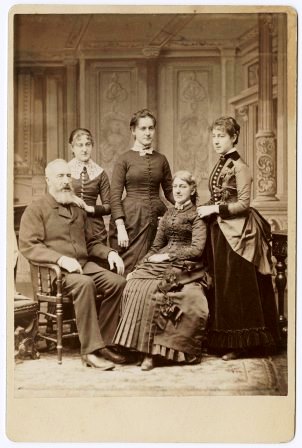

This cabinet card photograph (Photo. #247.311), taken in 1882, is my favorite of the Allen family. Seated are Nathaniel Topliff Allen (1823-1903) and his wife Caroline Swift (Bassett) Allen (1830-1915). Standing behind them, from left to right in reverse age order, are their three children: Lucy Ellis Allen (1867-1943), Sarah Caroline Allen (1861-1897), and Fanny Bassett Allen (1857-1913). A son, Nathaniel, Jr., had died as a child.

Nathaniel Allen was the founder and principal of the West Newton English and Classical School (familiarly known as “the Allen School”) from 1854 to 1900. The school was progressive, co-educational, and integrated, and its student body included African American, Latino/a, and Asian boys and girls, as well as international students. It was also one of the first schools to incorporate physical education into the curriculum. Nathaniel’s wife Carrie worked with him to run the school and look after the students, many of whom boarded in various Allen family homes. Several aunts, uncles, and cousins also served as teachers and administrators.

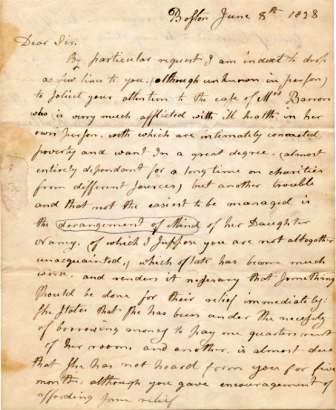

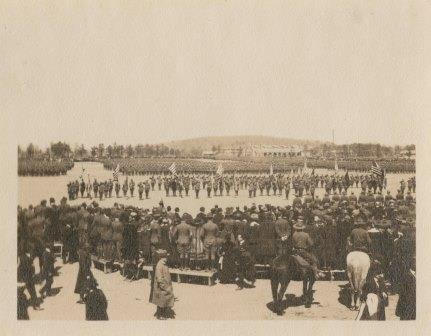

This photograph (Photo. #247.874) of the Allen School at 35 Webster Street, West Newton, dates from 1886. Carrie is seated in the middle wearing a light-colored shawl, with Nathaniel immediately to her right. You can also see some exercise equipment in the yard.

After Nathaniel died in 1903, his oldest and youngest daughters, Fanny and Lucy, opened the Misses Allen School for Girls at the same location. Their middle sister Sarah, unfortunately, had died in childbirth in 1897 at the age of 36.

Laura and I processed the papers and photographs concurrently, and I think our work really benefited from the collaboration. We arranged the collections to mirror each other, for the most part, with separate series of family and school material. This division was trickier than it sounds, because many family members were also teachers and students. I frequently had to move photographs from one section to the other as I figured out who everyone was. (For more information about how we process photographs at the MHS, see my earlier Beehive post.)

The photograph collection contains 1,030 photographs, primarily individual and group portraits of Allen family members and students spanning almost 100 years. While Laura got to know the Allens from their letters, diaries, and other writings, I got to know them from their faces. The collection was completely disorganized when it came to us, but by the end I’d gotten pretty good at identifying people and could even distinguish baby pictures of the three sisters!

It was a lot of fun to share information and compare impressions with Laura as we worked. When she came across a particularly interesting person, she was curious to see what he or she looked like. I also went to her to learn more about the people who intrigued me. For example, I loved the way Lucy, the youngest Allen, usually smiled directly into the camera while other subjects looked stiff or coy with a slightly averted gaze.

The story of the Allens has so many fascinating threads to follow that we hope these collections will be of interest to a wide variety of researchers. For example, Edwin and Gustaf Nielsen were two brothers who, through the intervention of the poet Celia Thaxter, were taken as wards into the Allen home and became de facto members of the family. There’s also Fanny Allen’s decades-long friendship with Pauline Odescalchi, Princess of Hungary. Not to mention the fact that the Allens played an active part in the anti-slavery, suffrage, temperance, peace, and educational reform movements, rubbing elbows with the likes of William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, Horace Mann, and Lucy Stone.

Nathaniel and Carrie Allen had no surviving grandchildren. Fanny and Lucy never married, and Sarah’s only daughter died two days after she did in 1897. But this family of teachers clearly had a profound and far-reaching influence on the thousands of boys and girls who attended the Allen School and Misses Allen School. Among them were future writers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, activists, soldiers, at least one actor, and a Supreme Court justice. In my next post, I’ll tell you more about them.