The Elm Hill Private School and Home in Barre, Mass.

By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

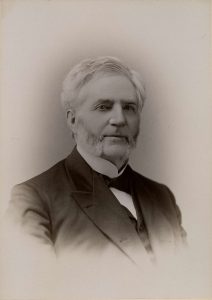

The Elm Hill Private School and Home for the Education of Feeble-Minded Youth in Barre, Mass. was the first school of its kind in the United States. It was founded in 1848 by Dr. Hervey B. Wilbur, and Dr. George Brown took over as superintendent three years later. The MHS holds a small collection of George Brown papers, including correspondence, financial documents, and printed items related to this ground-breaking school. Here’s a picture of Dr. Brown from the George Brown family photographs.

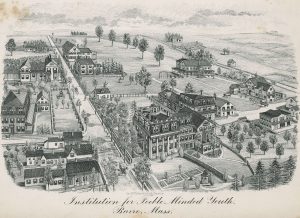

A promotional broadside from 1864 declared that the Elm Hill School “offers the best educational advantages for children and youth, whose different phases of mental infirmity unfit them for receiving instruction by the ordinary methods, and at the same time provides a permanent home for those who desire it, where every comfort which wealth can procure is furnished.” Of course, only families with means could afford to send their children to this exclusive and remote private institution, and some students came a long way to attend.

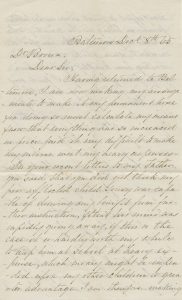

The collection includes a few folders of letters from students’ family members, and these can be mined for some tantalizing details. For example, one 1865 letter relates to Elm Hill student Gouverneur Heiskell. Gouvy, as his family called him, was born in 1847 or 1848, and his great-grandfather was none other than President James Monroe. After the Civil War, Gouvy’s family found itself in tough financial circumstances, so his mother wrote to Dr. Brown.

In your recent letters to my Father you said that you did not think my poor afflicted child Gouvy was capable of deriving any benefit from further instruction, & that his mind was rapidly giving away, if this is the case it is hardly worth my while to keep him at school at heavy expense, which money might be expended upon my other children to greater advantage. I am therefore making every effort to find some respectable family living in the country who would be glad to take him for a moderate sum, & take care of him treating him kindly & giving him good food & lodging. I find myself in a fair way of doing this in some German families, but before they make any arrangements they require a statement of his case, that is if he is harmless easily managed &c &c […] I never shall forget yours & Mrs Browns kindness & shall always number you among my friends […] I should like very much to have a Photograph of Gouvy.

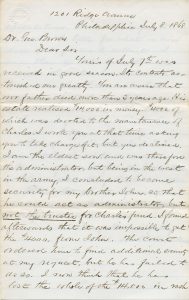

One particularly interesting story is that of the Kollock family. Charles Kollock was an Elm Hill student from a large Philadelphia family. His father, Rev. Shepard Kosciusko Kollock, died in 1865, leaving his children $14,000 in ready money. At that time, the reverend’s oldest son Matthew was serving with the army in California, so brother John agreed to act as estate administrator. However, by late 1867, the family’s account with Elm Hill was in serious arrears, and John wrote anxiously to Dr. Brown that he was having trouble coming up with the money.

I am aware, that your patience with me, is well nigh exhausted, and that you feel that you cannot keep my brother any longer unless your bills are paid. I have been trying very hard to get Charles’ money in such a shape, that there will be no further difficulty […] It is the desire of all my family, as well as myself, that Charles should remain with you, if you will keep him.

Eventually oldest brother Matthew, somewhat confused, contacted Dr. Brown directly.

I have heard nothing from my brother Charles for more than two years, and feel anxious to hear from you direct, how he is, and also whether his board and tuition is paid promptly, when it is due by my brother John. I do not like to ask him questions about it as he seems to dislike to answer them.

Dr. Brown replied immediately, and just five days later Matthew wrote again, “astonished” to hear about the unpaid debt amounting to hundreds of dollars. He explained that fully $4,000 of their father’s $14,000 had been designated for Charles’ support, and he suspected that John had lost the entire sum in “rash speculations.”

Matthew asked Dr. Brown to send him the outstanding bills and resolved to bring a case against his brother for “breach of trust.” He also called John out for lying about an army appointment. Eventually sister Mary reached out to other relatives, who helped with Charles’ expenses.

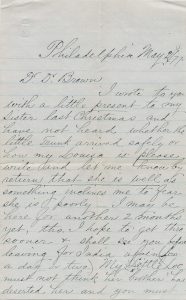

James Reynell, an India merchant, also lived in Philadelphia, and his sister attended the Elm Hill School. Here’s an excerpt of an 1877 letter to Dr. Brown.

I wrote to you with a little present to my Sister last Christmas and have not heard whether the little Trunk arrived safely or how my Louisa is. Please write and let me know by return that she is well as something inclines me to fear she is poorly. […] My Little Loo must not think her brother has deserted her and you must kindly keep me in her memory even if I do not write so often as I ought. Please tell her I send kisses & love […]

The Elm Hill School was known by many names over time, reflecting the evolution of its mission and probably changing sensibilities. Some of Elm Hill’s previous (and very unfortunate) names included the Institution for the Education of Idiots, Imbeciles, and Children of Retarded Development of Mind (ca. 1851) and the Private Institution for the Education of Idiots, Imbeciles, and Backward and Eccentric Children (ca. 1853-1855). “Imbecile” was dropped sometime after 1858, and “Children” became “Youth” before 1870.

George Brown superintended the school for 40 years, until his death in 1892. At that time, though other schools for the “feeble-minded” had since been established, Elm Hill was the largest private institution of its kind in the country. Dr. Brown’s son George Artemas Brown succeeded him as superintendent, followed by his son George Percy Brown. The institution closed in 1946, 98 years after its founding.

The George Brown papers fill only one document box, and these letters represent just a fraction of Dr. Brown’s overall correspondence. They give us a fascinating glimpse into his work in Barre, but tell us very little about the students themselves or their education. Interested researchers will find additional material in a collection of Elm Hill School records at the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. That library also holds some Brown family papers, primarily those of later generations.

Founder to Founder

By Sara Georgini, The Adams Papers

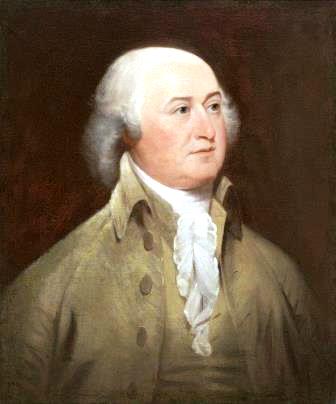

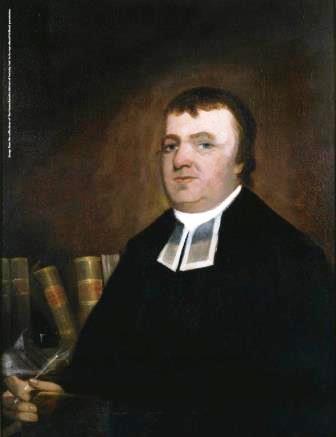

Like so many good stories here at the Historical Society, it began with a reference question. Jeremy Belknap, hunting through his sources, asked Vice President John Adams for some help. Belknap, the Congregationalist pastor of Boston’s Federal Street Church, had spent the past few years amassing manuscripts for several major research projects. By the summer of 1789, he was deep into writing the second volume of his History of New Hampshire, a sprawling trilogy that he built, slowly, with meticulous footnotes. The clergyman, who honed his narrative skill as a Revolutionary War chaplain and biographer, felt thwarted by a lack of access to key documents.

John Adams, 1735-1826.

Jeremy Belknap, 1744-1798.

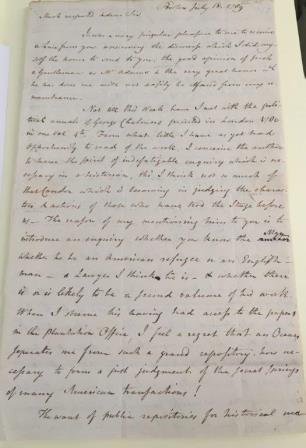

After poring over George Chalmers’ Political Annals of the Present United Colonies from their Settlement to the Peace in 1763 (London, 1763), Belknap wrote to Vice President John Adams to see if he knew more about the Scottish antiquarian’s research methods. Mainly, Belknap wanted to see how Chalmers pieced together his saga of America as a “desert planted by English subjects” and made fruitful by the flourishing of English liberties. On 18 July, Belknap wrote: “When I observe his having had access to the papers in the plantation Office, I feel a regret that an Ocean seperates me from such a grand repository. how necessary to form a just judgment of the secret springs of many American transactions!” Jeremy Belknap’s query – and Adams’ detailed reply – form one of the most significant exchanges that we will feature in Volume 20 of The Adams Papers’s The Papers of John Adams (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020).

Though the nation was new, Americans like Belknap hungered to capture their history in print. While British scholars flocked to the Society of Antiquaries of London and dug through government office records, early American scholars lacked similar institutions and resources to conduct historical research. Across Massachusetts, precious family manuscripts and rare artifacts piled up in private homes and flammable steeples. When Belknap looked around Boston in 1789, he lamented how fire and plunder had ravaged materials held in the city’s courthouse (1747), the Harvard College Library (1764), Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson’s home (1765), the Court of Common Pleas (1776), and Thomas Prince’s cache at the Old South Church (1776). Belknap began sketching out what became the Massachusetts Historical Society: a scholarly membership organization (of no more than seven!) that collected materials and published research. He found a fellow visionary in John Pintard, who led efforts to found the New-York Historical Society.

Jeremy Belknap to John Adams, 18 July 1789, Adams Family Papers.

Adams and Belknap had traded letters before, and they would continue to do so until the pastor’s death in 1798. This one touches directly on his plans to create the Society. Founder to founder, Belknap put the problem plainly:

The want of public repositories for historical materials as well as the destruction of many valuable ones by fires, by war & by the lapse of time has long been a subject of regret in my mind. Many papers which are daily thrown away may in future be much wanted, but except here & there a person who has a curiosity of his own to gratify no one cares to undertake the Collection & of this class of Collectors there are scarcely any who take Care for securing what they have got together after they have quitted the Stage. The only sure way of preserving such things is by printing them in some voluminous work as the Remembrancer—but the attempt to carry on such a work would probably not meet with encouragement—

John Adams to Jeremy Belknap, 24 July 1789, Belknap Papers.

In Adams, Belknap found a high-profile ally. A longtime supporter of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the statesman had championed the new nation’s intellectuals abroad. He approved wholly of Belknap’s instinct. Despite his duties presiding over the Senate in the first session of the federal Congress, John Adams prioritized Belknap’s query, firing off a reply on 24 July. He shared a few thoughts on Chalmers’ work and filled in details of Revolutionary War history. Then John Adams lingered happily on Belknap’s dream of a historical society. He had a very personal stake in how the national story was told, after all, and he was eager to impart advice. Adams wrote:

Private Letters however, are often wanted as Commentaries on publick ones.— and many I fear will be lost, which would be necessary to shew the Secret Springs… some of these ought not to be public, but they ought not to be lost.— My Experience, has very much diminished my Faith in the Veracity of History.— it has convinced me, that many of the most important facts are concealed.— some of the most important Characters, but imperfectly known—many false facts imposed on Historians and the World—and many empty Characters displayed in great Pomp.— All this I am Sure will happen in our American History.

Encouragement from John Adams and others led Belknap to dedicate the following months to drafting a concrete plan for the organization’s future. On 24 January 1791, Belknap invited nine colleagues to join him in creating the Massachusetts Historical Society, following up with a detailed circular letter ten months later. John Adams and his family, all ardent advocates of Belknap’s mission to preserve history, have supported the Society ever since, in word and deed.

“Great sights upon the water…”: unexplained phenomena in early Boston

By Daniel Tobias Hinchen, Reader Services

I hear you haue great sights upon the water seene betweene the Castle and the Towne: men walking on the water in the night euer since the shippe was blowen vp or fire in the shape of men. There are verie few do beleeue it yet here is a greate report of it, brought from thence the last day of the weeke.*

The above excerpt is from the letter shown, dated 29 January 1643/4, written from John Endecott in Salem to Governor John Winthrop in Boston. In the weeks preceding this letter, a series of strange occurrences took place in Boston, and Winthrop recorded the events in his journal. It seems that the entries were written after the fact since Winthrop relates a couple of happenings in the same entry. The first event, though, was said to have taken place on January 18th of that year.

About midnight, three men, coming in a boat to Boston, saw two lights arise out of the water near the north point of the town cove, in form like a man, and went at a small distance to the town, and so to the south point, and there vanished away. They saw them about a quarter of an hour, being between the town and governour’s garden. The like was seen by many, a week after, arising about Castle Island and in one fifth of an hour came to John Gallop’s point.

Winthrop continues his entry recording matters pertaining to maintenance of Castle Island and defense of the town of Boston. But after just a paragraph, he returns to the topic of strange sights in the sky.

The 18th of this month two lights were seen near Boston, (as is before mentioned,) and a week after the like was seen again. A light like the moon arose about the N.E. point in Boston, and met the former at Nottles Island, and there they closed in one, and the parted, and closed and parted divers times, and so went over the hill in the island and vanished. Sometimes they shot out flames and sometimes sparkles. This was about eight of the clock in the evening, and was seen by many. About the same time a voice was heard upon the water between Boston and Dorchester, calling out in a most dreadful manner, boy, boy, come away, come away: and it suddenly shifted from one place to another a great distance, about twenty times. It was heard by divers godly persons. About 14 days after, the same voice in the same dreadful manner was heard by others on the other side of the town towards Nottles Island.

Writing after the facts, Winthrop made very little attempt at providing explanations for these occurrences. In the immediate journal entries there was only one bit that gave anything in the way of reasoning for what people saw:

These prodigies having some reference to the place where Captain Chaddock’s pinnace was blown up a little before, gave occasion of speech of that man who was the cause of it, who professed himself to have skill in necromancy, and to hav done some strange things in his way from Virginia hither, and was suspected to have murdered his master there; but the magistrates here had no notice of him till after he was blown up. This is to be observed that his fellows were all found, and others who were blown up in the former ship were also found, and others also who have miscarried by drowning, etc., have usually been found, but this man was never found.

Interested in finding out more? Consider visiting the MHS Library to work with the sources cited, or see the suggestions below for further reading.

*The transcriptions of the documents in this post appear as they do in the published volumes cited below, typically with original spelling and punctuation intact.

Sources

Endicott family papers, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Winthrop, John, The journal of John Winthrop, 1630-1649, Cambridge, Mass.: the Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996.

Winthrop papers, vol. IV, Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1944.

Further Reading

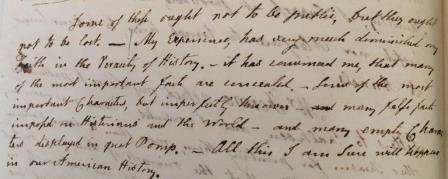

Images of the 1925 bombing of Damascus

By Adam Mestyan, Duke University and 2018-2019 MHS Andrew W. Mellon Fellow

These images are part of a series of 24 photographs of the October 1925 bombing of Damascus found at the MHS in the papers of Sheldon Leavitt Crosby,* a professional American diplomat in the interwar period. He was chargé d’affaires at the U.S. embassy in Istanbul from 1924-1930 and Acting American High Commissioner in Turkey in 1925. It is very possible that he acquired this series of astonishing photos from Damascus while acting in this capacity.

Damaged building in Damascus

Photograph by Luigi Stironi, circa 1925

Smoke rises over Damascus

Photograph by Luigi Stironi, circa 1925

Historians have recently begun to discuss the “greater war,” positing that the period of the First World War extended beyond 1914-1918. Indeed, after the Ottoman armistice, conflict and occupation continued in the Ottoman provinces well into the 1920s. In Damascus, the famous Emir Faisal (in fact, a general military governor appointed by the British) could not stop local notables and his own soldiers from proclaiming an independent kingdom with Faisal as king in March 1920. This desperate move was a pre-emptive strike against the implementation of the League of Nations mandates handed down at the San Remo conference in April of 1920, which gave France the mandate over Syria. It also came just a few weeks after the still-existing Ottoman assembly proclaimed their National Pact in Istanbul. Despite negotiations, the French government decided to put an end to the Syrian kingdom, and French soldiers occupied Damascus and other inland cities in July of 1920. Faisal was expelled from Syria and departed for the United Kingdom. But the Syrians stayed. From 1920 on, small groups engaged in guerilla actions and rebellions throughout the region.

In the summer of 1925, the series of events known as “The Great Revolt” in English scholarship and “The Great Syrian Revolution” in Arabic took place. In July, the mountain Druze population revolted against the French troops. Next, Damascus and Hama rose up against the French. There was also internal pillage and cross-ethnic-religious violence. On 18 October, the French army deployed tanks and airplanes around Damascus in retaliation. From six in the evening until noon the next day the French intermittently shelled the city. They did not warn the civilian population. The exact number of casualties is still debated but several hundreds died, including women and children. Although resistance continued in Ghouta (interestingly, also the last rebel-held location around Damascus in 2018) and the north, the massacre caused the recall of the French general in charge and a new Civil High Commissioner arrived to finally create a civil government.

Street scene in Damascus

Street scene in Damascus

Photograph by Luigi Stironi, circa 1925

Rubble in Damascus street

Photograph by Luigi Stironi, circa 1925

The photographs collected by Sheldon Crosby depict the destruction and casualties in Damascus and were taken by Luigi Stironi, an Italian in residence in Damascus active between 1921 and 1933. Some of these photos are clearly intended to evoke horror in the viewer and many were published in European newspapers and distributed as private propaganda. The American businessman Charles Richard Crane describes in his diary how a friend showed him very similar (if not the very same) images in Jerusalem in 1926. According to Daniel Neep’s Occupying Syria under the French Mandate, Stironi claimed in 1926 that his images were bought by an American diplomat. Although many of these photographs are well-known, it is rare to find such a comprehensive set among private papers. Is it possible that Crosby was the American diplomat to whom Stironi referred?

Soldiers in front of the Pharmacy building

Photograph by Luigi Stironi, circa 1925

Soldiers in front of the French Bank of Syria

Photograph by Luigi Stironi, circa 1925

Selected literature:

Gelvin, James L. Divided Loyalties: Nationalism and Mass Politics in Syria at the Close of Empire. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Khoury, Philip S. Syria and the French Mandate: The Politics of Arab Nationalism, 1920-1945. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987.

Neep, Daniel. Occupying Syria under the French Mandate: Insurgency, Space and State Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Provence, Michael. The Last Ottoman Generation and the Making of the Modern Middle East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

The Routledge Handbook of the History of the Middle East Mandates. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2015.

MHS catalog records:

*The photographs were removed from the Sheldon Leavitt Crosby papers, and are now shelved and cataloged as the Sheldon Leavitt Crosby photographs.

“Light, airy, and genteel”: Abigail Adams on French Women

By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

When Abigail Adams arrived in France in August 1784, she must have felt like she had just landed on the moon. In all 39 years of her life, Abigail had never been south of Plymouth, north of Haverhill, west of Worcester, or east of Massachusetts Bay.

Twelve years earlier, Abigail wrote a letter to her cousin Isaac Smith Jr., who was traveling in London. She wanted to ask him “ten thousand Questions” about Europe. “Had nature formed me of the other Sex, I should certainly have been a rover,” she told him. Abigail explained to Isaac that it was too dangerous for a woman to travel alone and that by the time a woman has a husband with whom to travel, she also has a house to maintain and children to raise, creating “obstacles sufficent to prevent their Roving.” Already a mother of a 5-year-old, 3-year-old, and an 11-month-old, Abigail believed she had missed her chance to travel. “Instead of visiting other Countries; [women] are obliged to content themselves with seeing but a very small part of their own.” For these reasons, she told Isaac, “to your Sex we are most of us indebted for all the knowledg we acquire of Distant lands.”

One can’t help but wonder if Abigail remembered writing those words as her carriage bounced through the French countryside en route to her new residence in Auteuil, just outside of Paris. Whether or not she remembered that specific letter, she remembered the feeling of being stuck at home while her male relations traveled. She determined to write long, detailed letters to her female acquaintances, especially her nieces Elizabeth and Lucy Cranch, in an attempt to expand their worldview and to provide them with a female’s perspective of Europe.

In her letters to Elizabeth and Lucy, Abigail described the architecture of theatres, the designs of French gardens, and holiday customs. But John or John Quincy could have done that. That’s one of the things that makes Abigail’s letters remarkable—that she bothered to write to her nieces at all—something their uncle and cousin had largely neglected to do.

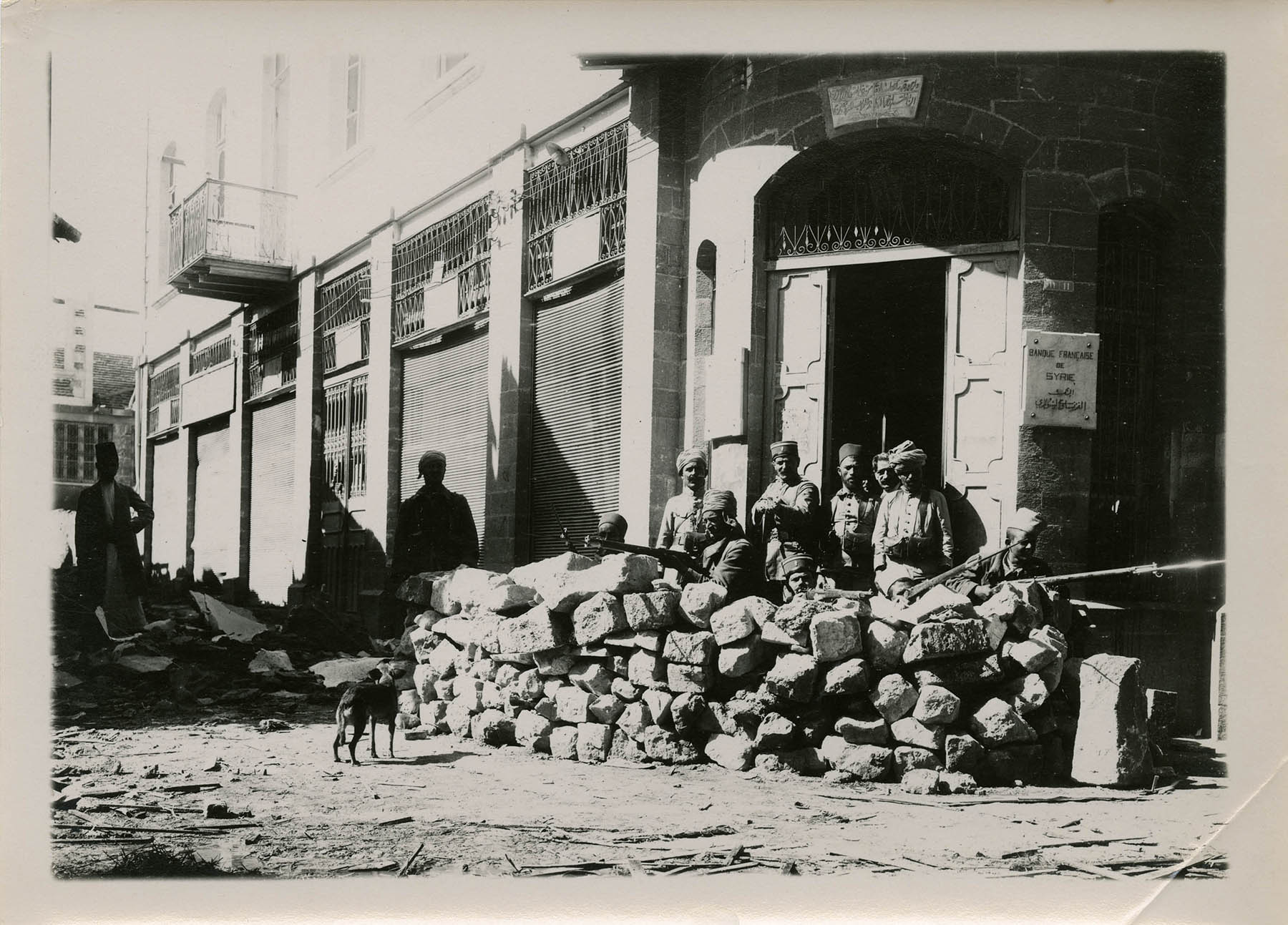

Left: Anne-Catherine de Ligniville, Madame Helvétius; Right: Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles, Marquise de Lafayette

Left: Anne-Catherine de Ligniville, Madame Helvétius; Right: Marie Adrienne Françoise de Noailles, Marquise de Lafayette

Travel books could describe architecture and provide maps, but there wasn’t one that provided a New England woman’s perception of French women. Though her correspondents entreated Abigail to divulge what French women were actually like, Abigail really only became acquainted with two women during her nine months in France—Dr. Franklin’s friend Madame Helvétius and the Marquise de Lafayette. The former “highly disgusted” her with her untidiness of dress and lewd manners; the latter charmed her immediately. When she arrived at the Lafayettes’ front door, “the Marquise. . .with the freedom of an old acquaintance and the Rapture peculiar to the Ladies of this Nation caught me by the hand and gave me a salute upon each cheek, most heartily rejoiced to see me. You would have supposed I had been some long absent Friend, whom she dearly loved.”

Unless she was with the Marquise, who spoke English well, Abigail felt isolated by her ignorance of the French language and took to observing rather than conversing. “It is from my observations of the French ladies at the theatres and public walks, that my chief knowledge of them is derived,” she explained to family friend Hannah Quincy Lincoln Storer. She accordingly described what French women communicated beyond words: “The dress of the French ladies is, like their manners, light, airy, and genteel. They are easy in their deportment, eloquent in their speech, their voices soft and musical, and their attitude pleasing.”

She observed to her sister Mary that “Fashion is the Deity every one worships in this country and from the highest to the lowest you must submit.” During her stay in Europe, Abigail mailed fashion magazines and patterns home so her friends could see what was a la mode and included silk or ribbons whenever possible so they could try the designs for themselves. She gave strict instructions, such as that “the stomacher must be of the petticoat color” and “gowns and petticoats are worn without any trimming of any kind.” Abigail added that Marie Antoinette had set the trend of “dressing very plain. . .but caps, hats, and handkerchiefs are as various as ladies’ and milliners’ fancies can devise.”

Marie Antoinette en chemise, 1783 portrait by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Marie Antoinette en chemise, 1783 portrait by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

Abigail never resigned herself to French attitudes towards sex and marriage, but she came to admire the easy elegance of French women and found herself missing them when she, John, and their daughter, Nabby, relocated to London in April 1785. She noticed that the English tried to copy French fashions but ended up “divest[ing] them both of taste and Elegance.” Abigail’s brush with European style convinced her that “our fair Country women would do well to establish fashions of their own; let Modesty be the first, ingredient, neatness the second and Economy the third. Then they cannot fail of being Lovely.”

George Hyland’s Diary, January 1919

By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

A new year means a new serialized diary here at The Beehive, where for the past four years we have showcased a diary from the collections written one hundred years ago (you can read the 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018 series in our archives!).

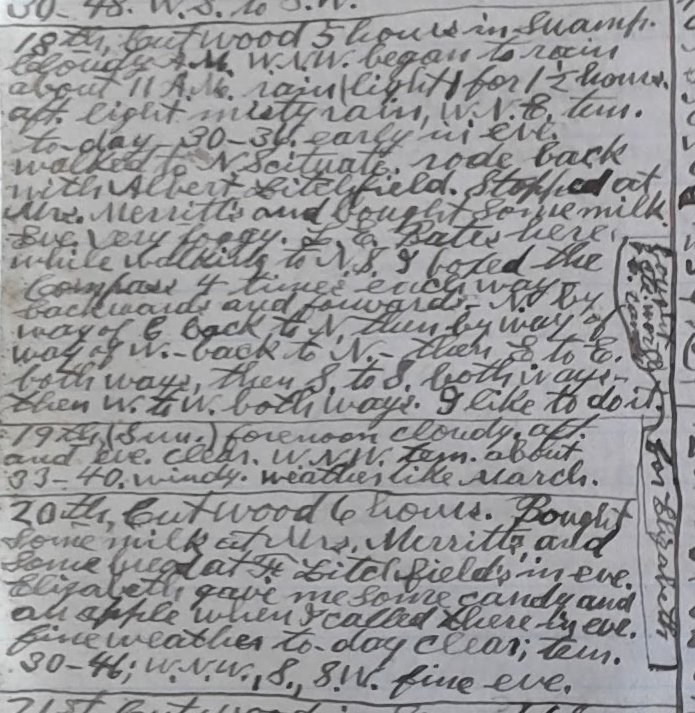

In October 1913 a fifty-nine year old man, George Hyland of Hingham, Mass., was given a hardbound standard diary by his representative to the Massachusetts state legislature, Rep. Charles H. Waterman. Rather than using the book as intended–filling one page per day for the year–Hyland instead began recording his life story in dense, script beginning with his childhood memories of the Civil War. Once he reached the present, Hyland continued to fill the diary until 1922, including the daily details of his life during the year 1919.

The year of 1919 opened “Cloudy. Cold. W.N.W. tem. about 25-36.” As you will see, the weather is a continual refrain in George’s diary — as you might expect for someone who spends his days outside chopping and hauling wood, walking to buy groceries, and visiting family. In order to make the most economical use of space in his diary, George abbreviates common words: “Staid [sic] all aft. ret. to N. S. on tr.” Stayed all afternoon, returned to North Scituate on train. We read about the price of milk (“now 12 cts per quart”) and the mundane tasks of life (“Mended some of my clothes in the eve.”) as well as entertainments (“Music by victrola in the sitting room.”) and tragedies: “A great mollasses [sic] tank exploded about 1 P.M. to-day on Commercial St., Boston.” We also get glimpses of the way in which the Great War continues to cast its long shadow even after the armistice. “Little Elizabeth,” George writes on January 21st, “came into the Swamp to tell me to come to the house and eat dinner. She is only 4 years old. She said her papa went to the war to fight the Germans and now he is dead.”

Join me in following George Hyland during one year of his life in the early 20th century.

* * *

PAGE 320

1919

Jan 1. Cloudy. Cold. W.N.W. Tem. about 25-36. Misty rain at times, very heavy fog all day. Eve warm, tem. 55 W.S.W. mod. Gale and rain — max. wind about 34 m.

2d. Mod. rain all day and eve. W.N.W. tem. About 36. Called at uncle Samuel’s late in aft. Lt. Weyland and Nellie G. Sharpe there, Elizabeth Bahe there, is to stay with Ellen at present.

3d. Rain all day and eve. W.N.W. to N.E. tem. About 27-32. Late in aft. Went to Lt. Weyland’s and bought a bus. of potatoes. Also bought some bread at H. Litchfield’s, then went to Mrs. Merritt’s and bought some milk. 10 P.M. snowstorm. W.N.E. Sawed some cedar logs in the cellar (some […] outlast winter) and put the wood in the back chamber — also put some planks and timbers there. Snowstorm all night

4th. Forenoon cloudy, aft. Clear. Tem. about 28-25, W.N.W. early in eve. Went to N. Scituate. Walked down and back. Stopped at Mrs. Merritt’s and bought some milk. Eve. clear. Cold. 3 inches of snow on the ground.

5th (Sun.) Clear. Cold. W.N.W. tem. 12-26 early in eve. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Staid [sic] there 1/2 hour. Music by victrola in the sitting room. Elizabeth sent me a cornball this aft. Eve. clear. cold; tem. 12. Got 2 sledloads of wood in Swamp this aft. Called at Uncle Samuel’s in eve.

6th. Light snowstorm early A.M. W.N.E. forenoon clou. aft. Par. clou. to clear. Tem, 26. Eve clear. W.N.W. tem. 7 P.M. 12. Got 2 sledloads of wood in Swamp. This aft. Called at Uncle Samuel’s early in eve.

7th. Light snowstorm early A.M. clear after 10 A.M. tem. About 18-38, W.N.W. in forenoon, S.E. in aft. N.W. in eve. Eve clear. Mended some of my clothes in eve. Called at Uncle Samuel’s later in aft. Elizabeth gave me a cornball.

8th. Clou. A.M. began to rain at 11 A.M. tem. 24-38. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s in eve. Clear in eve. W.W.N.W.

9th. Cloudy. Chilly. Damp. late in the forenoon walked to N. Scituate. Went to Hingham 12:17 tr. Went to Henrietta’s. Had dinner there. Carried a lot of toy furniture for her to sell for Henry. Staid [sic] all aft. ret. to N. S. on tr. at about 5:15 P.M. Walked home in eve. Brought my […] bag ([…]) full of clothes — coats, pants, etc. heavy to carry. Tem. to-day about 23-36. W. W. S. W. late eve. par cloudy. colder. very windy.

10th. Par. clou. to clear. W.N.W. and S.W. tem. 9-24. Called at Uncle Samuel’s in aft. Gave Elizabeth an orange and a bannana [sic] (Henrietta gave them to me yesterday). Got some wood in Swamp late in aft. Went to H. Litchfield’s and bought some bread early in eve. eve. clear. Cold.

11th. Split wood (very large pieces) 3 hours for Jane Litchfield. 75. Had dinner there. Early in eve. went back to N. Scituate. Walked down and back. Bought some groceries at Mr. Seavern’s store. Mrs. S. got […] for me also some chocolate candy (2 cts) for Elizabeth. Tem. 30-18. W.N.W. fair to par. clou. eve. cold. Tem. 9.

12th (Sun.) Clear. W.N.W. tem. 2-24. Eve. cold. clear. calm.

13th. Fine weather; clear; W.S.W. tem. 8-34. Fine eve. Got some dead wood in Swamp 1/2 mile from here to-day. Hard to get along there is so much dead wood piled up lying in all directions.

14th. Got some of my wood out of the Swamp (wet in Swamp to-day). Also cut wood 2 1/4 hours in Swamp for Uncle Samuel. He was cutting wood there. Cloud. Wind. S. to S.W. tem. 34-44. Early in eve went to N. Scituate. Bought some groceries at Mrs. Seavern’s store. Also bought some cold tablets for Ellen and some quinine (for toothache) for myself (1 doz 2 gr. Sulph Quinia pills – 15 cts). Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s — milk is now 12 cts per quart. Margaret Brown medicine for me at the Drug Store. Eve. clou.

15th. Cut wood 4 hours for Uncle Samuel. Cloudy A.M. 11 A.M. clear. W.N.W. tem. 32-42. Had supper at Uncle Samuel’s. Eve. clou. Fine weather

A great mollasses [sic] tank exploded about 1 P.M. to-day on Commercial St., Boston. 2,250,000 gallons ex. des. buildings, flooded street, k. 11 men, women, and children, and injured 60 others. Several horses k. 1 girl

PAGE 321

[cont’d] a. about 12 was drowned in the molasses.

16th. Cut wood 5 hours. Very fine weather. Clear. tem. 32-46 W.W.S.W. bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s early in eve. Fine eve. tem. 35. Weather is like early spring.

17th. Cut wood 6 hours. clou. A.M. Clear at 11 A.M. aft. par clou. to clou. a few drops of rain. 3 P.M. clear. eve. clear. temp. to-day – 30-48. W.S. to S.W.

18th. Cut wood 5 hours in Swamp. Cloud A.M. W.N.W. began to rain about 11 A.M. rain light for 1 1/2 hours. aft light misty rain, W.N.E. tem. To-day 30-36 early in eve. Walked to N. Scituate. rode back with Albert Litchfield. Stopped at Mrs. Merritt’s and bought some milk. Eve very foggy. L. E. Bates here while walking to N. Scituate. I boxed the compass four times each way – backwards and forwards – N. by way of E. back to N. – then by way of W. back to N. – then S. to E. both ways, then S. to S. both ways – then W. to W. both ways. I like to do it.

Bought 5 cents worth candy for Elizabeth.

19th. (Sun.) forenoon cloudy. aft. and eve. Clear. W.N.W. tem. About 33-40. Windy. Weather like March.

20th. Cut wood 6 hours. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s and some bread at H. Litchfield’s in eve. Elizabeth gave me some soure [sic] candy and an apple when I called there in eve. Fine weather to-day clear; tem. 30-46; W.N.W., S., S.W. fine eve.

21st. Cut wood in Swamp 6 hours. Had dinner at Uncle Samuel’s — little Elizabeth came into the Swamp to tell me to come to the house and eat dinner. She is only 4 years old. She said her papa went to the war to fight the Germans and how he is dead. (Was in the U.S. Navy). Elizabeth is Sarah’s third daughter. Cloudy. very damp to-day, W.N.E. and S.E. tem. 36-44. Very wet in the swamp. Eve. clou. W.S.E. will prob. Rain or snow to-night or to-morrow.

Last eve. (5-9 P.M.) I heard a great number of steamer whistles in Boston Harbor. [word] were saluting the Stm. “Canada” just arrived from France, with a load of soldiers. The whistling continued for 15 min.

22nd.Cut wood in the Swamp 6 hours. Finished cutting 2 1/2 cords of hardwood for Uncle Samuel. 625. Cloudy. Very damp. W.S. to S.W. tem. 34-46. Bought some choc. Candy for Elizabeth – 3cts. She came into the Swamp today. Eve. cloudy. 10:30 P.M., misty rain, W.W.

23rd. Cloudy. Foggy. W.S. tem 40-44. Got some wood in Swamp. In aft. Put rivet in a pair of scissors — also sharpened them — for Mrs. Merritt. 15. Late in aft. Went to N. Scituate. Bought some groceries at Mrs. Seavern’s Store. Also some choc. Candy for Elizabeth – 3cts. Walked down and back. Eve. clou. 9:30 P.M. began to rain. Rain all night.

24th. Cloudy to par. Cloudy. Very windy. tem. About 34-37 W. N.W. did some work at home. Early in eve. Went to H. Brown’s store. Wind blowing a gale – (40m.) Cold. Clear. Windy all eve. mod. At 11:50 P.M. much colder.

25th. Did some work at home. Very fine weather for […]. Clear; W.N.W; tem. 26-37. Paul Briggs […] home to-day – stopped here nearly 2 hours – had dinner here with me. He has been in the U.S. Army for one year and 4 months – has not had a furlough for a year – been on duty all the time — was in […]U.S. […] Guards — on duty at Jersey City, N.H. — pier 1 where the U.S. transports leave for […]. They had to guard the stores, supplies, and etc. He was discharged yesterday, and came from a Mil. Sta. in Pa. come on the 11:15 P.M. tr. from N.Y. last night had honorable discharge. The soldiers are coming home now as fast as they can get them here. Went to N. Scituate early in the eve. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Fine eve.

PAGE 322

[cont’d] Jan. 25. Paul brought home a box of fine cigars, which the capt. of his gave him. Paul gave me one of them (15 ct cigars). Paul was in the 16th Div. U.S. Army — Co. L. 302nd Inf. — but was transferred to Co. A. U.S. Guards.

Gave 25cts for [word] to soldier.

26th (Sun.) Clear; tem. about 26-40. W.N.W. eve. clear.

27th. Cut wood in Swamp 5 hours for Lt. Weyland. Fine weather. W. N.W., tem. about 28-40. Early in eve. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. Eve. par. clou.

28th. Sold E. Jane Litchfield 1 1/2 ft. of cedar wood for kindling. 150. Split it into very small pieces, also split some large pieces of hardwood, and housed the whole. 5 hours in all. 125. Had dinner there. Fine weather, fair to par. clou. tem. 32-40; W.N.W., N.E, S.E., S.W. early in the eve. Went to N. Scituate – bought some groceries at Mrs. Seavern’s Store – also some choc. candy for Elizabeth – 3cts. Rode 1 1/4 miles with George Hardwick in auto. Alma Lincoln and Irene Dalby brought a […] of Mt. Blue Spring water to E. Jane Litchfield late this aft. eve. clear but hazy at times. Stars look very small — will snow or rain soon.

29th. Light snow storm all day. W.N.E.; tem. 37. Cut wood in Swamp 1 hour in aft. Early in eve. Went to H. Brown’s store — also went to Mrs. Merritt’s and bought some milk. Eve. clou. 10 P.M. clear; W.N.W.

30th. Cut wood in Swamp 5 hours. fine weather, clear; tem. about 30-40; W.S.W. Snow nearly all melted today. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s in eve. Fine eve. clear. warm for season. W.S.W., by W.

31st. Cut wood 5 1/2 hours in Swamp. Clear, windy. (M.W.) tem. 28-40. Cold late in aft. and in eve, windy early in eve. Bought some milk at Mrs. Merritt’s, also got some for Ellen, then went to H. Litchfield’s and bought some bread. Cold night.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original. The catalog record for the George Hyland’s diary may be found here. Hyland’s diary came to us as part of a collection of records related to Hingham, Massachusetts, the catalog record for this larger collection may be found here.

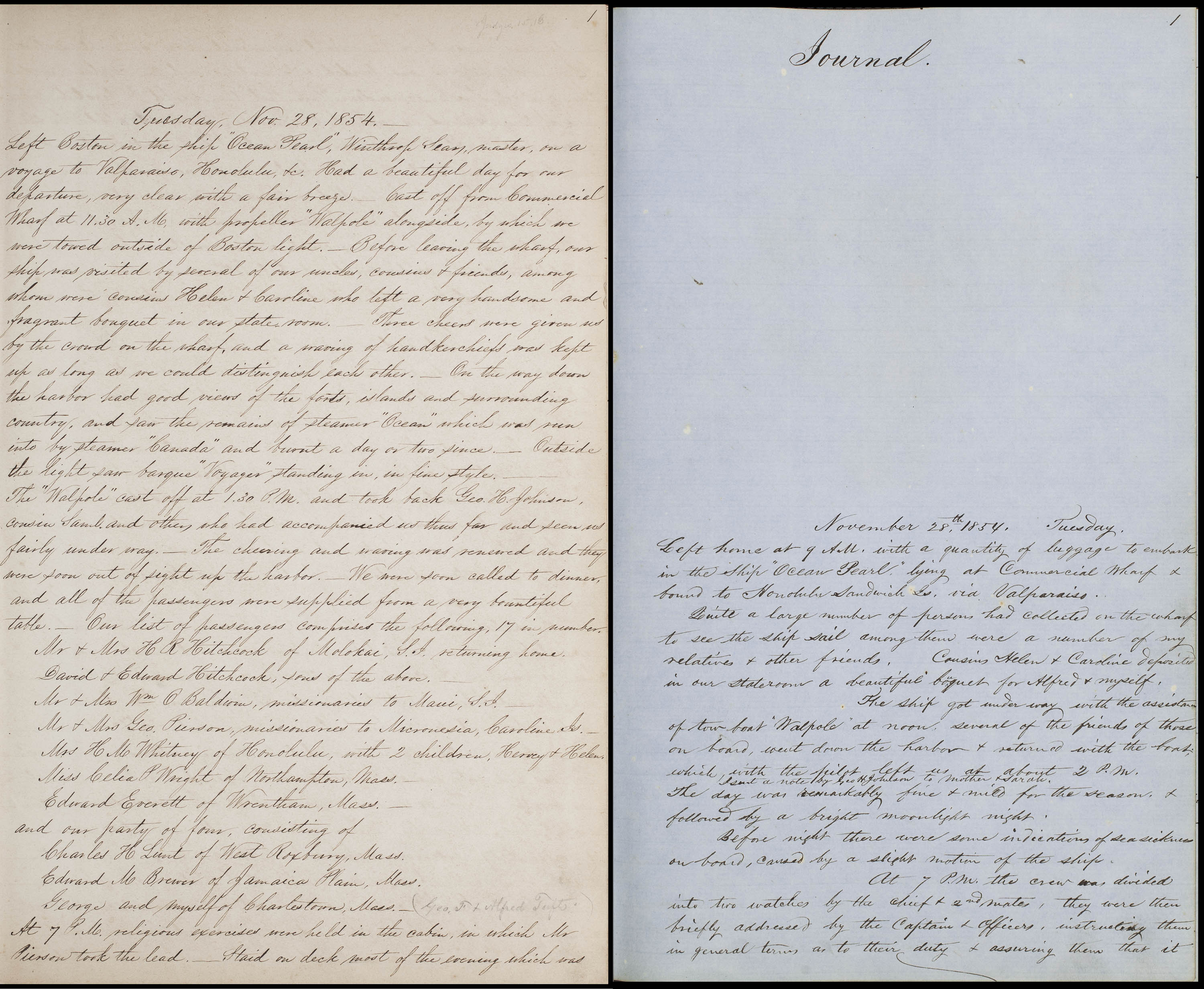

New and Improved: The Tufts Family Logbooks

By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

My work as a processing archivist here at the Massachusetts Historical Society involves not only cataloging new manuscript collections, but also improving descriptions and access for collections that have been sitting on our shelves for some time. Case in point: the Tufts family papers, which was recently brought to my attention by Laura Wulf, the MHS’s photographic and digital imaging specialist. While working on digital images from that collection, she noticed an oversight in our online catalog ABIGAIL.

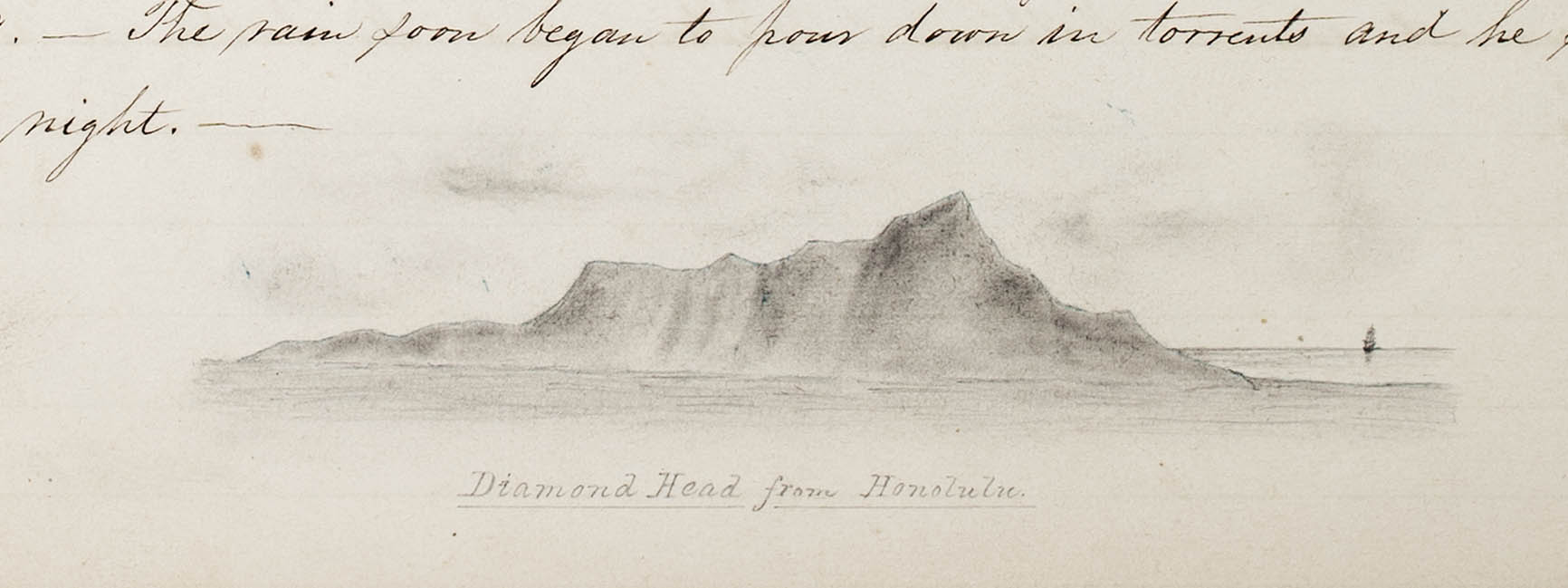

The collection consists of correspondence, diaries, logbooks, and other papers of the notable Tufts family of Charlestown, Mass. Included are two logbooks dating from the mid-1850s, kept by brothers George and Alfred Tufts. Normally, logbooks that are part of a larger collection are individually cataloged to allow for more detailed subject access. As Laura discovered, Alfred’s had been cataloged, but George’s was nowhere to be found.

The oversight was understandable—the brothers were actually traveling together on the same ship, the Ocean Pearl, and it’s pretty easy to make a mistake about who kept which volume if you don’t have time to examine them closely. But George deserved his due, and I was sorry to see him overshadowed by his younger brother like that! So the first thing I did was create a new, separate catalog record for his log.

The oversight was understandable—the brothers were actually traveling together on the same ship, the Ocean Pearl, and it’s pretty easy to make a mistake about who kept which volume if you don’t have time to examine them closely. But George deserved his due, and I was sorry to see him overshadowed by his younger brother like that! So the first thing I did was create a new, separate catalog record for his log.

I enjoy doing this kind of clean-up, not only because it makes our catalog more useful and our collections more discoverable for researchers, but also because it gives me the opportunity to add more detail to ABIGAIL and to familiarize myself with our older collections. The Tufts family papers were donated to the MHS back in 1962, and I don’t think I’ve ever had reason to look at them before. It’s a really fun and interesting collection.

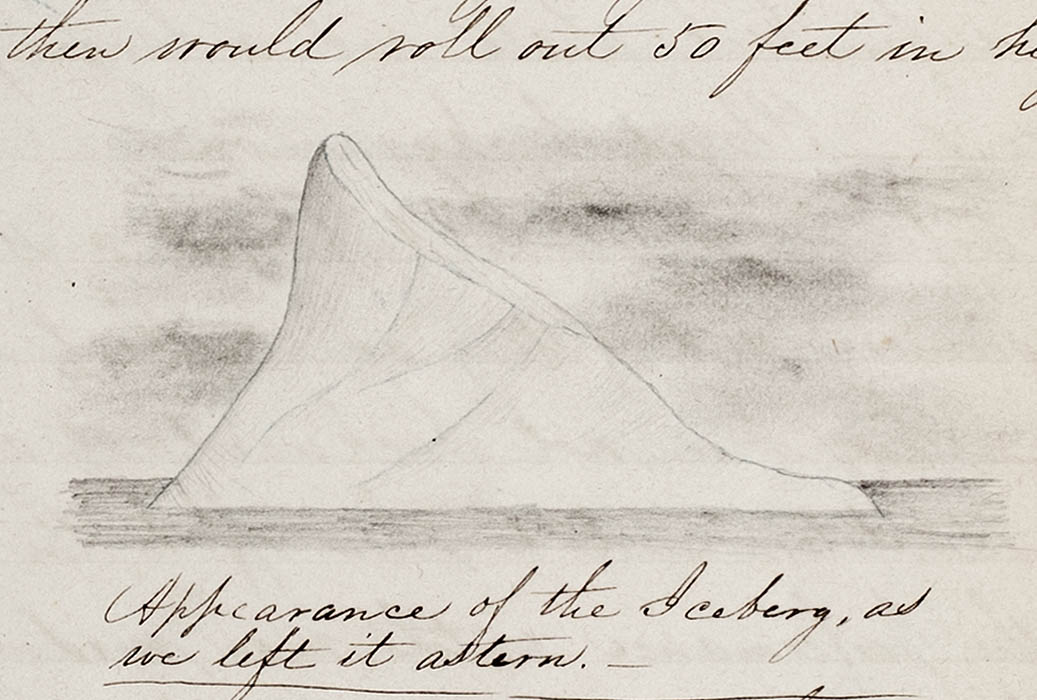

In their logbooks, George and Alfred kept the usual navigational records—longitude, latitude, wind, course, temperature, etc.—but they didn’t stop there. The logs are also journals, fleshed out with long-form descriptions of daily life on a ship, including who got seasick (George), who lost his hat overboard (Alfred), who got drenched (pretty much everybody at some point), what Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin were arguing about (the window shutter), and what was really going on between Capt. Sears and Mrs. Whitney (who knows?). The two volumes complement each other; the brothers recount the same events, often in very similar language, although Alfred’s entries tend to be longer. Both logs also contain sketches of icebergs, islands, and other sights.

The Ocean Pearl sailed from Boston on 28 November 1854, around Cape Horn at the southern tip of South America, and landed at Honolulu, Hawaii. There, it turns out, the brothers split up—Alfred continued on the Ocean Pearl to the Far East, but George stayed in Hawaii for six months, where he wrote terrific descriptions of the islands’ natural and cultural wonders. On 26 September 1855, George embarked for San Francisco, overlapping with the tail end of the California Gold Rush, then sailed across the Pacific to Hong Kong and other points in Asia. Adding insult to injury, these voyages had been mistakenly attributed to Alfred, too!

After straightening out the catalog records for both logbooks, I noticed the collection contained another journal kept by George in 1850. On closer inspection, I found it described a trip up the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers via steamboat, so I added some detail to that catalog record, as well. Like the logbooks, there’s a lot more to this volume than meets the eye. For example, here’s one of George’s entries from June of that year:

In the afternoon went in a canoe to Crow wing village 6 miles below St Paul. I had seen the indians among the whites, but here they were by themselves on their own soil doing things in their own way. When I arrived at the village they had just been dancing the scalp dance, over the scalps they had taken this spring from the Chippeways. When the scalps were taken they made a mark on the knee & are to dance every other day till the grass gets to that height. A group of them were sitting on the ground playing a game with moccasins accompanied with singing, drumming & yelling with “variations.” I heard their noise when two miles from the place. Their burial ground is on a hill back of the town. The bodies are mounted on a scaffold with the articles used by the deceased in his life time hanging about it. Also the clothing & locks of hair. They leave them in this way about 6 weeks & then bury them.

High-quality digital images of the Ocean Pearl logbooks of George and Alfred Tufts, as well as material from related collections at the MHS and other repositories, are available as part of the China, America and the Pacific online resource, published by Adam Matthew Digital. You’ll have to visit our library in person (or another participating library) to use this subscription database, and we hope you will. If you have questions about any of our collections, please don’t hesitate to contact our reference staff.

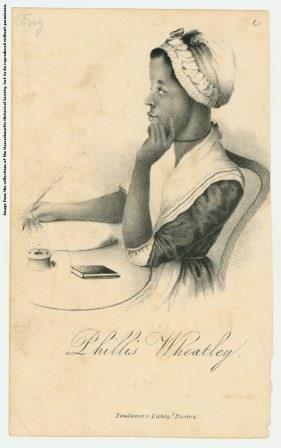

The First Publication of Phillis Wheatley

By Daniel T Hinchen, Reader Services

Recently, the MHS hosted a program called “No more, America,”* which featured a conversation with Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Peter Galison, both of Harvard University. In it, the two men reimagined a 1773 debate between graduating Harvard seniors Theodore Parsons and Eliphalet Pearson who deliberated on the compatibility of slavery and “natural law.” In the program, Gates and Galison added a third contemporary voice to the argument, that of the then-enslaved Phillis Wheatley, the acclaimed poet who lived just over the Charles River from the two Harvard students.

Now, just over a week later, we recognize the anniversary of the first publication of one of Wheatley’s poems. “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin” appeared on December 21, 1767, in the Newport Mercury, a Rhode Island weekly newspaper. According to Vincent Carretta in his 2011 biography of Wheatley, this poem was not published again during Wheatley’s lifetime.

When Wheatley submitted her poem to the Newport Mercury, she addressed a note to the printer which was to precede the poem.

Please to insert the following Lines, composed by a Negro Girl (belonging to one Mr. Wheatley of Boston) on the following Occasion, viz. Messrs Hussey and Coffin, as undermentioned, belonging to Nantucket, being bound from thence to Boston, narrowly escaped being cast away on Cape-Cod, in one of the late Storms; upon their Arrival, being at Mr. Wheatley’s, and, while at Dinner, told of their narrow Escape, this Negro Girl at the same Time ‘tending Table, heard the Relation, from which she composed the following verses.

On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin

Did Fear and Danger so perplex your Mind,

As made you fearful of the Whistling Wind?

Was it not Boreas knit his angry Brow

Against ? or did Consideration bow?

To lend you Aid, did not his Winds combine?

To stop your passage with a churlish Line,

Did haughty Eolus with Contempt look down

With Aspect windy, and a study’d Frown?

Regard them not; — the Great Supreme, the Wise,

Intends for something hidden from our Eyes.

Suppose the groundless Gulph had snatch’d away

Hussey and Coffin to the raging Sea;

Where wou’d they go? Where wou’d be their Abode?

With the Supreme and independent God,

Or made their Beds down in the Shades below,

Where neither Pleasure nor Conten can flow.

To Heaven their Souls with eager Raptures soar,

Enjoy the Bliss of him they wou’d adore.

Had the soft gliding Streams of Grace been near,

Some favourite Hope their fainting hearts to cheer,

Doubtless the Fear of Danger far had fled:

No more repeated Victory crown their Heads.

To see what materials the MHS holds related to Phillis Wheatley’s life and work, you can search our online catalog, ABIGAIL, then consider Visiting the Library, but be sure to consult our online calendar for upcoming holiday closures.

*Watch a recording of the event that took place at the MHS on 12 December 2018.

References

Carretta, Vincent, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage, University of Georgia Press, 2011.

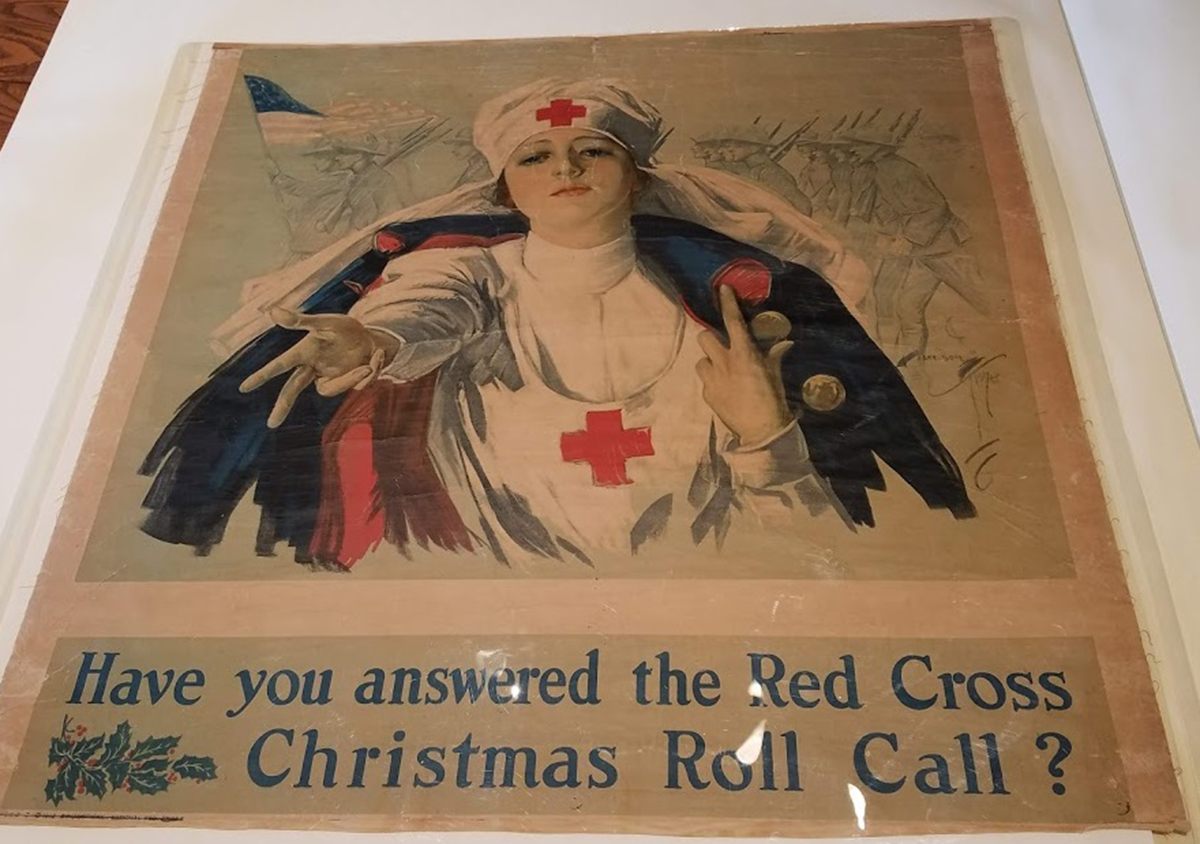

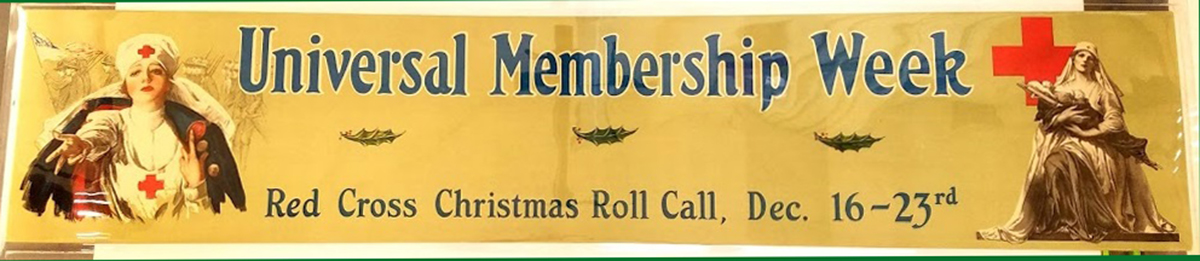

Christmas 1918

By Rakashi Chand, Reader Services

Christmas of 1918 should have been jubilant–the war was over, soldiers were starting to come home and women were on the verge of gaining suffrage. But sadly, dark shadows loomed over festivities and revelry that year, as the aftermath of the war and the widespread Influenza and tuberculosis left hundreds of thousands dead, sick or wounded. The Nation’s central relief organization was the American Red Cross, which desperately needed funding, so they launched a membership drive called the ‘Christmas Roll Call’ from 16 through 23 December, 1918.

“When the United States entered the World War the people appointed the Red Cross as its steward to minister to the wants of human beings in distress whenever aid and succor were needed.

… This is in brief the service work of the Red Cross expressed in unemotional statistics. The real work of aiding suffering humanity, of nursing the ill, and ministering to those in want – the service of relieving the worries of our men overseas- the thousand and one things done in a day’s work- all that can not be told in numerals.

But to continue this work for humanity, to serve as steward for the American people, will require the united support of all Americans. With this end in view, the Red Cross will hold it’s second annual Christmas Roll call during the week of December 16 to 23rd, when it is hoped that every one will renew the nation-wide pledge of last year to uphold the flag – a vow taken by 22,000,000 million adults and 8,000,000 children.

Some day, and that day seems near at hand, the world will wish to spend as much effort and gold for the prevention of war as it does now for the amelioration of its infinite ills. At this hour, however, the American Red Cross is the sacrament oT the nations, the visible expression of the mother-heart of the race, the beacon and the hope of the world’s wounded and storm-tossed everywhere. Membership in the American Red Cross defines and honors the members and scatters healing where healing is sorely needed.” said the Advocate of Peace in December of 1918.

The Broadsides created to promote the ‘Christmas Roll Call’ or Membership drive of 1918 are some of the most beautiful pieces of 20th century ephemera. The MHS houses some of the famous broadsides (or posters) created for the Roll Call. The posters’ popularity eclipsed the roll call itself–they are perhaps the most beautiful images ever associated with the Holiday Season. The artists that created these images were some of the best of the time, working pro-bono for the Red Cross effort, such as Harrison Fisher, who created a new stereotype for American woman as bold and beautiful, known as the “Fisher girls.

Christmas a century ago reminds us to be thankful for our blessings, and to continue to support those who work tirelessly to end suffering and alleviate pain, towards the betterment of all humans and life on this shared earth.

The MHS will be closed from 24 December through 1 January, but we welcome you to visit the Library during regular hour through Saturday, December 22nd to enjoy exploring our collections including our wonderful Ephemera collection of broadsides, posters and greeting cards.