by Caroline Culp, Stanford University, Andrew W. Mellon Short-Term Research Fellow at the MHS

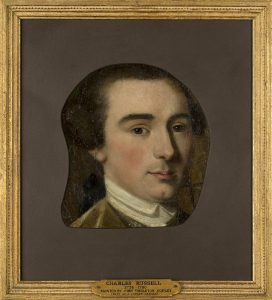

There is a curious, even eerie painting in the Massachusetts Historical Society’s collections. The remnant of a larger canvas, Charles Russell’s disembodied head floats as if suspended in its adopted gold frame. So many of the standard questions scholars lob at portraits fail to stick to Russell’s image—How does the sitter’s pose reflect his identity? How does his clothing mark his social rank? How do the objects surrounding him speak to his historical moment?

None of these questions can be answered. Instead, the repeated drumbeat of one query sounds: why and how did this cut-out face survive?

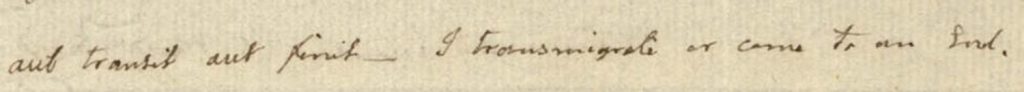

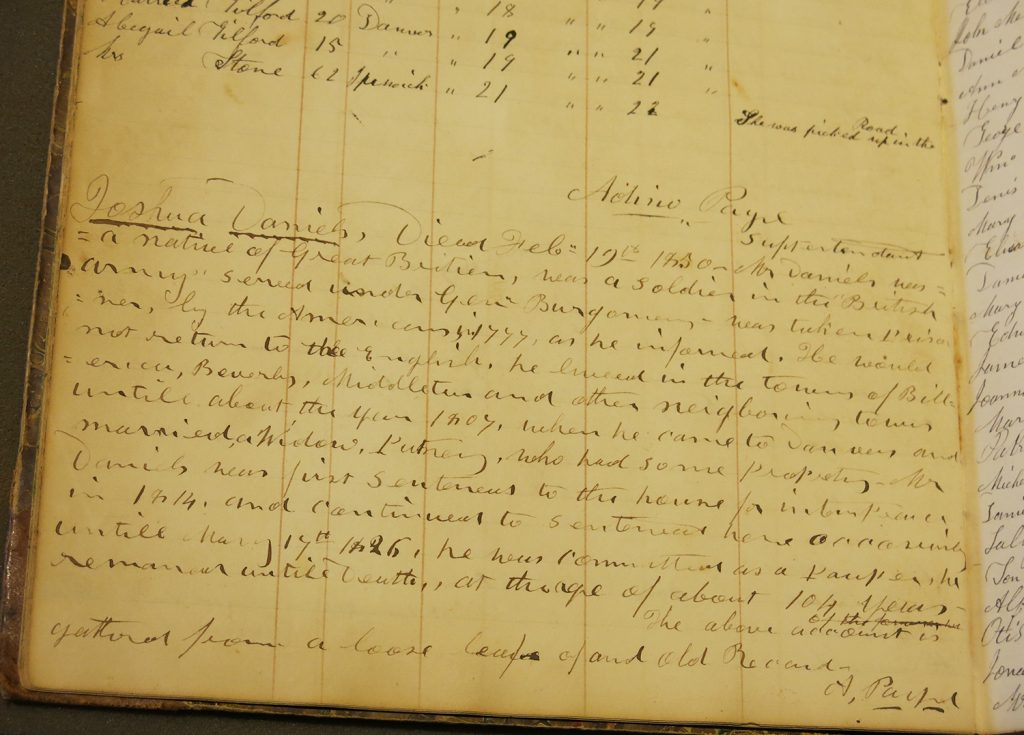

Charles Russell was painted by John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), colonial America’s preeminent artist. Perhaps the work was completed in 1757, on the occasion of Russell’s graduation from Harvard. A loyalist, Russell fled to Antigua in 1774, where he died six years later. His portrait remained in the care of his sister, Sarah Russell, until her death in 1819, when it should have been inherited by Charles Russell’s eldest daughter, Penelope Russell Sedgwick.

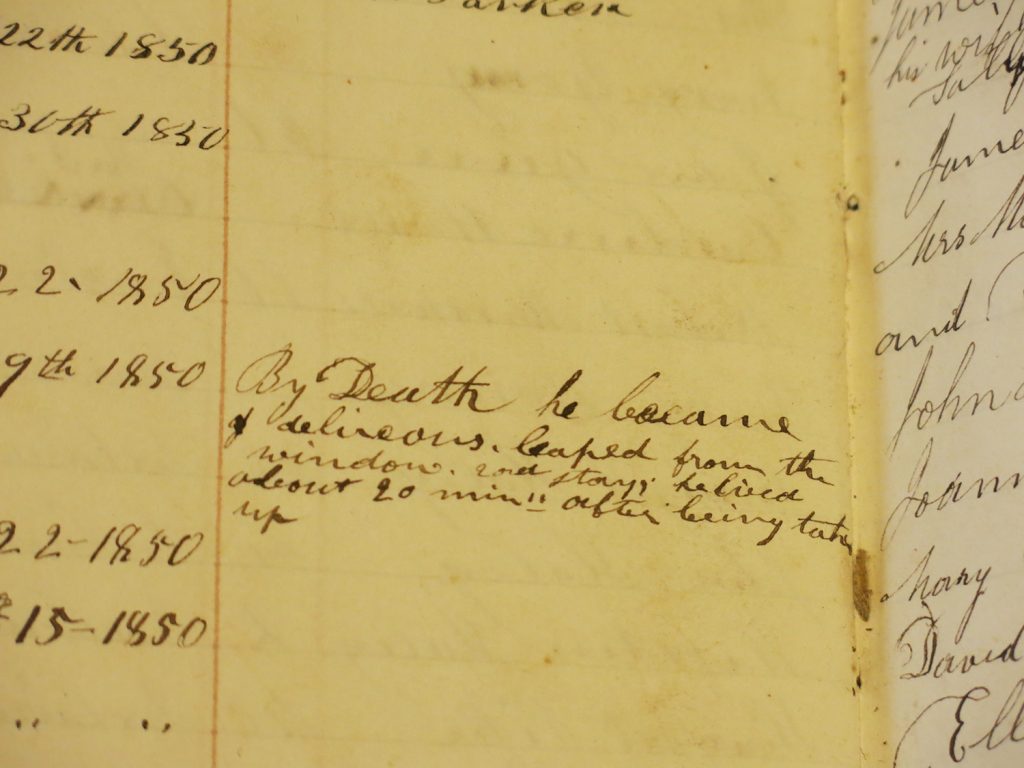

But according to family ledged, Penelope’s sister Katharine Russell was so distraught at not herself receiving the picture of her father that “she cut out the head with a pair of scissors, and concealed it in her pocket” where she “always carried the head cut from the portrait.” In the pocket it remained for nearly thirty years, until “shortly before her death in 1847 she sent for her cousin, confessed to her what she had done, and gave her the head.” For almost a hundred years afterward the fragment was passed down the female line of the family until Mary Curtis donated it to the Society in 1943.[1]

This startling tale of family jealousy, desire, and destruction reveals Katharine Russell’s deep fetishization of her father’s portrait. It is a story that calls us to re-imagine all those heritage portraits hanging silently above the fireplace of American history.

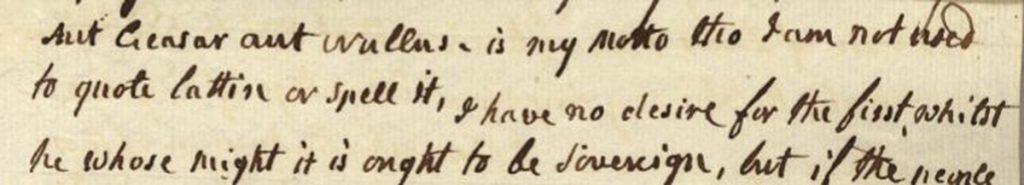

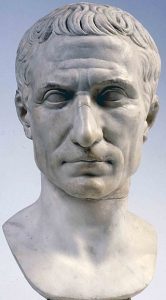

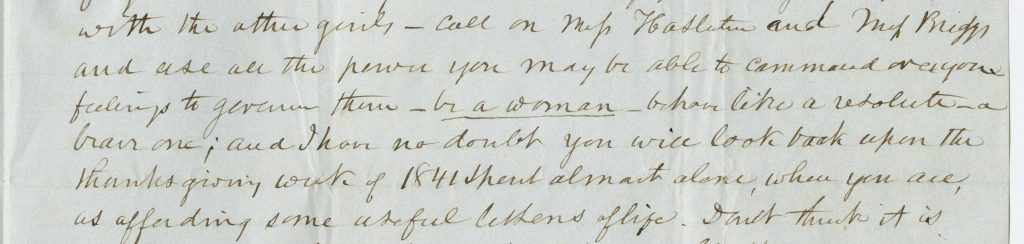

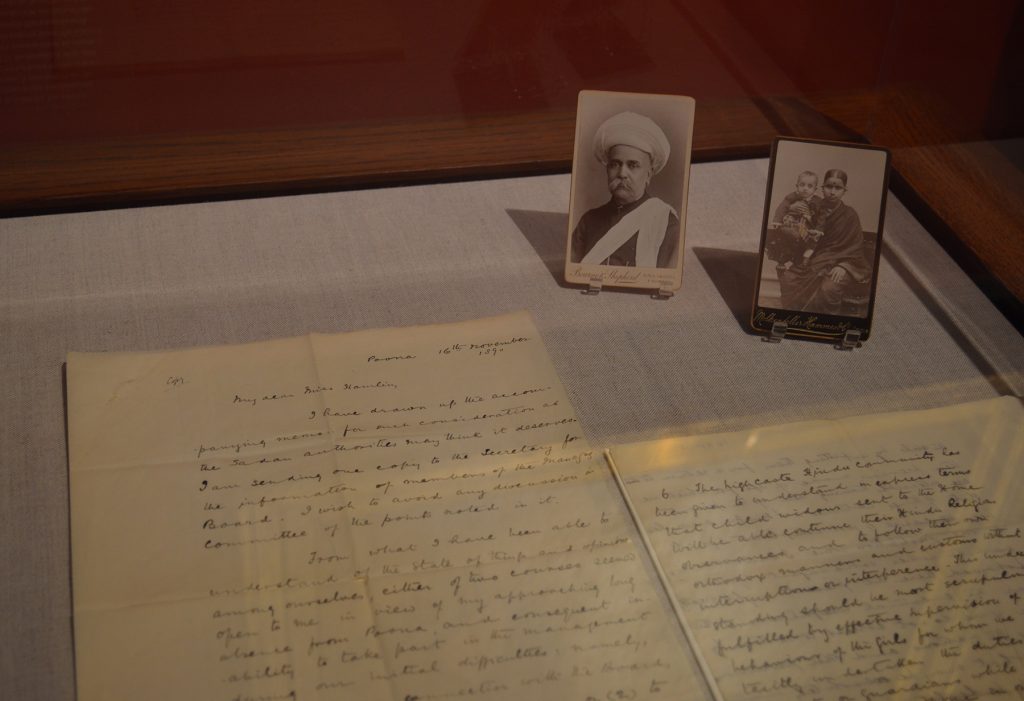

In the 19th-century Atlantic world, a portrait was no mere silent witness to domestic drama. It was often a personified presence, activated by the mind’s desire for connection. A set of Copley family letters in the MHS collections illustrate the role a portrait could play within the home. Years after the painter left revolutionary Boston for London, his daughter Elizabeth (called Betsy) married and returned to America. Letters between Betsy and her sister Mary vowed that Betsy’s “absence will never lessen our mutual attachment.” Please, Mary begged, “dear Sister write to me as frequently as you can, as that alone can alleviate the pain of separation.”[2]

It was Betsy’s portrait that lessened some of the heartbreak the Copleys left in London felt at her leaving the household—and the hemisphere. John Singleton Copley painted Betsy shortly before her departure, capturing her with dreamy directness, her mouth half open as if about to speak. Though her dress and background fade into incompleteness, the crisp strokes of her face look ahead to the “immense distance [that] will be between us.” Betsy’s portrait was touted as “perfectly satisfy[ying]” to the family, who were “quite in raptures” with this surrogate presence that came to represent her absence.[3]

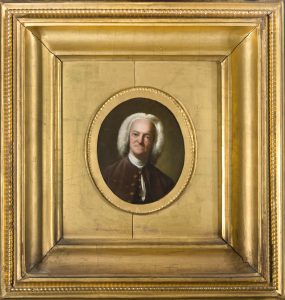

Today, Copley’s fragments of the past continue to have a presence among the living. Anne E. Bentley, Curator of Art & Artifacts at the Massachusetts Historical Society, welcomes incoming staff members with: “Let’s see if we can find you a nice office mate.” New staffers may select a work of art from the Society’s collections to hang in their personal office—a work that would otherwise be languishing off view in the shadows of storage. Bentley helps MHS historians to find a fitting “office mate” to share their space and inspire their work. It is this practice that allows Copley’s miniature portrait of Samuel Danforth to retain the integrity of its original use. Looking out affably from his gilded oval frame, Danforth’s image from the 18th century continues to be comfort and company in the 21st. Would that we could all have “someone to live with” at work.[4]

[1] All quotations copied from a letter given by the donor, Mary Curtis, when she donated the fragment to the MHS in 1943. See Andrew Oliver, Ann M. Huff, and Edward W. Hanson, Portraits in the Massachusetts Historical Society: An Illustrated Catalog with Descriptive Matter (Boston: The Society, 1988): 87.

[2] Mary Copley to Elizabeth Copley Greene. August 23rd, 1800. MHS MS N-1034, Box 1.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Quotations derive from email correspondence with Anne Bentley and Katy Morris, April 5, 2019.