By Anna Clutterbuck-Cook, Reader Services

Today, we return to the diary of George Hyland. If this is your first time encountering our 2019 diary series, catch up by reading the January, February, March, April, and May 1919 installments first!

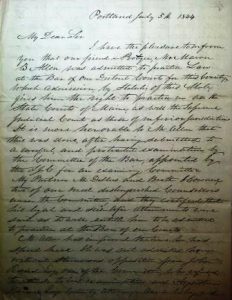

Early in June, George moves house from his winter quarters to “the James place” he mentions paying $800 to rent in the entry for May 28th. It is unclear from the diary whether George considers this move a temporary or more permanent one, although he notes on June 27th that “Mr. James is coming back from Oregon and will live here,” followed up two days later with the note, “I do not know where I shall go.”

As with previous months, George records the hours he spends at various tasks for neighbors and the money owed (presumably striking the numbers out when he is paid). A new leisure activity appears in the diary for June: time spent nearly every evening playing the guitar. Food also makes its appearance: rhubarb sauce, peach preserves, doughnuts, baked beans, berry cake, and moss pudding. If you — like I — have never heard of “moss pudding” before (see entries for June 13-14) it seems to be a milk pudding with a type of coastal seaweed used to thicken the mixture. Edible Cape Cod provides a recipe.

On June 29th George breaks his daily record to insert a paragraph on the Treaty of Versailles (signed on June 28th, 1919) which in George’s words: “closes the greatest war the world has ever known.” The next day, he returns to mowing the lawn “with the sickle and shears.”

Without further ado, here is George Hyland’s June 1919 in his own words.

* * *

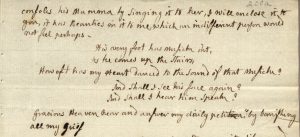

PAGE 332 (cont’d)

June 1. (Sun.) fair, W.N.E., S.E. Eve. par. Clou.; W.S.W. Went to H. Litchfield’s late in eve. To buy some bread.

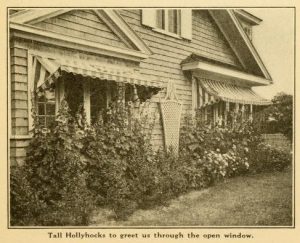

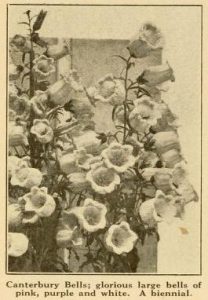

2d. Went to the James place and worked 7 hours — mowing grass and making flower gardens and transplanting foxglove, can. bell, hollyhock, heliopsis and larkspur and cornflower plants — carried them there from my garden this A.M. Ellery B. Hyland went there with me in auto, carried some plates, dishes, etc. Had my dinner in the house — bought it in store. Ret. — rode 1 1/2 miles with Albert Litchfield. Fine weather, W.S.E. Clear. Nellie B. Sharpe stopped to see my plants. I watered all of them well.

3d. Went down to the James place — mowed and trimmed all around the house. Carried my dinner. Walked down. Ret. — rode 1 mile with Ellery Hyland in auto. Carried some foxglove and canterbury bell plants and gae them to Mrs. Emma F. Sargent. […] Very hot weather W.W.S.W.; tem. 70-98 nearly all day.

4th. Moved into the James house. Ellery Hyland carried my things there in his auto truck. I rode down with him. 2 loads. Very hot weather – tem. 96. W.S.E. Clear. Worked in the place – made gardens for the plans I carried there.

5th. Worked 4 1/2 hours for Mr. S. T. Sheare clearing out the big store. Carried rubbish to the dump near Bound Brook and put the broken boxes […] his cellar. Very hot weather — tem. 78-98; W.N.W. fine eve. Mrs. Ethel Torrey and Margaret Sheare, and Mrs. Torrey’s children called here early in eve. Played on the guitar 3/4 hour in eve. X 1.35.

[entry crossed out]

6th. Worked 7 hours for Mr. Speare — repairing side-walk. 2.10. Fine weather. W.N.W. tem. 65-83. Walter Sargent [phrase crossed out] called here early in eve. I showed him a birds nest in the large rose bush on the south side of the house – 4 young birds (sparrows) in it. Played on the guitar 3/4 eve.

7th. Worked 8 1/2 hours for W. and Mrs. Emma Sargent. 2.40. Mrs. Sargent gave me rhubarb sauce — in a tumbler, and at night gave me some baked beans and cake to take home. Thunder, tempest 6 P.M. just as I finished work. Squall — W.N.W. Thunder storm and rain all eve. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve. tem. To-day 66-84. Muggy.

8th. (Sun.) Cold. W.N.E. tem. 55. Mrs. Irene E. Litchfield spent eve. Here.

9th. Worked on the place — dug up garden and did other work. Cold. Cloudy in afternoon — rain at times all aft. and eve. tem. 51-53. W.N.E. Played on the guitar 1/2 hour in eve.

10th. Fine weather. Cool; W.S.E. Clear. Planted my garden — called at Charlie’s late in forenoon — had dinner there. He cut my hair. Eve. clear. Cold. tem. 54. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve.

11th. Worked 6 1/2 hours for Miss Margaret Speare repaving side walk. 1.80. Fine weather, W.N.W. Clear. Cool. Walter Sargent, Mrs. Emma Sargent and Mrs. Edna Bailey called here late in […]

PAGE 333

to see my flower gardens. Mrs. Bailey is Mrs. Sargent’s mother. I showed Mrs. Sargent the birds nest in the great rose bush but the birds had left it. Mr. and Mrs. Sargent will leave here for Chicago Ill. where they will spend the summer, they have let their home here. Called at Wesley Gardner’s in eve. (about 5 P.M.)

12th. Worked on sidewalk 6 hours for Mr. Sheare – 1.80. Cool. W.N.E. Clear. The piano that was in the N. room was moved from here to Mr. Sheare’s store — Girl Scouts had it loaned to them. Miss Eudora Bailey and Miss Norma Morris came here when the piano was moved. Eve. clear. Cold. tem. 45. W.N.E. Fine weather.

13th. Went home to get some of my things. Called at Mrs. Harriman’s 1 3/4 hr. I also called at Uncle Samuel’s. Gave Mrs. Harriman 4 foxglove plants from my garden. Bought 1 1/2 qts. of milk at Andrew Bates’ then went back to James place. Worked on my garden 4 hours. Also late in aft. hoed in garden 2 hours for Archie Torrey — 60. Walked home and back. Played on the guitar 1/2 hour in eve. Fine weather. Clear. W.S.E. Cool. Made moss pudding.

14th. Hoed gardens 7 hours for Archie Torrey and S. T. Speare — 2.10. (Mr. Sheare is Mrs. Torrey’s father live in the same house). Mrs. Ethel T.gave me 2 doughnuts. Fine weather tem. 55-75. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve. W.S.E. to-day.

15th. (Sun.) Fine weather. W.S.E. tem. 65-86. Went home to get some of my things. Walked there rode nearly back with Charlie […] in auto. Bought some mill at Mrs. Merritt’s. Got 4 foxglove plants at home — gave them to Mrs. Edith Sargent and transplanted them for her. Lives with Mrs. Bailey — in house off James place — is Walter Sargent’s sister. Made a moss pudding in eve.

16th. Worked 7 1/2 hours for Peter W. Sharpe — had dinner and supper there. Nellie did go to school to-day. Fine weather. W.S.E. Charles spent eve. Here — I played on the guitar 1 1/2 hours. Fin. planting my garden early this eve. 11 P.M. clear.

17th. Worked 6 1/2 hours for P.W. Sharpe. Had dinner there. Fine weather — clear. W.S.E. worked 3 hours on the James place — after supper. Played on the guitar 1 hour late in eve.

18th. Worked 6 hours for P.W. Sharpe. 18 hours in all — 4.50. Had dinner there with Mrs. S. Fine weather. Cool. Clear. W.S.E. Worked 2 hours in my garden early in eve. Played on the guitar 1 hour late in eve.

19th. Mowed and trimmed lawn and bank 3 hours for Mrs. Eudora Bailey. Mrs. Sarah Brown (nee S.T. Bailey) there to-day. Have not seen her before for 16 or 17 years. Mrs. Bailey’s birthday to day (age 79 all her children called except Mrs. Emma F. Sargent — she is in Chicago Ill.) Henry, Albert, Fred, and Sarah. (Fred (ten), Henry (bass), Emma (sop.) and Sarah (contralto) are the Bailey Quartet. Sarah told me she lives in Wollistan, Mass. I also mowed grass 3 1/3 hours for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns. In eve. stopped and talked nearly an hour with a young man in an automobile near the fountain in N. Scituate — he brought some people from Thomas W. Larvson’s place to attend the motion pictures at the Victoria Hall near here. He was in the late war in British Army — was wounded 2 or 3 times while in service. He told me that Miss Jean Larvson was to be married to-night. Weather to-day W.S.E.; tem. 60-84; clear. Eve. clear. Chilly. Damp.

20th. Worked 5 1/2 hours for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns — mowing and other work. Rain 12:30-1:30 P.M., then cloudy. Eve. cloudy. 11 P.M., clear. Played on the guitar 1 1/4 hours in eve.

21st. Worked 6 hours for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns — haying and mowing lawn — 14 1/2 hours in all — 3.35.Also mowed the grass among Mrs. Eudora Bailey’s currant bushes — 1 hour. Fine weather. W.N.W., tem. 65-85. Lightning S. of here in eve. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve. 11 P.M. clear.

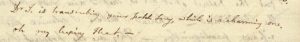

22nd (Sun.) Fine weather — over —

PAGE 334

June 22. [cont’d] Clear. Cool. W.S.E. Cleared up a great pile of rubbish back side of the house. Eve. par. Clou. 11 P.M. clear.

23d.Worked haying 1 ½ hours — 45 — for Mrs. M. G. Seaverns. Also worked on the front steps — on this place — 7 hours. Par. cloudy, W.N.W., S.E. Played on the guitar 1 hr. 10 min. In eve. tem. to-day 50-67.

24th. In forenoon worked on the front steps and wooden walk. In aft. went to Hingham on train. Walked to Henrietta’s (H. Cen.) had dinner there. Spent aft. There. Ret. — rode back with H. Frankland his wife and three children, Ethel and Henrietta in automobile — they went to N. Scituate beach. Very hot weather — tem. 69-96. — 96 in shade all aft. Mrs. Ethel Torrey and children called here late aft. About 7:30 P.M. (fast time — 6:30 P.M. Standard Time). I went back with them to see their gardens. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve.

25th. Worked 2 1/2 hours for Mrs. M.G. Seaverns haying — got in all the hay. 75. Also worked on the steps and walk — finished the steps and walk. Also mowed with lawn mower, sickle, and shears 7 hours. Hot weather — tem. 68-94. 94 all aft. Played on the guitar 3/4 hour late in eve.

26th. Mowed the grass with lawn mower, sickle, and shears on the whole place — also repaired a window and the roller on the well curb — so it would not slip when drawing water — handle turn-in rolled — it turned in the roller a few days ago and it hit my right arm 6 or 7 times before I could get out of the way of it. Par. clou. tem. 65-85. W.S. transplanted some summer turnips late in aft. Mason Litchfield called here early in eve. — to get me to mow their lawn. I played several selections on the guitar for him. Late in eve. played on the guitar 1 h. 35 min — played 2 hours in all this eve.

27th. Mowed and trimmed lawn 5 hours for Mason Litchfield. Clou. Very warm and muggy — light rain at times. Began to rain at 3 P.M. and rained all aft. and eve. Mrs. Eudora Bailey came here about 6:30 P.M. with 2 berry cakes — she made them. She is 79 yrs of age. Played on the guitar 1 hour in eve. I have got to move from this place Mr. James is coming back from Oregon and will live here.

28th. In forenoon — trimmed grass around the place 1 hour for Mason Litchfield — 6 hours in all — 1.75. In aft. Worked on the front walk 1 3/4 hours for Mrs. Ethel Torrey — 45. Also trimmed a large ash tree for Wm. Carter 2 hours — 50. Mrs. C. put up boards against the windows to prevent the great branches from breaking them. The branches were over the house. Early in eve. Mrs. Ethel Torrey sent two of her children here with some doughnuts and cookies for me. Also Mrs. Ella Sharpe sent her boy and a jar of pear preserves. Weather to-day cool. W.N.E. Played on the guitar 1hr 10 min in eve.

29th. (Sun.) Clear, cool. W.N.E. eve. cold. clear. 11 P.M., tem. 46. Have been getting ready to move from here — I do not know where I shall go.

The Treaty of Peace was signed yesterday at the Palace at Versailes [sic], Fr. […] Eng., Fr., Italy, Bel. and the United State of America (and other allies) and Ger., Servia [sic], Montenegro, Por. This closes the greatest war the world has ever known — over 17,000,000 lives lost dur. the war — men, women, and children K., starved, died of exposure. Only about 6,000,000 of them soldiers. I heard the guns on the warships in Boston Har. and vic. Firing salutes. U.S. has over 450,000 troops in Ger. now. 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th Div. of Regulars.

30th. Mowed with the sickle and shears — 6 1/2 hours for E. Jane Litchfield — 1.50. Had dinner there. Rode up to my home with […] Litchfield — Louis Litchfield’s son. Beechwood. Walked back to N. Scituate. Bought a qt. of milk at Mrs. Merritt’s. I also bought some

PAGE 335

bread at Fred Litchfield’s to cary to N. Scituate. Charles Bailey called here in eve. to get me to do some work for him. Emma and her children spent […] at place where I worked to-day. Fine weather. Clear. Cool. W. E. and S.E. Eve. very cool.

* * *

If you are interested in viewing the diary in person in our library or have other questions about the collection, please visit the library or contact a member of the library staff for further assistance.

*Please note that the diary transcription is a rough-and-ready version, not an authoritative transcript. Researchers wishing to use the diary in the course of their own work should verify the version found here with the manuscript original. The catalog record for the George Hyland’s diary may be found here. Hyland’s diary came to us as part of a collection of records related to Hingham, Massachusetts, the catalog record for this larger collection may be found here.