by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

A few years ago, I posted to the Beehive about Noah Worcester of the Massachusetts Peace Society and his objections to the way battles were commemorated. Worcester believed, in short, that we should celebrate peace, not war. He interested me because, although a Revolutionary War veteran himself, he took an unpopular but principled stand against the hyper-nationalism and bravado that he believed only served to further divide people from each other.

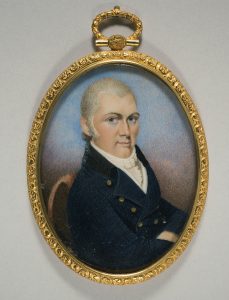

In the records of the Bunker Hill Monument Association, I recently came across another compelling letter by a Revolutionary War veteran who dissented from prevailing opinion. His name was Caleb Stark, and his language was so powerful I decided to investigate further.

If it’s possible to have military service in your blood, Caleb Stark had it. His father was Maj. Gen. John Stark, and his mother Molly worked as a nurse to the troops during a smallpox epidemic. Caleb was only 15 when he ran away in 1775 to join his father at the front lines, and he arrived on the eve of the Battle of Bunker Hill. He would serve through the rest of the war, eventually attaining the rank of major.

He was a natural choice for membership in the Bunker Hill Monument Association. The BHMA was founded in 1823, as the fiftieth anniversary of Bunker Hill was approaching, and its mission was to design, fund, and build a monument to those who had served in the battle. The association’s officers wrote to Stark to notify him of his election to membership. His answer, dated 10 April 1825, was possibly not what they were expecting.

I have powerful national objections to the adoption of this project, for the following reasons. First those who made this notable stand on this sanguinary hill, have almost all passed to those shades where military honors are not more highly appreciated than they have been in the United States.

In other words, the monument was too little too late. Most survivors of the battle had died in the intervening years. But Stark was just getting started.

Secondly, the actors in this bloody scene (the Revolutionary war) after having performed their part in a manner, perhaps unparalleled in antient or modern history, were refused by the government the rewards that were so solemnly promised in the hour of the most critical danger, & while the government has found ways & means to satisfy all other legal, & many illegal demands, they still continue a deaf ear to the crying demands for justice claimed by the disbanded officer & soldier. And now Sir in room of giving them the bread (that was solemnly promised), the debt is to be paid by a stone!!

I assumed Stark was referring to military pensions. In a biographical sketch written in 1860 by his son, Stark is described as an advocate on that issue, and his “testimony secured pensions to all whose cases he represented at the war department.”

Stark continued:

It is not to be denied that after a lapse of forty years 14,000 of the soldiers who were state paupers have been transfered to the United States, but the utmost care has been taken to preclude all others from the just claims due by the high national compact on the one side, & the discharged soldier on the other. These considerations have induced me to think that it would redound more to the honor of this rising powerful nation, to obliterate every vestige of the revolution, rather than have such a foul stain of ingratitude & injustice, coupled with the heroick deeds, privations, & suffering of the authors of the revolution.

Forceful words: better to forget the Revolution entirely than to neglect or mistreat its veterans and their families and then try to placate them with a monument.

What specifically were the “rewards” and “just claims” that Stark referred to? His son’s biography answers this question. It includes the text of a long article written by Stark and published in a local newspaper in 1835. Here is one of the relevant passages:

How have they [the United States] fulfilled their contract with the soldiers of the revolution? When it was necessary to continue the army in 1776, Congress, by a resolve of September 16, promised the soldier, in addition to his pay, one hundred acres of land in case they would join the officers and conquer the country. They closed with these terms, and by unparalleled suffering, exertions, and consummate bravery, in eight years cleared the country of its enemies, leaving the United States government in quiet possession of our immense public domain. Two years after the peace, May 20, 1785, resolves were passed for furnishing the soldiers the promised lands; but especial care was taken to saddle the law with a supplement, requiring the lands to be located in plats of six miles square, so that if two hundred and thirty soldiers could not be collected, and induced to combine in the location, they could not obtain their land.

The similarities between his language here and that of his letter to the BHMA indicate, I think, that this was Stark’s primary grievance. And he couldn’t hide his disgust at Congress’ self-dealing.

But Congress, farther to exhibit their love of justice and honor, enacted a law that the soldier might assign his right to the honorable fraternity of speculators, many of whom were members of the honorable Congress.

Stark goes into great detail about the maneuvers used to cheat veterans in favor of wealthy speculators, from reducing the size of land awarded to instituting a statute of limitations for claims. In fact, when he wrote the article, he had already spent nine years prosecuting his claim against the U.S. government for family land in Ohio. He ultimately won that fight, but learned in the process that “gratitude is a virtue often spoken of with apparent sincerity, but not so frequently exhibited in practice.”

In spite of his refusal to join the Bunker Hill Monument Association and his bitterness about promises broken, Stark did attend the ceremony for the laying of the monument’s cornerstone in Charlestown, Mass. on 17 June 1825. At 65, he was reportedly the youngest survivor of the battle of the 190 veterans in attendance. Noah Worcester of the Massachusetts Peace Society was not there.

I like to highlight the dissenting opinions of people like Stark and Worcester because they provide a fuller understanding of historical events that often come down to us simplified and sanitized. History is messy, and the closer you look, the more layers of compexity you find.

Select Bibliography

Bunker Hill Monument Association records, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Colby, Fred Myron. “Stark Place, Dunbarton.” The Granite Monthly, a New Hampshire Magazine, Devoted to History, Biography, Literature and State Progress, vol. 5, 1882, pp. 80-88.

Stark, Caleb. Memoir and Official Correspondence of Gen. John Stark, with Notices of Several Other Officers of the Revolution. Concord, N.H.: G. Parker Lyon, 1860. pp. 344-

Stearns, Ezra S., ed. Genealogical and Family History of the State of New Hampshire: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Founding of a Nation, vol. 1. New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1908. pp. 438-439.

Warren, George Washington. The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association During the First Century of the United States of America. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1877.