By Laura Williams, Visitor Services Coordinator

It was a sad day for treasure hunters across the U.S. when on 6 June 2020, millionaire art dealer Forrest Fenn’s legendary treasure was reported as found. Hidden in the Rocky Mountains for 10 years, the only clues to find the chest filled with gold coins and nuggets were a map and a poem. Like most mysteries, this treasure hunt did not come without a fair share of darkness as it is believed that 4 people died on the quest. [1] As I learned more about this present day treasure hunt, I could not help but think back on other tales of hidden riches that have puzzled treasure seekers and historians alike. From the pirate Blackbeard to the Aztec Emperor Montezuma II, legends of hidden treasures are as old as time. In fact, one such treasure that is still missing is the rumored bounty of the pirate ship the Whydah which sank just off the coast of Cape Cod, Mass..

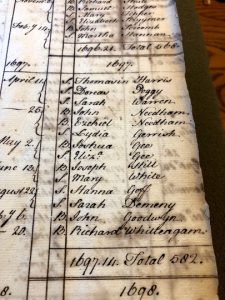

The Whydah had a dark past before it was captured by pirates, as it was originally a merchant slaver used within the Triangular Trade and the Middle Passage. It was boarded by pirates as it left Jamaica en route to London in late February/early March 1717. The pirate crew was led by Samuel Bellamy, or Black Bellamy, and the ship was soon loaded up with plunder as they made their way across the seas. In addition to weaponry and other valuables, the most intriguing facet aboard was the rumored 20,000 pounds of gold and silver. Captain Bellamy’s command of the ship was short lived, however, as it sank on 26 April 1717 after storm winds pushed it onto the shoals of Cape Cod. Only a handful of survivors were left and they were taken ashore to face trial in Boston.

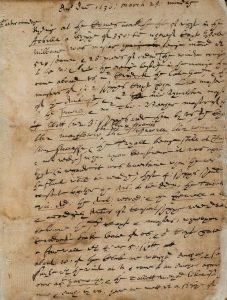

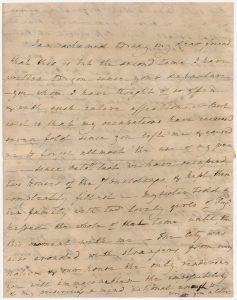

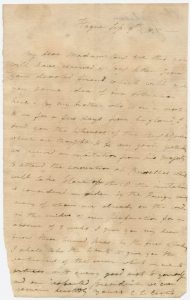

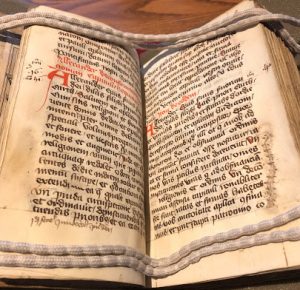

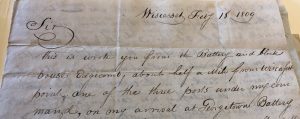

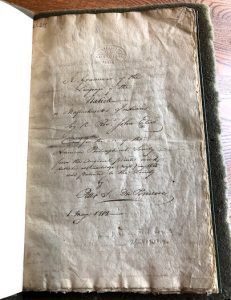

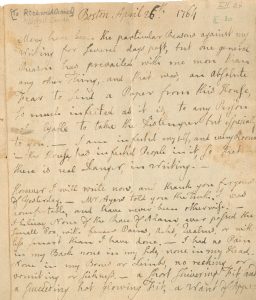

Immediately following the wreck, it is known that Cape Cod locals plundered the ship’s valuables. Cyprian Southack, a cartographer, was also hired to note the location of the shipwreck and gather treasures for the crown. More about his voyages and time serving the Mass Bay Colony can be found in the MHS’s Cyprian Southack letters collection. In fact, much of what we now know about the pirates comes from the priest Cotton Mather’s papers and his account of visits with the men in jail to provide them salvation. However, it was never confirmed whether or not the large bounty of treasure that the pirates gloated about truly existed.

Once six out of the seven surviving pirates were sentenced to death and executed in Boston, the Whydah remained buried under 30 feet of water for over 250 years. That is until 1984 when underwater explorer and Massachusetts native, Barry Clifford, found the ship’s remains and the Whydah became the first authenticated pirate ship wreck in North America. The thousands of artifacts discovered in the wreck can be seen at the Whydah Pirate Museum in Cape Cod, and Clifford has continued his search for the legendary treasure. In 2016, Clifford and his team stated that they discovered a large metallic mass off the coast of Wellfleet, MA that may contain most or all of the alleged 400,000 coins hidden below sea. [2] Further deconstruction of the mass will be needed to verify this claim.

As modern day treasure hunters continue their quests for riches, the journey will always begin with history and the clues that have been left behind. To learn more about the Whydah pirates, notorious Captain Kidd or Boston’s history as the “Port Where Pirates Hang,” take a look at our previous Beehive posts: The End of Piracy: Pirates hanged in Boston 300 years ago | Beehive & Piracy and Repentance | Beehive.

[1] Chappell, Bill. “Hidden Treasure Chest Filled With Gold And Gems Is Found In Rocky Mountains.” NPR.org, accessed on June 10, 2020. https://www.npr.org/2020/06/08/872186575/hidden-million-dollar-treasure-has-been-found-in-rocky-mountains-art-dealer-says

[2] Marcelo, Philip. “Explorer Barry Clifford claims he’s located famous pirate ship Whydah’s treasure.” patriotledger.com, accessed on June 19, 2020. https://www.patriotledger.com/news/20161007/explorer-barry-clifford-claims-hes-located-famous-pirate-ship-whydahs-treasure