by Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

This is the sixth part of a series about the letters to William and Caroline Eustis at the Massachusetts Historical Society. Click here to read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, and Part V.

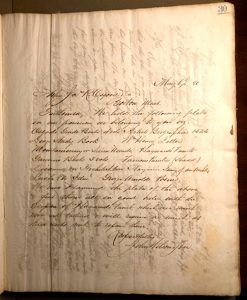

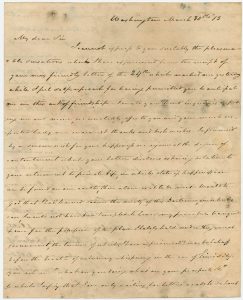

On 24 Sep. 1816, James Monroe wrote to William Eustis, U.S. minister to the Netherlands at the Hague, who had recently returned from a trip to Paris. Monroe’s letter contained this wistful passage about the city:

A view of that great metropolis, must be, at all times interesting, by the spectacle it exhibits, of the state of society, the sciences, & the arts; but from the disasters which have befallen it, in these latter years more especially, I fear that it has lost much of its charms. With many men in every party there, I was intimately acquainted. With some I was much connected in friendship; but some of these have disappeard, and others have experienced such changes, that there remain very few, to whom I could address a friend.

I was struck by the passage. Monroe was describing, in a personal way, the cataclysmic transformation of Paris wrought by the French Revolution and its aftermath.

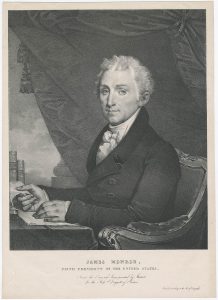

When he wrote this letter, Monroe was just a few weeks away from his election as the fifth president of the United States. The 58-year-old Virginian and Democratic-Republican had already had an illustrious career: he’d served as a senator, ambassador, governor, Secretary of State, and Secretary of War. Here, he was reminiscing to Eustis about his tenure as minister to France twenty years before.

Eighteenth-century Paris was the heart of the Age of Enlightenment. However, when George Washington appointed Monroe minister to France in 1794, the country was in the throes of the most violent phase of the French Revolution. Monroe arrived, in fact, just after the Reign of Terror and the execution of Maximilien Robespierre, which he heard about on his landing at Le Havre.

Monroe was “an ardent admirer of France and her Revolution,” explains historian Charles Hazen in his 1897 work Contemporary American Opinion of the French Revolution (p. 120). In his speeches and correspondence of the period, Monroe drew parallels between the French and American republics. Hazen describes Monroe as an “optimist” and “enthusiast” on the subject: “There is no passage in Monroe’s papers to show that he anticipated the breakdown of the Constitution, or the advent of a despot. […] He looked at everything with a strong republican bias, and his conviction that republicanism had come to stay in France seems to have remained unshaken” (p. 135-6). Monroe served as minister to France for two years.

In 1816, however, with the Bourbon Restoration in full swing and reactionary royalists and ultra-royalists returned from exile, Monroe was disillusioned. And his reference to friends that had “disappeard” takes on an ominous tone when we consider what happened to many of the revolutionaries.

He still had one friend in France, though, and that was the famous Marquis de Lafayette.

William and Caroline Eustis had visited Lafayette, and Monroe eagerly asked after him, his health, his circumstances, “who compose his family?” All three men were veterans of the American Revolution, and as Monroe said, “The friends of our revolution must always take an interest in [Lafayette’s] welfare, especially those who participated with him in that glorious struggle.”

The letter is long, running to four pages. Like much of the correspondence between public figures of the time, it covers a variety of subjects and alternates between official business and personal anecdote. Beginning with Monroe’s memories of Paris, the letter moves on to a detailed discussion of trade relations with the Netherlands, praise of Col. James Morrison of Kentucky, an inquiry into the weather, and news of the Monroe family.

James Monroe died on 4 July 1831. He was, coincidentally, the third U.S. president to die on Independence Day; John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both died exactly five years before.

To read Monroe’s letter and the rest of the letters to William and Caroline Eustis at the MHS, which have all been digitized, see the guide to the collection here. Our website also includes a number of other online resources we hope you’ll explore.

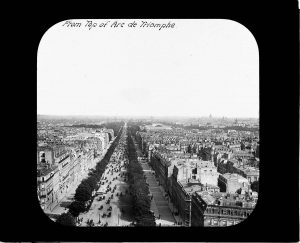

I’ll leave you with this photograph of Paris taken in the early 20th century from the top of the Arc de Triomphe.