By Susan Martin, Processing Archivist & EAD Coordinator

When you work with collections of family papers, there’s often one family member who, for whatever reason, stands out from the pack. This happened with me and Barbara Channing. Even before I knew anything about her, I couldn’t help liking her.

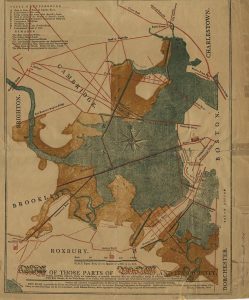

Barbara was born on 28 May 1883 in Brookline, Mass., the middle of the five children of noted psychiatrist Dr. Walter Channing. She had three brothers and one sister, but judging from the letters she wrote to her brother Henry Morse Channing, or “Hal,” she may have been especially close to him. You can find her letters in the MHS collection of Henry Morse Channing correspondence.

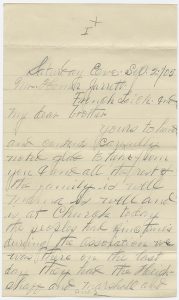

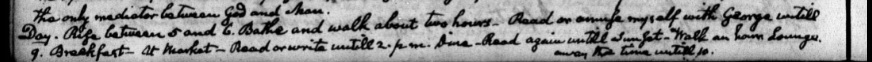

Hal was three years Barbara’s senior, and before he entered Harvard, his parents sent him to live and study in Germany for a year. Barbara wrote to him faithfully nearly every week, from August 1897 to August 1898. She was only 14 years old when he left and clearly idolized him.

I think it was her carefree, breezy writing style that first appealed to me. Her letters contrast with those of her father, who, in a loving but stern tone, frequently scolds Hal for the way he spends his money or manages his studies. Barbara’s letters are like a breath of fresh air.

For example, she describes spending her summer swimming, horseback riding, sailing, playing croquet, etc. She realizes how trivial these subjects must seem to Hal, so she excuses herself by saying, “A letter is a letter whether there is anything interesting in it or not.” Her letters are newsy, chatty, and gossipy, and when she runs out of material, she resorts to sending jokes or poems. Here is one of her original compositions:

There was a youth named Hal Channing,

Who after much fussing and planning,

Sailed across the blue sea,

To far away Germany,

And his brain now with German he’s cramming.

The MHS collection unfortunately doesn’t include Hal’s half of the correspondence, but it’s clear Barbara likes to get the same kind of letter from him. Once she tells him, “The kind of letter you wrote to me about all the funny things that happened to you and the funny things you saw I think is much more interesting and funny than a heap of discription [sic] about the scenery.”

Her slang is endearing. Things are bully, dandy, jolly, awfully this, or frightfully that. Modifiers are sometimes combined for emphasis (“It is perfectly terribly hot here to-day.”). Hal, all of 17 years old, is a “dear old man.” Instead of getting angry, people get “wrathy.” My personal favorite is Barbara’s description of her grandmother’s chocolate pies: “whackingly good”!

As cheerful and confident as she seems in her correspondence, Barbara is apparently shy and quiet in real life. She is frequently mortified in the presence of young men. One evening, she attends a dinner party thrown by her oldest brother Walter. She describes her nervousness in the company of the older girls (“I looked like such a little kid”) and her inability to make satisfactory conversation.

In spite of this shyness, Barbara has very close friendships. In almost every letter she mentions the Whitneys, neighbors who seem to be almost a second family for her. The Whitneys consist of father Henry Melville Whitney, mother Margaret (Green) Whitney, four daughters, and a son. The three oldest girls, Ruth, Elinor, and Laura, are around Barbara’s age.

Another of Barbara’s likeable qualities is her good-natured self-awareness. She acknowledges her own faults. These include difficulties at school, particularly with algebra and Latin; a tendency to bicker with her siblings; a certain nonchalance about church; and general naughtiness. But she is trying to improve herself: “I really am going to try not to lose my temper more than once a day. I may have to decide on twice a day.”

She also passes along local gossip, but she’s never unkind. In fact, here’s what she has to say about the engagement of Pauline Shaw to Laurence C. Fenno, which I think is pretty adorable:

Miss Pauline Shaw is just engaged. She is about thirty-five, and he forty. […] It is great fun to see them together in church, you know what I mean. Sort of hidden spoon. When they look at each other, there is a great deal of hidden spoon. They will make such a good couple. There both tall, he a little taller than she, and both very good looking. I’m sure you would like church better if you could see them. I watch them a lot. I suppose it is wicked but I do.

Barbara’s letters reveal an intelligent, lively, and above all very funny young woman. For example, on sending Hal a Christmas card, she quips: “You were always very fond [of] cards. Cheer up, you can give it to me next Christmas.” Here’s another humorous passage:

I do write such rotten letters, and such short ones compared to you. Your’s [sic] are always so nice and long, but really nothing ever happens exciting [here]. But last week Miss Bolles and Hayden got tipped out of the sleigh […] but they didn’t get hurt a single bit so that wasn’t so awfully exciting.

Barbara frequently teases Hal, knowing he’ll be embarrassed by her affection, but she’s also genuinely proud of him. She writes, “It is so nice to think of my big brother, good and fine enough to be able to have Mamma and Papa send him abroad alone.” She pleads with him to send her his picture, one of him looking her “square in the eyes.” He relents, and she keeps the picture on her dressing table.

All of this is not to say there are no dark clouds in Barbara’s life. In fact, the Channing family gets quite a scare in September 1897 when Barbara’s “severe attack of bowel trouble” turns out to be appendicitis and she requires an emergency appendectomy. The case is “unusually severe,” but she pulls through.

Dr. and Mrs. Channing, not wanting to worry Hal, don’t reveal the extent of the danger until after the fact, when Dr. Channing confesses to Hal, “Our anxiety and suffering to see Barbara so ill was quite beyond words, and even as I wrote you, the question of life and death was pending.” One of the few letters from Hal included in the collection is his reply:

I cannot tell you how much I have felt for dear Barbara, it has been such a terrible illness, and no on[e] except Barbara could have borne it as she has. She must have shown great patience and bravery, as I have heard that appendicitis is an exceedingly painful thing, and the slow convalescence must be very trying to one with a disposition as energetic as Barbara’s. It is terrible to think now what might have happened, and I so far away from home.

During Barbara’s recovery, Mrs. Channing writes, “She looks very well, and is just her old jolly happy self, joking often & enjoying all there is to be enjoyed.” Barbara, unable to sit up in bed, scribbles a little note at the bottom of her mother’s letter sending Hal “heaps of love.” Her sense of humor certainly survives intact. When Hal himself gets sick, she chides him, “You have not any business to behave that way. One sick in a family is plenty.”

Another significant event that weaves its way into the Channing family is the outbreak of the Spanish-American War. Hal is ashamed to be away and wants to return to the states and join the army. His father advises him to defer his decision, saying the matter isn’t as urgent as he believes and there are enough men for the war. In Barbara’s letters, we get a slightly different spin: “Papa won’t let Walter go and your [sic] younger, so I’m pretty sure he wouldn’t let you. He doesn’t know that you think you ought.”

The war, however, does preoccupy her. She writes about it several times, saying things like, “It seems so terrible to think of war. I suppose we don’t half imagine how bad it will be. […] I can’t really think what an awful thing war is.” And later:

It seems perfectly fearful to think about this war and somehow I simply can’t think it is justifiable. You won’t go into it. If they really needed you it would be different only it would be terrible to have you go away. I only hope that all will be settled soon, though things seem to be worse all the time. I won’t be mournful anymore.

Barbara Channing married Dr. Donald Gregg in 1912 and died on 28 Mar. 1960 at the age of 76. She is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass.

Henry Morse Channing returned to the states, attended Harvard, and became a lawyer. The MHS also holds a collection of the diaries he kept while he was studying in Europe between 1897 and 1898. He married Katherine Minot in 1904, and the couple named their oldest daughter Barbara, probably after his sister.

I’ll leave you with one of Barbara’s typical sign-offs:

I would like to say a lot of affectionate and nice things but I wont for I suppose you would think they were silly but if you don’t, know that it’s just the same as if I had written them down and you will always be the same very dear brother. Ba.