by Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

Dear Reader,

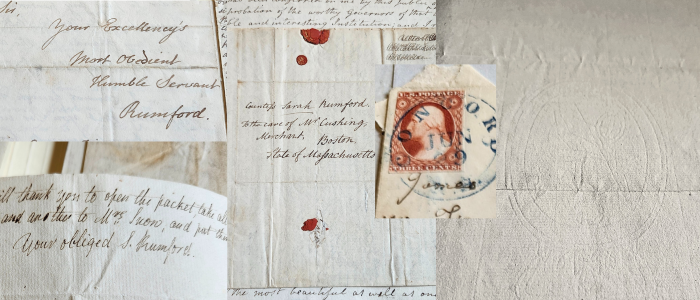

How did you enjoy the “rich mental feast” of Anne MacVicar Grant’s Letters from the Mountains? (Not ringing a bell? You have a bonus blog post to read!) I so enjoyed getting to know Mrs. Grant. It’s easy to fall in love with someone through their letters—what merits inclusion, what advice they give to one in need, how they comfort a friend who mourns, and especially the humorous and generous way they see those around them.

My only sadness in reading Grant’s Letters is the fact that she and Abigail Adams never met. We’ve all read a book or listened to a lyric that felt like it was written just for us. How badly do we want to sit down and chat with someone who understands us on that profound level? I have no doubt Adams and Grant would have been the best of friends.

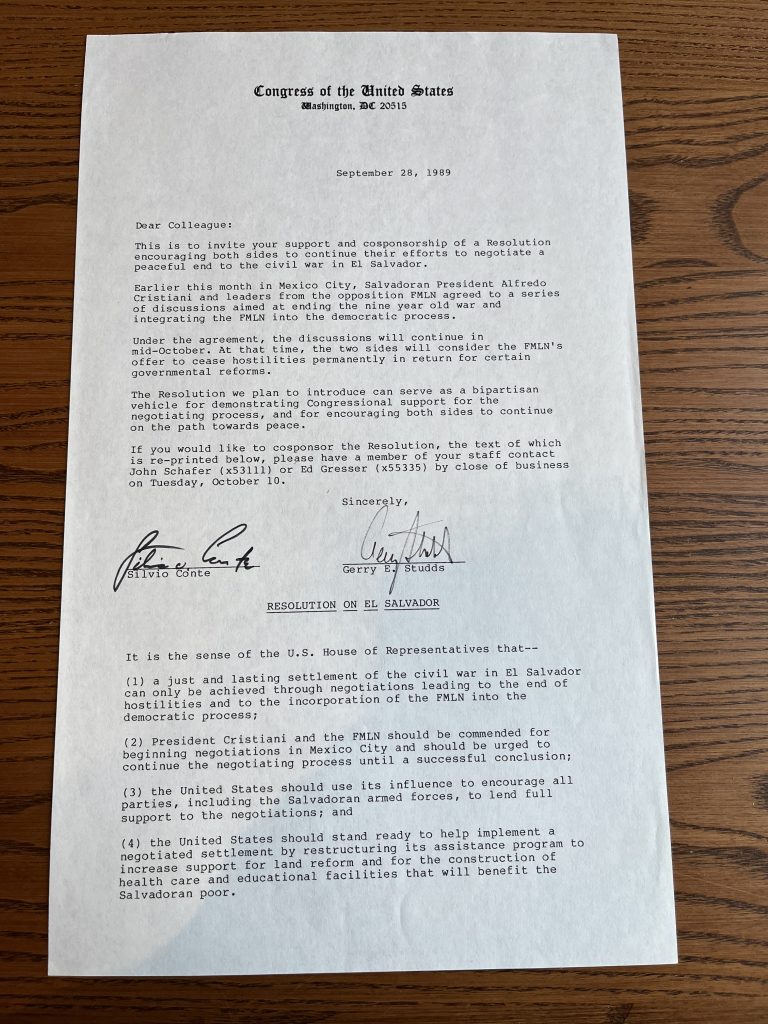

Speaking of Abigail’s dearest friend, last time I promised that John would have the next pick. While I desperately wanted to pick a fun book that I would enjoy reading, in my heart of hearts I know John’s idea of fun has to do with the science of government. Thus, our pick is William Ellis’s translation of Aristotle’s Treatise on Government.

Don’t click away yet! I can redeem myself!

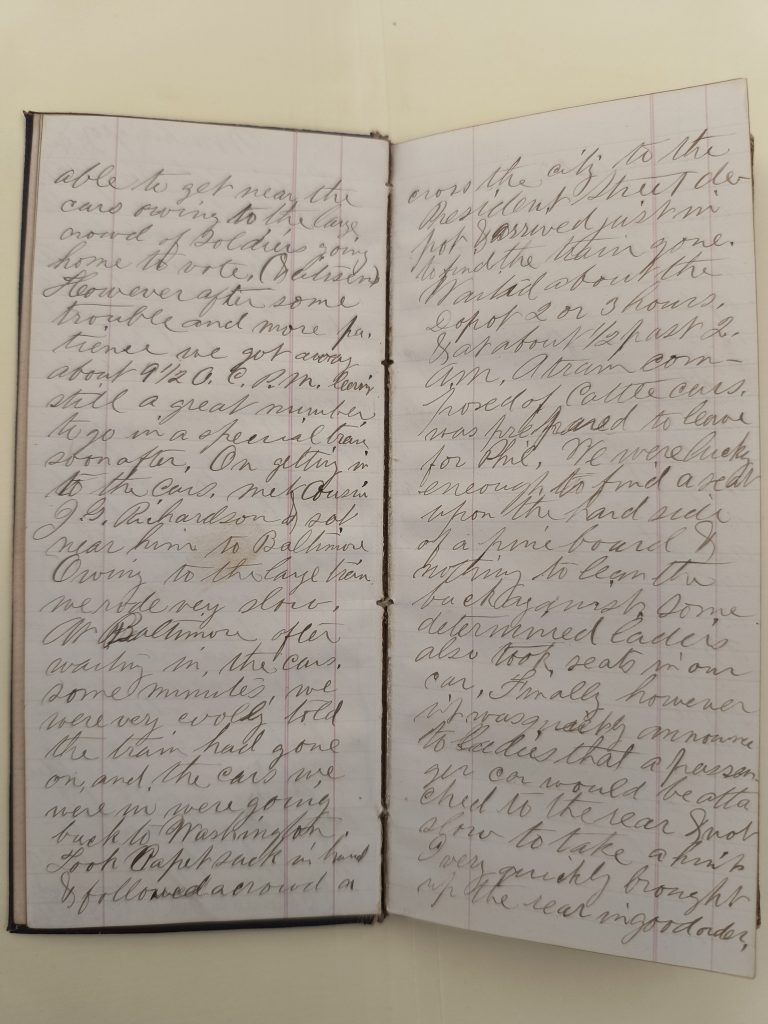

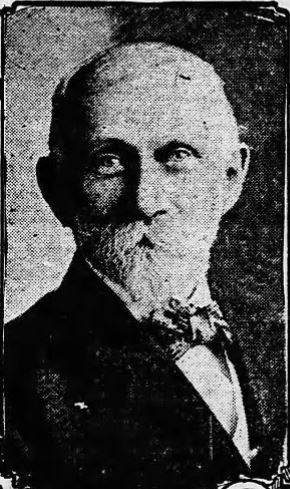

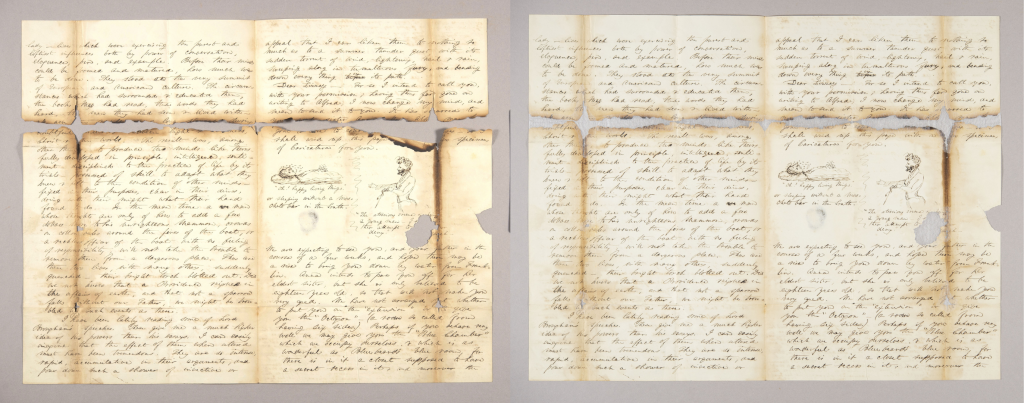

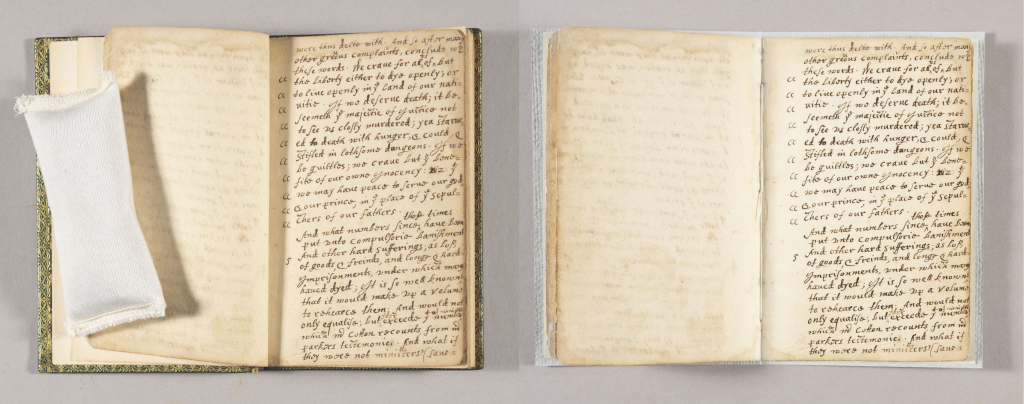

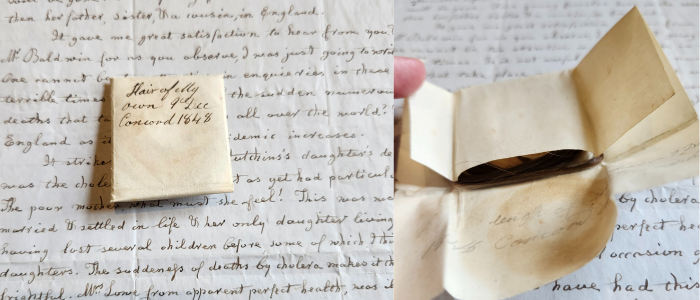

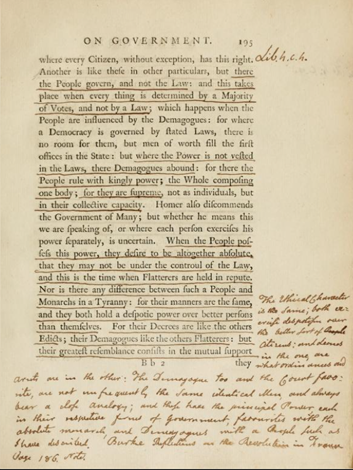

Our friends at the Boston Public Library hold John Adams’s actual copy of the book and have kindly digitized it for the public—marginalia and all!

What better way to get inside a person’s head than to see what sentences struck them and required underlining? Or to read where they disagreed and why? This is essentially a chance to pick John Adams’s brain. Seize it!

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute. Major funding for the John Quincy Adams Digital Diary was provided by the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund, with additional contributions by Harvard University Press and a number of private donors. The Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Historical Publications and Records Commission also supports the project through funding for the Society’s digital publishing collaborative, the Primary Source Cooperative.