By Kenna Hohmann, Adams Papers Intern

Diving into the vast collections of documents in the Adams Papers has been one of the best parts of my internship at the MHS. Over the past few months, I have endeavored to identify quotations and stories that allow for a greater understanding of and connection to the historical figures from our nation’s past. My research yielded both lighthearted moments—the Adamses’s comments on the seasons—and serious reflection—the family’s thoughts on education. A few had another theme in common— horses—a subject that because of person interest sparked my curiosity and prompted a deeper dive into the documents.

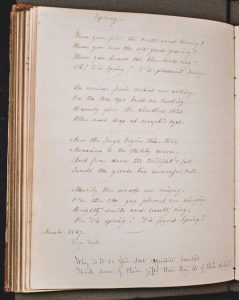

The first story I found reflects the hardship that sometimes goes along with riding long distances. In the spring of 1794 Thomas Boylston Adams (1772–1832), the youngest son of John and Abigail Adams, spent five weeks traveling through Pennsylvania. Thomas Boylston was 21-years old at the time and trying his best to establish his legal career, in part by taking “a journey into the interior parts of this State upon a Circuit with the Supreme Court.” Writing to his mother in June, Thomas Boylston provided a detailed description of the country he traveled t, commenting to Abigail “The exercise of riding on Horseback so long a Journey was rather more severe than I have been accustomed to, but tho’ it took away some of my flesh, it contributed much to my health.” Thomas Boylston experienced the physical pain caused by long periods of riding but also the benefits of the trip to his health and wellbeing. As someone who has also ridden horses over long distances, I can appreciate how the soreness of riding could be overlooked due to the joy that comes from being in nature. Thomas Boylston Adams was entering a new period of his life. That excitement, along with the beautiful Pennsylvania spring and a good horse and long ride, was enough to lift his spirits.

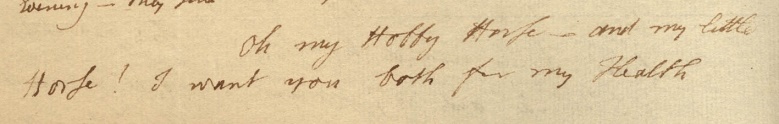

In a twist on the theme, the second story I found came from John Adams in a February 1795 letter to Abigail Adams. Then vice president, John Adams had been in Philadelphia since the previous November, while Abigail remained in Quincy. John, along with most Americans, was eagerly awaiting the arrival of the Jay Treaty from Britain, although the vice president also feared the treaty might delay his return home. “Oh my Hobby Horse—and my little Horse! I want you both for my Health And Oh my I want you much more, for the delight of my heart and the cheering of my spirits—” John frequently referred to his farm as his “Hobby Horse” and when he wanted a break from the stress of politics he turned his thoughts toward home to lift his spirits. In this selection, his love for Abigail Adams and her importance to him is on full display.

My personal interest in horses and subsequent search for related content yielded these two different but interesting anecdotes. The sweet words between John and Abigail Adams and the humorous yet earnest letter that Thomas Boylston Adams sent to his mother would not have come to my attention without my original interest in the theme of horses. Spending time with the expansive collection of the Adams Papers has been a highlight of my internship, and I would recommend that everyone take a bit of time to read a few letters! To get started, visit the Adams Papers Digital Edition.