By Gwen Fries, Adams Papers

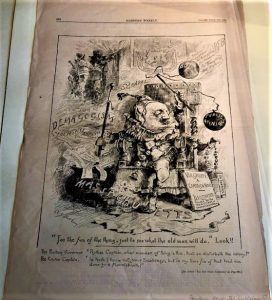

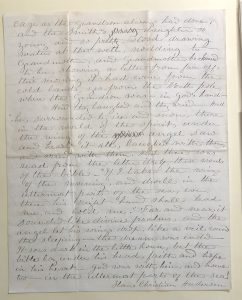

It was an open secret that the Adamses were no fans of Alexander Hamilton. Senator John Quincy Adams couldn’t even be prevailed upon to wear crape, join in a funeral procession, or “join in any outward demonstration of regret” after Hamilton’s untimely death. When chastised by his wife, JQA responded that he “had no respect” for the fallen statesman.

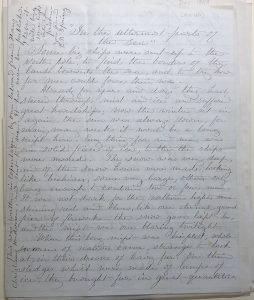

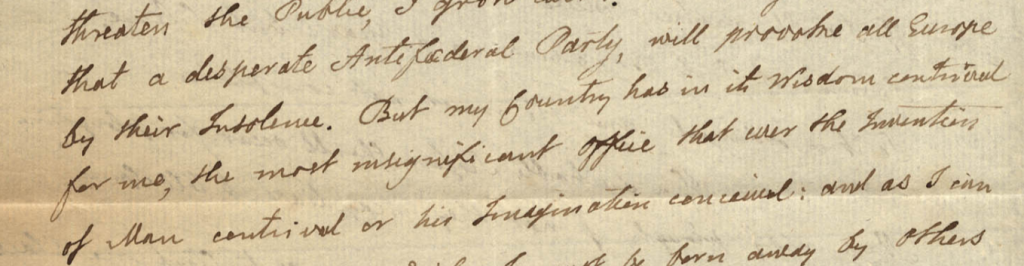

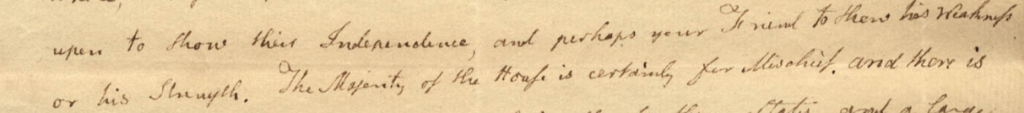

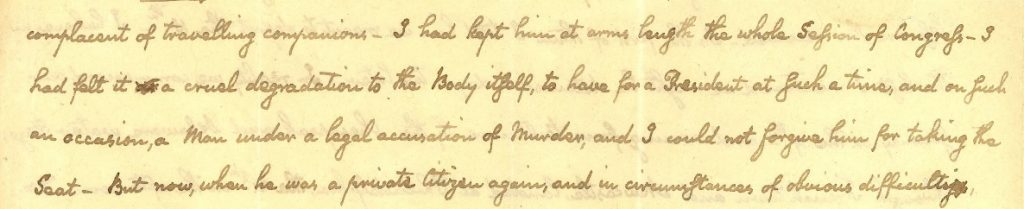

Nor did he much respect the man who had stood opposite Hamilton in the early hours of 11 July 1804, and his respect for Burr only plummeted further when Burr dared to return to his station as President of the Senate. Adams admitted he had kept Burr “at arms length the whole Session of Congress,” feeling it “a cruel degradation to the Body itself, to have for a President at such a time, and on such an occasion, a Man under a legal accusation of Murder.” Adams “could not forgive him for taking the Seat.”

When the second session of the Eighth Congress came to a close on 3 March 1805, Burr gave a farewell address—“the last act of his political life,” as Adams thought—and John Quincy left the Senate Chamber for home, convinced he had seen the last of Burr.

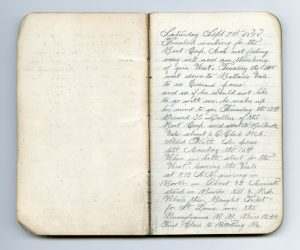

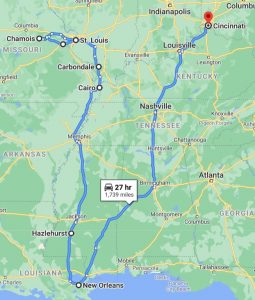

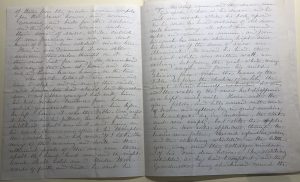

On 19 March, John Quincy and Louisa Catherine boarded a ship in Baltimore, sweating in the unseasonably warm weather, two sick and fitful toddlers in their arms, ready to get the trip over with and reach their next destination of Philadelphia. (When they later arrived in Philadelphia, the Adamses’ old friend Dr. Benjamin Rush diagnosed the boys with chicken pox and whooping cough.) An overwhelmed Louisa Catherine recorded in her diary that “the Children were both quite unwell and of course very troublesome It was the first time that I had the entire charge of them.”

One can imagine the sinking of already low spirits when the Adamses got on board and were greeted by Aaron Burr. Having been much affected by Hamilton’s demise, Louisa confided to her diary that she “felt a sort of loathing for this Col Burr.”

Within a few hours, Louisa—and everyone else on board—had fallen under his spell. “He appeared to fascinate every one in the Boat down to the lowest Sailor and knew every bodies history by the time we left— He was politely attentive to me . . . At Table he assisted me to help the Children with so much ease and good nature that I was perfectly confounded.”

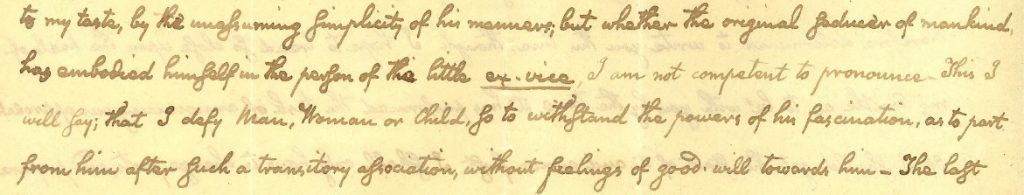

When relaying the event to his brother, John Quincy wrote, “Whether the original seducer of mankind, has embodied himself in the person of the little ex-vice, I am not competent to pronounce— This I will say; that I defy Man, Woman or Child, so to withstand the powers of his fascination, as to part from him after such a transitory association, without feelings of good-will towards him.”

After a particularly rough passage—so rough, in fact, that at one point Louisa rolled out of her high berth and onto the floor—the Pennsylvania soil was a sweet sight to the passengers. Taking pity on the sleep-deprived parents of fussy young children, Burr swooped in, taking little John Adams II in one arm, taking Louisa’s luggage in the other hand, and offering her his arm to disembark. John Quincy followed behind them, George Washington Adams in his arms, his jaw on the gangplank.

“It was all done with so little parade and with such entire good breeding that it made you forget that he was doing any thing out of the way,” Louisa recalled. “He talked and laughed all the way and we were quite intimate by the time we got to Philadelphia where he called to see us, and this the first and last occasion on which I ever saw this celebrated man.”

After two weeks’ rumination, John Quincy summed up the experience by writing, “I had not strength of mind enough to retain in their full inflexibility the resentments even of Virtue— I felt a degree of compassion for the Man, which was almost ready to turn to Respect— He was more than barely civil to me and my family— I could not help feeling for him in return more kindness, than I was willing to acknowledge to myself—infinitely more than I suffered myself to shew him; and perhaps more than is justly consistent with that character which on a cool and distant estimate I cannot help believing to be his.”

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the Packard Humanities Institute, and the Amelia Peabody Charitable Fund. All Adams Papers volumes are published by Harvard University Press.