By Heather Rockwood, Communications Associate

In Part One of this story, we discussed John Quincy Adam’s (JQA) diary entry from 1 December 1786, in which he described an altercation along a snowy riverbank between militiamen and a leader of the Regulators, a force of men formed to fight back against the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as a result of heavy taxes on the financially burdened citizens of Western Massachusetts.

Going back several days in the diary to 23 November 1786, JQA writes about the “insurgents” coming to Cambridge where he is attending Harvard:

Whitney arrived in the evening; he comes from Petersham, in Worcester county, and says the insurgents threaten coming to prevent the setting of the court of common pleas, in this Town, next week.

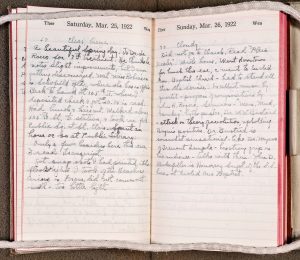

On 27 November 1786, he writes in a more excited manner:

This evening, just before prayers about 40 horsemen, arrived here under the command of Judge Prescott of Groton, in order to protect the court to-morrow, from the rioters. We hear of nothing, but Shays and Shattuck: two of the most despicable characters in the community, now make themselves of great consequence. There has been in the course of the day fifty different reports flying about, and not a true one among them.

In the days that followed, it is clear this excitement is not JQA’s alone. On 29 January 1786, he reports that:

Lovell, a classmate of mine, is half crazy, at hearing so much news. He wants to be doing something, and is determined by some means or other to fight the insurgents. He says he is no politician, he was made for an active life, but he cannot live in a place, where there is so much news.

It is also clear that JQA has no inclination to join the militia, only the urge to record the news in his diary, which he writes with as much enthusiasm as the dinners, dances, classes, and meetings he’s attending.

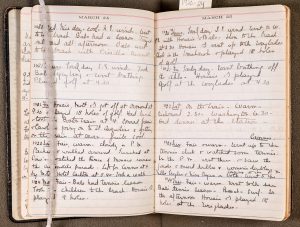

The sentiment towards the insurgents is not positive in Cambridge and elsewhere, as is noted in the original diary entry: “The gentlemen, were not molested however in bringing him off; but had every where every assistance given them, that they were in want of, and the apparent good will of every one, wherever they went,” as well as in his classmates wanting to fight the insurgents. On 30 November 1786, JQA reports that two militias moved through the area to try to chase down the insurgents who had turned around when they learned of the militia in Cambridge, and he records his own sentiments on the news:

There seems to be a small spark of patriotism, still extant; it is to be hoped, that it will be fanned, and kindled by danger, but not smothered by sedition.

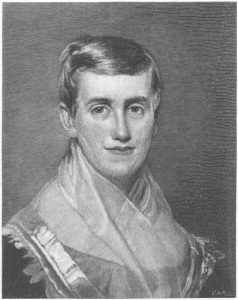

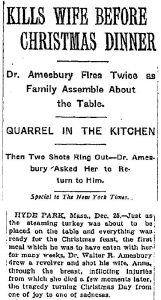

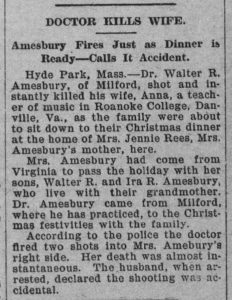

Job Shattuck, the man who was captured in the diary entry, had an interesting past and had been against the burdensome taxes since 1782. Twice he had been a war hero, first as a soldier in the Seven Years’ War, and then during the Revolutionary War. He was a farmer with a large house and more land than anyone else in Groton. His family, including his wife Sarah who detained a Tory courier during the Revolutionary War, were champions of liberty and wholeheartedly stood behind the Sons of Liberty. Shattuck felt that the taxes were excessive and the same as the taxes imposed without representation by Britain’s parliament. At fifty years old, his age, war experience, and local respect made him a natural leader. He and his Regulators successfully shut down the Concord court in September 1786.

In November 1786, Governor Bowdoin issued a warrant for Shattuck’s arrest, which brings us back again to JQA’s diary and its tale of Shattuck’s capture. During the altercation, his knee was wounded by a sword, and once brought to jail his injury was not tended to for four days. He was held for five months before his petition to be released was granted, but only on account of his still festering wound and his persistent community support. He returned home to Groton. It may be that the rebellion’s last effort in January 1787—when Shattuck was in jail—made Governor Bowdoin more willing to grant clemency.

Shattuck was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to hang, but a pardon from the governor could save his life. Fortunately for Shattuck, John Hancock was reelected governor and postponed the hanging. By July, Shattuck was pardoned. He walked the rest of his life with a crutch and died in 1819 at the age of 83.

However, the rebellion’s story ended much sooner for JQA. By 2 December 1786, he wrote:

The Court adjourned from hence this afternoon, and Cambridge is not at present in danger of being the immediate scene of action. These rebels have for these three months, been the only topic of conversation all over the Commonwealth.

Other resources for further reading on Shays’ Rebellion

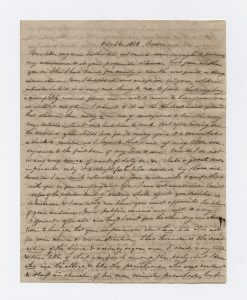

Petition from Job Shattucks, Middlesex County Court

Grand Jury Notes, October 1786

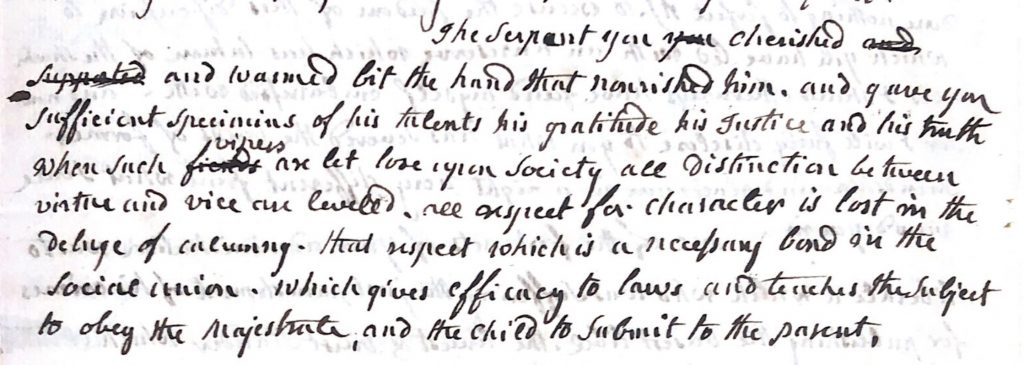

Letter from Mary Smith Cranch to Abigail Adams

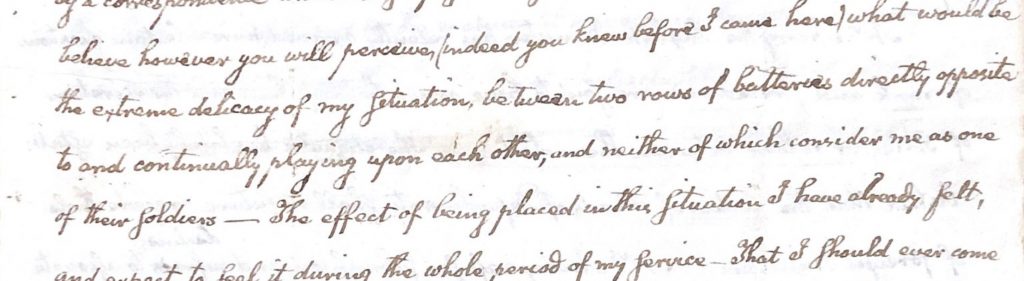

Letter from Benjamin Hichborn to John Adams