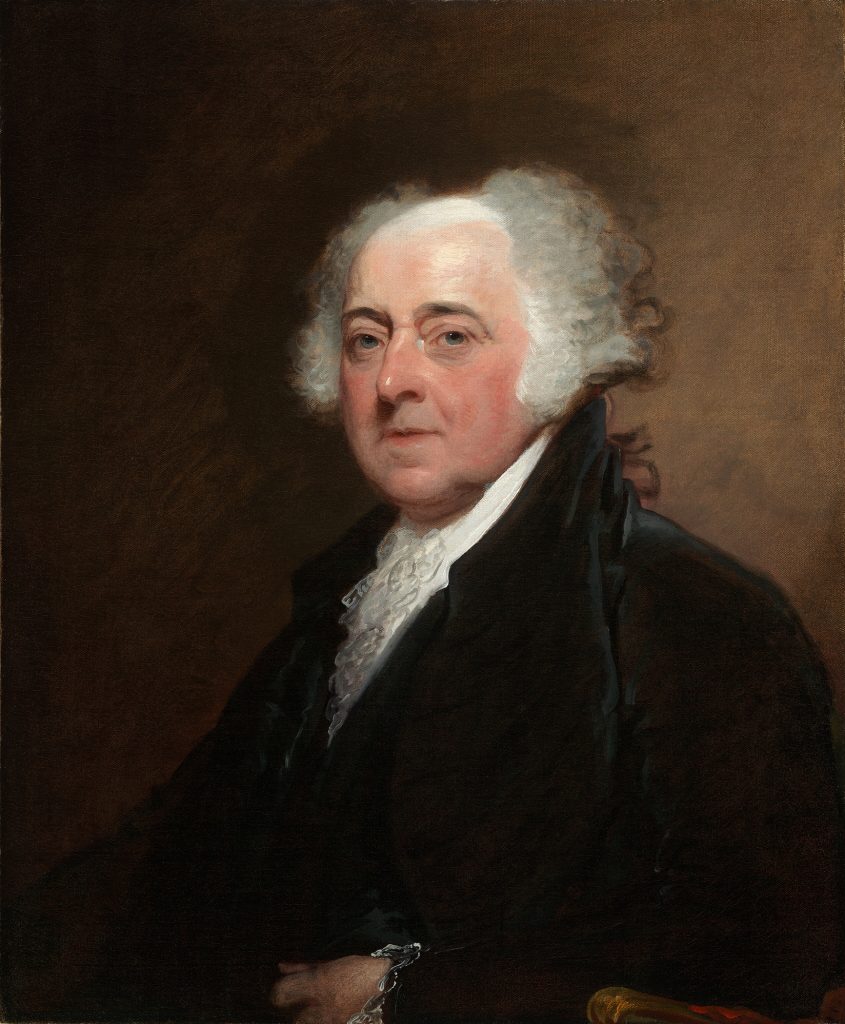

By Sara Georgini, Series Editor, The Papers of John Adams

John Adams and the United States government face a world afire with rebellion in Volume 21 of The Papers of John Adams, which chronicles the period from March 1791 to January 1797. With the federal system newly in place, fresh challenges crept in on all sides. Adams and his colleagues struggled to bolster the nation against a seething partisan press, violent clashes with Native peoples on the western frontiers, a brutal yellow fever epidemic in the federal seat of Philadelphia, and the political effects of the Whiskey Rebellion. “I Suffer inexpressible Pains, from the bloody feats of War and Still more from those of Party Passions,” he wrote.

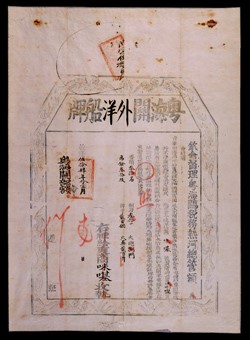

Working with President George Washington and an increasingly fractious cabinet, Adams dealt with the issues that defined U.S. foreign policy for decades to come, including the negotiation, ratification, and implementation of the controversial Jay Treaty, as well as the unsettled state of relations with revolutionary France. To the former diplomat, Europe’s abrupt descent into chaos signaled a need to uphold U.S. neutrality at any cost. “We are surrounded here with Clouds and invelloped in thick darkness: dangers and difficulties press Us on every Side. I hope We shall not do what We ought not to do: nor leave undone what ought to be done,” Adams wrote.

As most of Europe went to war, U.S. lawmakers tried to keep the nation afloat in the face of financial panic and frontier uprisings. Exploring the remainder of John Adams’ vice presidency, the 379 documents printed in Volume 21 portray a veteran public servant readying to fill the nation’s highest office. Though he wearied of the incessant politicking that came with building a government, Adams was committed to seeing his service through. “The Comforts of genuine Republicanism are everlasting Labour and fatigue,” he advised a friend in Switzerland.

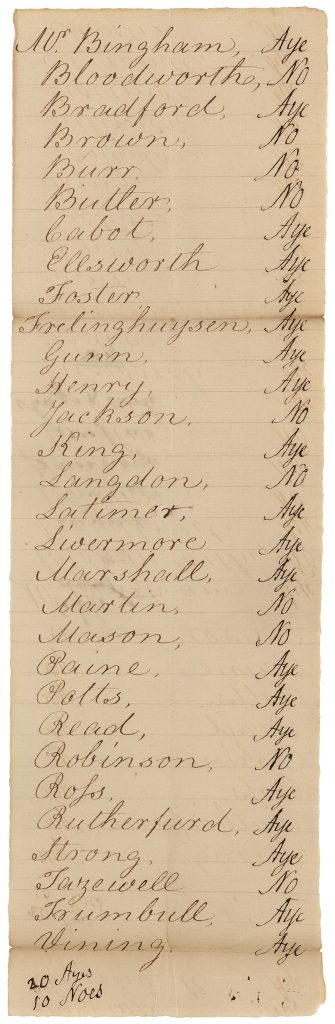

Several big stories unfold in the second half of Volume 21. On the high seas, persistent French attacks on U.S. trade punctured the new nation’s economic hopes and shredded Franco-American relations. An unpopular new deal with Great Britain, known as the Jay Treaty, roused popular discontent. Amid all this political uproar, John Adams squared off with Thomas Jefferson and others in the presidential election of 1796. Though modern campaigning was not yet in mode, grassroots electioneering seized center stage. Partisans for both the Federalist Adams and the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson skirmished in pamphlet wars and battled in the press.

John Adams prevailed, though he did not open and count the votes of his victory until 8 February 1797. In the interim, Adams planned his first steps in office. The job had changed since 1789. He was no Washington, and John Adams’ United States looked vastly different than it had even five years earlier. Anticipating his new role, Adams turned to Harvard classmate Francis Gardner with a blend of excitement and nostalgia. “The Prospect before me, of which you Speak in terms of so much kindness and Friendship, is indeed Sufficient to excite very Serious Reflections. My Life, from the time I parted from you at Colledge has been a Series of Labour and Danger and the short Remainder of it, may as well be worn as rust. My Dependence is on the Understanding and Integrity of my fellow Citizens, for Support with submission to that benign Providence which has always protected this Country, and me, among the rest, in its service,” he wrote. We are hard at work on telling John Adams’ story of presidential service anew in Volume 23.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding for The Papers of John Adams is provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.