By Heather Rockwood, Communications Associate

I love when different aspects of history intervene with each other. As my specialty is art history, I’m especially curious when developments or movements in art affect the ones preceding them—as seems to have happened when photography’s advent and popularity coincided with the waning of silhouettes as a popular form of portraiture.

Silhouettes came into fashion in the 18th century. Those skilled in the art form would travel around making silhouettes mostly for people who could not afford painted portraits. They were popular regardless of income and many wealthier people would commission silhouettes. A silhouette—a “shade” or “profile”—could be made in any media: painted, drawn, sewn, or cut from paper, this last method the most popular. The sitter’s image could be made freehand with scissors cutting paper, or by using light to trace a shadow. The cut out paper shape would then be pasted onto contrasting paper to make it stand out. What made this type of portraiture so popular was its convenience—almost anyone could do it in a few minutes—and at low cost. However, the same could be said of photography, even early photography. Although there was an initial set up cost to purchase or make a camera, the chemicals to develop the images were inexpensive and widely available. A photographer could take many portraits in a day. Photography, though, also had the irresistible advantage of capturing a person’s true likeness.

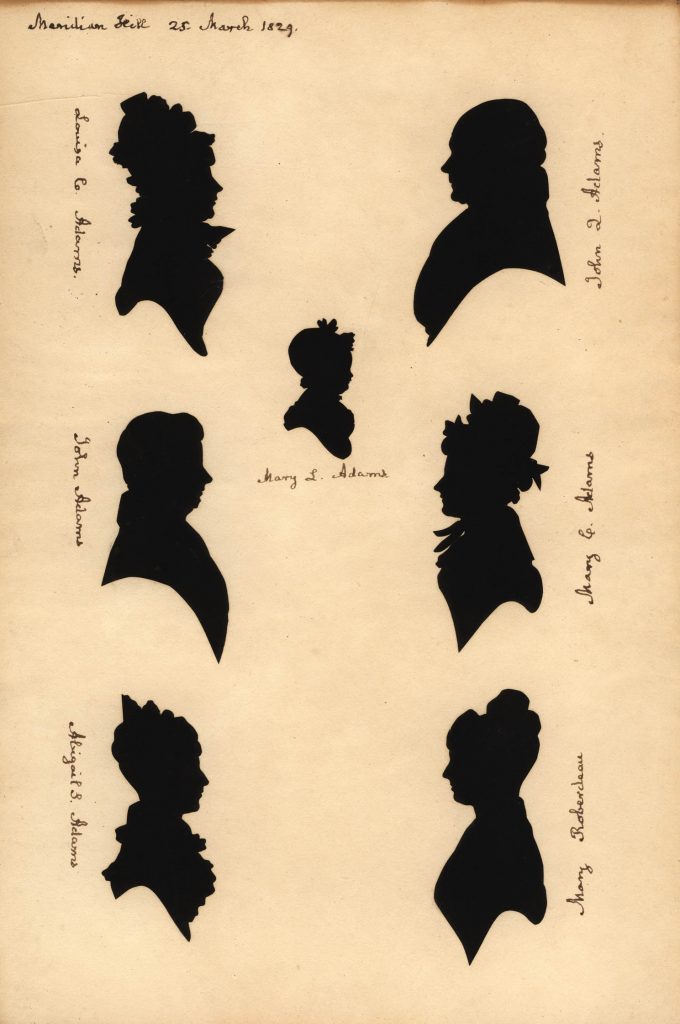

The MHS has a great collection of silhouettes, a few of my favorites shown below. I’ll start with the Adams Family which features silhouettes from 1829 of Louisa Catherine Adams (1775–1852), John Quincy Adams (1767–1848), John Adams (1803–1834), Mary Louisa Adams (1828–1859), Mary Catherine Hellen Adams (1806–1870), Abigail Smith Adams (1744–1818), and Mary Roberdeau (1774-?).

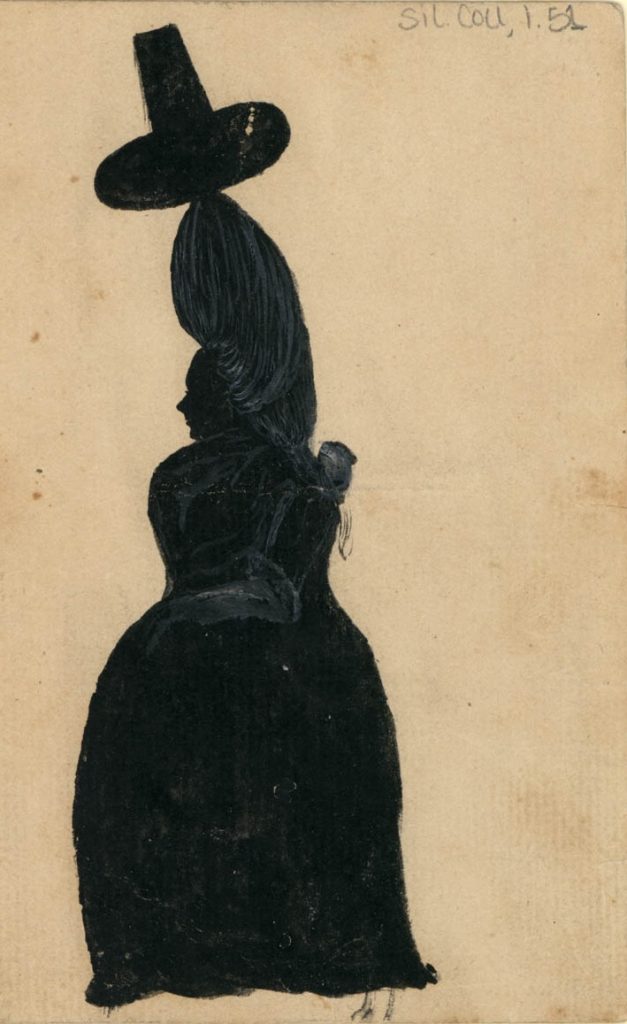

I also find this silhouette of Mrs. John Chadwick and two daughters endearing as the figures are full-bodied, showing off their fashionable clothes. It’s also touching that Mrs. Chadwick and her daughters appear to be holding hands. Another thing I love about this silhouette is that its creator lightly embellished the black cutout with a whitewash to highlight some of the details. You can see those details when you enlarge the online image here.

And the last silhouette I’ll share is part of the ongoing exhibition, Our Favorite Things—a silhouette of Lucy Flucker Knox from 1790. Of course, the towering hairdo and gravity-defying hat make this image stand out from the other more traditional silhouettes in the MHS collection, which is why I want to share it.

To see more silhouettes in the MHS collection see this search here.

![Comical drawing of a man with mustache and receding hairline, whose breeches extend up to his neckline. He holds a top hat in his left hand, a riding crop[?] in his left. Not signed.](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Freds-breeches-225x300.jpg)