By Miriam Liebman, Adams Papers

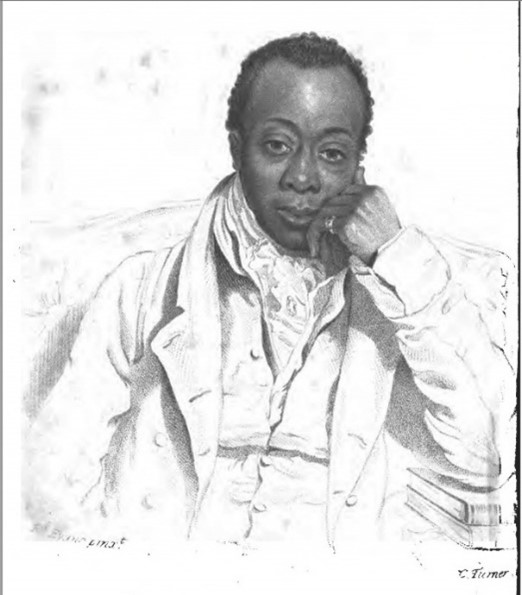

On the morning of 21 February 1811, John Quincy Adams, Louisa Catherine Adams, and other members of the diplomatic corps in St. Petersburg attended the public examination for the young women at the Institute of the Order of St. Catherine, which was located on the Fontanka River in St. Petersburg. John Quincy recounted this event a few days later in a letter to his mother Abigail Adams on 26 February. He explained that there were four classes of students, who began their education between the ages of six and ten years old and upon completing their education, they took a public examination, which occurred over the course of two days in February every other year. For the exam, the students “dressed alike, in a plain white muslin gown, with a scarlet ribband round the waist. Those who had distinguished themselves by peculiar merit wore nosegays of lilies of the valley at the breast.—They were all extremely graceful—Some of them had fine forms; but there was scarcely a beautiful face in the whole number.”

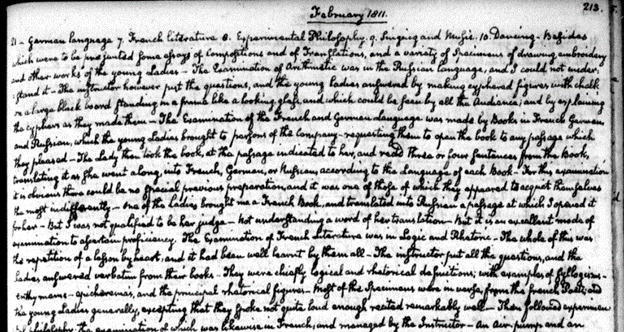

The school was under the patronage of the Empress Mother Maria Feodorovna, who invited the members of the diplomatic corps to attend. JQA noted in his Diary that the royal family, however, was not present at the event. The first day of the examination consisted of many subjects, including religion, philosophy, geography, history, and Russian history. The second day of the exam, which the Adamses attended, covered math, German, French literature, experimental philosophy, and the arts, including music, singing, and dancing.

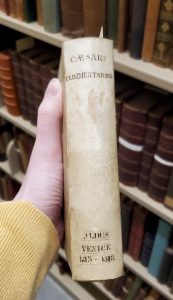

The foreign ministers who attended did not just watch the examination but participated in it as examiners. While John Quincy did not understand the arithmetic portion of the exam since it was conducted in Russian, when it came time for French language, “One of the Ladies brought me a French Book, and translated into Russian a passage at which I opened it for her—I presume she performed it well, but if she was qualified for her task, I was not so for mine…I saw that she read French with perfect ease, but the language into which she rendered it might have been Sanscrit or Chinese for aught I knew.” He was more “at home” for the portion of the exam on French literature and found the experimental philosophy portion to be “at least amusing.” This was followed by an exhibition of the young ladies’ art, including drawings and embroideries, and concluded with the portions on singing and dancing.

Despite the long examination, John Quincy believed that not many of the students were “so learned, or even so accomplished, as these exhibitions would seem to import.” He also lamented about how many of the subjects were not adequately taught to young men. He concluded, “Yet with every allowance which ought to be made for the varnish of a public exhibition, I know not how it would be possible to make more judicious or more excellent provisions for the Education of young Ladies of rank and fortune in this Country than we find here exemplified.”

Louisa offered a perspective of her own. She later noted in her diary, “None of them are handsome…The performance of their Religious duties is strictly attended to and their long fasts reduce them so much that they look like Skeletons– Of course their complexions suffer.” Louisa’s more sympathetic perspective may have been influenced by her experiences boarding in a convent in Nantes during the American Revolution when she was four years old and then a boarding school in London after the war ended. While she did not enjoy her time at the boarding school in London, she had a passion for reading. She described in her memoir, Record of a Life that she was not privileged to learn many subjects because “Many of the modern studies not then being thought requisite in the education of Women and being thought to have a tendency to render them Masculine.” While her education was mostly limited to arts and a rudimentary education in reading and writing, she did have the privilege to be tutored by a woman, Miss Young, who was trained in classical education. Louisa reflected quite positively on this moment of her education and viewed Miss Young with the highest respect and was grateful for the opportunity to learn and converse on such “masculine” topics. The value Louisa placed on education remained with her throughout her life and was something she and John Quincy prioritized as parents.