By Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

This is the eighth installment in a series. Click here to read Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part V, Part VI, and Part VII.

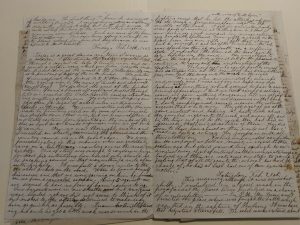

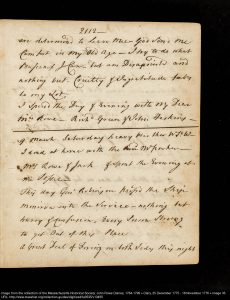

Thanks to those of you who’ve been following the story of Pvt. Howard J. Ford of the 43rd Massachusetts Infantry Regiment here at the Beehive. I’ve enjoyed doing this deep dive into his Civil War experiences, as told in his own words.

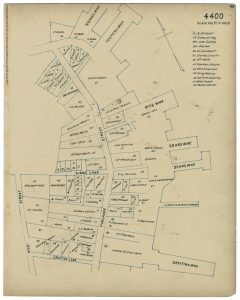

The weeks following my previous post consisted of alternating periods of dull routine and bustling activity. Howard’s company was stationed at New Bern, N.C., and was involved in various patrols, marches, and skirmishes in the area, including the successful defense of New Bern on the one-year anniversary of its capture by the Union and a fight at Blounts Creek. After the latter, Howard confessed that he was so tired, “If I was 50 last night, I was 70 years old tonight.”

There are a few general themes that recur in Howard’s journal during this time.

Moments of Quiet

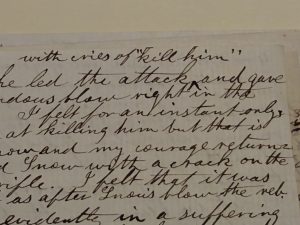

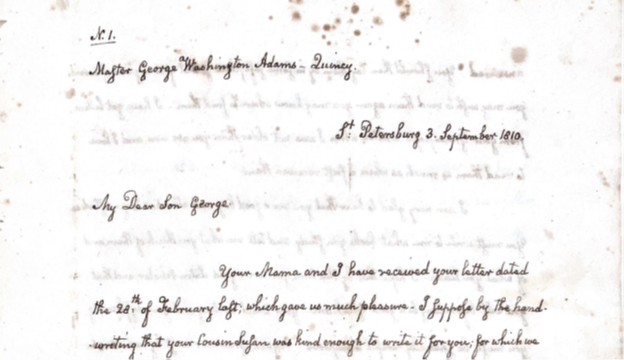

I’ve often felt the most moving passages in soldiers’ reminiscences are those moments of peace and quiet juxtaposed against the violence. For example, the day after Howard killed a Confederate soldier, he wrote, “I saw one little violet in bloom on the battlefield. It was the first wild one I have seen and I will send it home.” He also described standing so still on picket duty at dawn that birds approached within a few feet of him. Of course, nothing made a soldier more wistful than letters from home; Howard missed his “good wife,” “darling boy” (3 years), and “little daughter” (7 months).

The Troops’ Resourcefulness

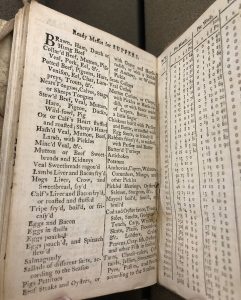

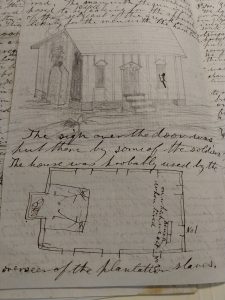

Howard attended a party in camp featuring music, recitations, and even ventriloquism. He was “astonished” by one musician in particular, who had crafted a violin from a hard tack box! “As to the workmanship,” he said, “no one would have suspected its humble origin. The glue even was made in camp.” According to Edward Rogers’ history of the regiment, “a camp of Yankees is a jack-knife paradise” (p. 128). Many of the soldiers were skilled artisans, after all. As I discussed in a previous post, Howard and friends built their own barracks from the ground up. Howard also made a ring for his wife out of a piece of bone.

Civilians and Soldiers

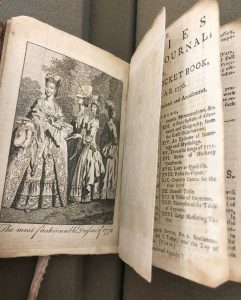

Civilian visits to camp, like one in March 1863 by the proprietor of the Boston Journal, were pleasant interludes, but also jarring ones. Howard wrote that, “A person in citizen’s dress looks as odd to us, as a monkey does to the children, when it is dressed up in a skirt and cap.” Edward Rogers agreed: “Amid warlike scenes,” civilians looked, well, ridiculous. “We were at home: they were not. Our individuality had been merged in each other until every man felt, in some respects, as though he had the strength of a thousand” (p. 135).

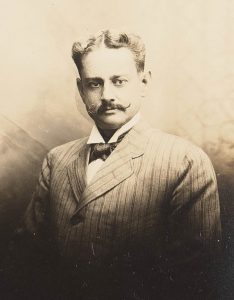

Cpl. James K. Odell

Howard’s admiration for James Kelley Odell is clear. Odell, a corporal in Howard’s company, was one of a large family originally from New Hampshire. He’d lost both of his parents by the time he was 21, as well as an older brother who’d accidentally shot himself as a teenager. Now Odell was 29 and had a wife and child back home. Here’s what Howard had to say about him: “I well know that he would stick by me if I met with harm, no matter what the consequences were.” On a grueling 15-mile march, in spite of weak lungs, “Odell stood it like a hero.” James K. Odell died in 1918 at the age of 84.

Tricks of the Trade

I enjoyed reading about the tactics used by soldiers to outwit the enemy. One night on picket duty, Howard, waiting silently in the dark by the side of the road, was more amused than scared when he heard curiously similar cow bells ringing from opposite sides of the road, as well as suspiciously human-like roosters. (“Perhaps the reason he did not crow any better was that he was somewhat sleepy.”) Howard also introduced me to “Quaker cannons,” logs mounted on cart wheels and painted like cannons to intimidate the enemy. Both the Union and the Confederacy used them.

I hope you’ll join me for the next installment!