by Cornelia H. Dayton, University of Connecticut

Stenographers were not present in the early courtrooms of settler New England. To gain insight into how a particular civil suit or criminal case proceeded, the researcher can examine, first, the folio-sized Record or Minute Book. This typically offers a short paragraph summarizing the case, which was written by the court clerk at the case’s conclusion. Second, the file papers, folded into a bundle, may survive. Minimally, one finds the original writ or indictment and often the bill of costs. If one is lucky, some witness depositions are wrapped in the bundle. However, these two forms of records for any given case do not constitute a complete record, because no one recorded the words of witnesses who testified in person (as most did).

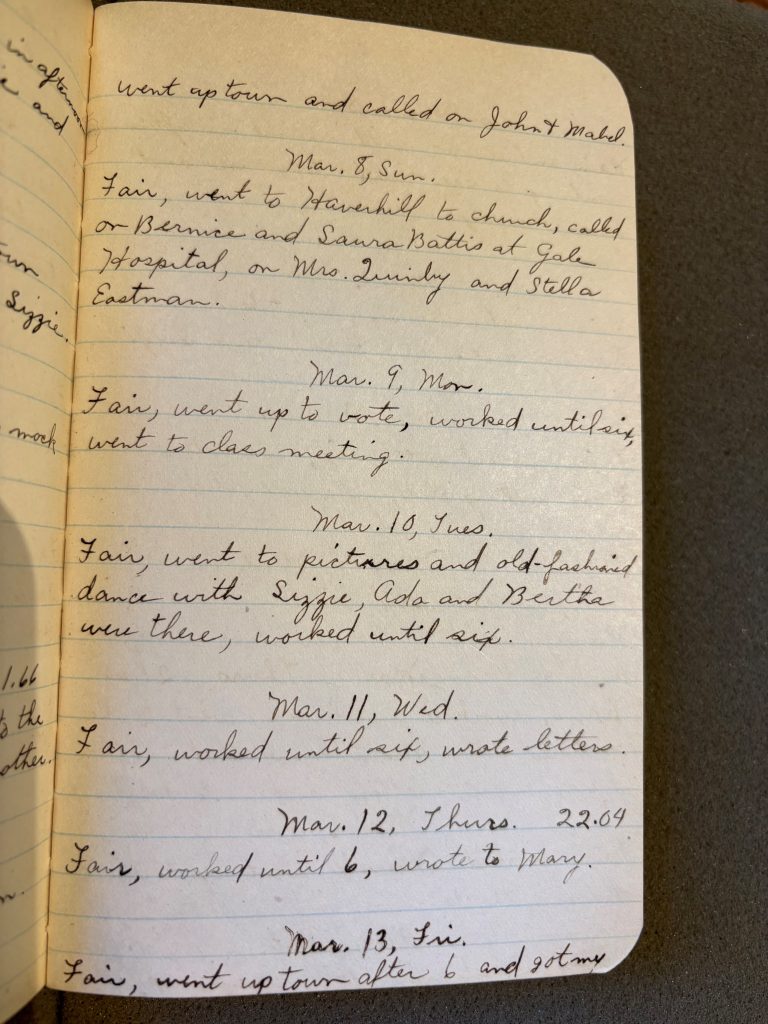

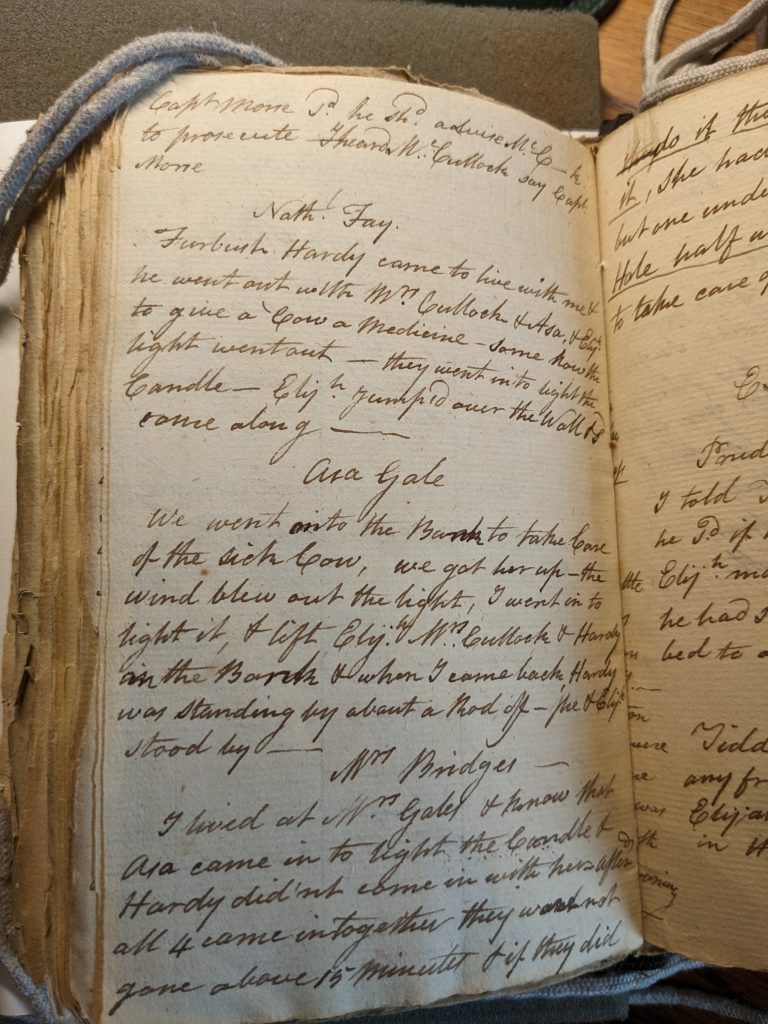

To the rescue come a few eminent judges who kept notes while sitting on the bench. Our scribbling judges focused on naming the deponents (“Mrs. Scott,” “Dr. Mather,” “Sarah Janes”) and summarizing what they said. The MHS houses the magnificent series created by Increase Sumner, kept from 1782 to 1794 in small, sewn notebooks that he called “Notes of Evidence.” At the time, Sumner sat on the Supreme Judicial Court, prior to becoming governor of Massachusetts. His fellow SJC judge Nathaniel Peaslee Sargent maintained a similar habit from 1777 to 1790.

Sumner and Sargent tended to write the most copious notes on oral testimony in serious criminal cases. The appellate court had original jurisdiction over felonies and capital cases. The defendant’s life or future freedom from confinement depended on the outcome. Thus Sumner and Sargent wrote two to six pages on testimony in most murder, manslaughter, infanticide, adultery, arson, assault with intent to ravish, riot, and sedition cases. But civil suits too—such as for ejectment, criminal conversation, and defamation—solicited intriguing observations from subpoenaed New Englanders.

For example, many family members and neighbors testified when Ruggles Spooner of Petersham brought a breach of promise case against a former lover, Sarah Peckam. (Most such cases were brought by jilted women.) Sarah reportedly said she withdrew her consent to marry Ruggles because she “was afraid her father would forsake her.” At other times she claimed her parents would not “suffer” the match to happen and, in that case, “they shall maintain me all the days of my life – I will have no other.” She repeatedly told various friends, “a bad promise is better broke than kept.” Some scenes are worthy of soap operas. A Berkshire County resident with the surname Winchell sued “Esq. Goodridge” in 1782 for depriving him of the sexual and emotional company of his wife of seven years. The Winchells had recently separated. Two male witnesses testified to the dramatic scene that unfolded after Mr. Winchell heard from locals that his wife was having an affair.

Winchell desired me to go [with him one night] & see Goodrich abed with his Wife. (from David Pixley’s testimony, according to Increase Sumner’s notes)

[I] went with Winchell who was in great distress . . . Winchell burst into the bed room [and told] Goodrich to go along. She [Mrs. Winchell] told her husband to get out of her bedroom. They scuffled together. Mrs Ingersoll [who lived in the Winchell house and lodged in an adjacent room, as her husband put it, “3 feet” away] began to read out of the Bible. Goodrich said there was no need of a Sermon. (from Sumner’s notes on Cyrus Papoon’s testimony, with my interpolations and modernized punctuation)

Judges’ bench notes like Increase Sumner’s reveal a lot about the content of courtroom testimony, the social relationships among deponents and the case parties, plus late-eighteenth-century ways of speaking about emotions and household dynamics. We need to remember, however, that they were not full, verbatim transcripts. Starting in about 1800, enterprising publishers began producing a new genre: the criminal trial report. Hawked to the public as cheap pamphlets on selected, sensational trials, these included (to varying degrees of completeness) all parts of the trial—from indictment to ruling or sentence. Court reporters’ use of stenograph machines dates to 1877 in Massachusetts. And yet through all the shifts in note-taking technologies, some judges, including U.S. Supreme Court justices, have found it helpful to keep their own bench notes.

Research Notes:

For the emergence of published trial reports, see Daniel A. Cohen’s study of New England crime literature prior to 1860, Pillars of Salt, Monuments of Grace (1993), espec. Chap 7.

Increase Sumner papers, 1769-1798, Ms. N-1642, Boxes 1 and 2, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Nathaniel Peaslee Sargent Papers, Series 1: Court Minutes, MSS 489, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.

Charles Chauncey, Superior Court Judge in Connecticut 1789-1793, kept extensive notes on testimony he heard. Chauncey Family Papers, Yale University Manuscript and Archives, Mss. Group No. 135, Series VII: Legal Papers, Box 14.

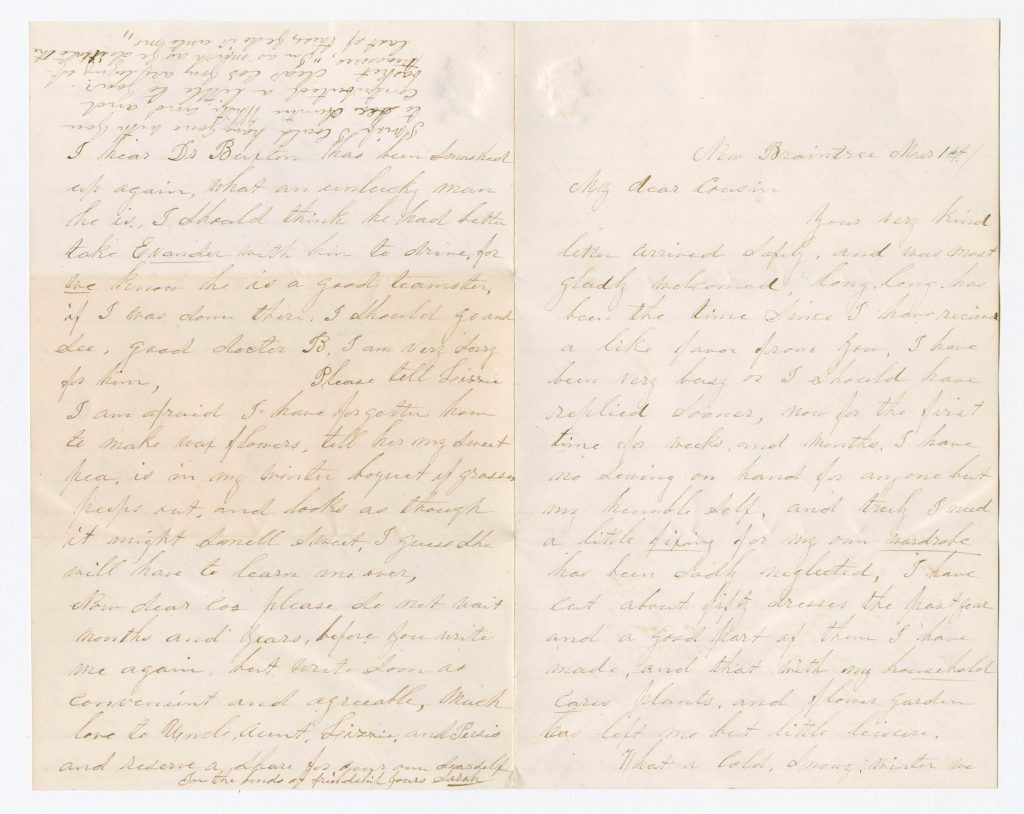

Lawyers often “minuted” courtroom trials when they represented one of the parties. Good examples in MHS collections include many items in the Legal Papers of John Adams and those of Robert Treat Paine. Here is Paine on grand jury testimony leading to the 1782 trial of Priscilla Woodworth for petit treason (killing her husband).

An internet search reveals that SCOTUS justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Harry A. Blackmun kept bench notes. Hugo L. Black’s notes occupied over 600 looseleaf binders; he instructed them to be burned after his death.