by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

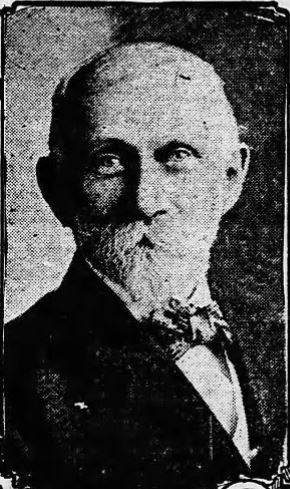

In honor of Election Day tomorrow, I searched the MHS stacks for material related to elections. Unsurprisingly we have a lot! One collection I discovered tells the fascinating story of Charles N. Richards of Quincy, Massachusetts, who, in November 1864, traveled all the way home from Washington, D.C. to vote for Abraham Lincoln.

Richards had served in the 13th Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War, but was mustered out after an injury sustained at Antietam. (He was bayoneted in the jaw.) In 1864, he was 23 years old and working in D.C. at the Senate Stationery Room, the department responsible for supplies. He was a fervent Republican and looked forward to casting his first-ever ballot for Lincoln.

Apparently there was some disagreement over his eligibility to vote in his hometown of Quincy because his mother had been living in Dorchester when he came of age. But when the Quincy town clerk sent him the all-clear, Richards started packing. Unfortunately, though many states offered absentee voting, it was only available to active-duty soldiers. So Richards was going to have to cast an in-person ballot in Massachusetts…about 450 miles away.

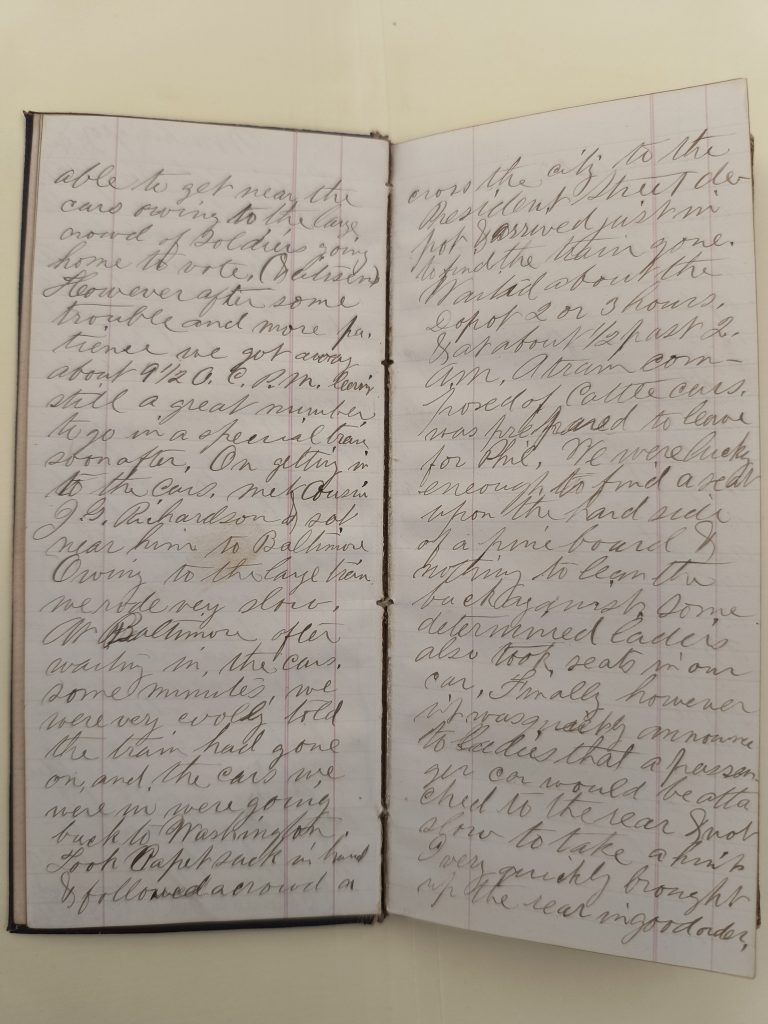

He set off on 4 November, recording every step of the grueling journey in his diary.

First he tried to catch the 6:39pm train to New York, but couldn’t even get near it because of the crowds. Everyone seemed to be heading north for the election. Richards eventually boarded the 9:30 train, but at Baltimore, he was told his car would be re-routed back to Washington. He had to get out and walk to the President Street Depot, but just missed the train there.

Two or three hours later, he caught a 2:30am cattle car to Philadelphia. For part of the ride, he sat on a pine board with nothing to lean his back against, and the rest he spent on the crowded floor of a passenger car. The train reached Philadelphia in the wee hours of the morning in the middle of a snow and hail storm. Richards hopped on a streetcar to Kensington Depot (changing three times) and arrived in time to catch the 4:00am train to New York.

He ferried into New York at 11:30pm, quickly devoured a meal—his first since leaving Washington—and crashed at a hotel for the night. He was so exhausted that he slept through a fire in one of the other rooms!

The next day was Sunday. Richards had a steamboat ticket, but there were no boats leaving until Monday evening. Ever resourceful, he made friends with a hospital steward, who finagled him a spot in his car on the 5pm train to Boston. The steward was escorting a number of wounded soldiers home to vote. When asked who they were voting for, they replied that “they voted the same way they fought.”

After changing trains in Boston, Richards finally reached Quincy at 8:30am on 7 November. His trip had taken a total of 59 hours. Every step of the way, passengers and passersby had discussed, argued, cheered, and nearly brawled about the candidates.

Unfortunately, it turned out the question of Richards’s eligibility was unresolved. Contrary to what he’d heard, the town selectmen were still divided on the issue, and the canvassing committee advised him to play it safe and not vote. Richards took their advice, but was disappointed.

It was really a severe blow to me. It was with great reluctance that I gave up the chance to cast my first vote for such a cause as the Union & such a man as Abraham Lincoln. […] I knew no other home [but Quincy], nor never had, nor never wished to, and now to be deprived of the privileges of a citizen, and cut off from the place I loved & labored for was mortifying in the extreme to me.

In fact, Lincoln won the town of Quincy, surprising his supporters and detractors alike. On his return to Washington, D.C., Richards learned the “glorious” news that Lincoln had carried the day and that “thanks to a kind Providence, the Election passed off in quietude & in order.” He fell asleep “with a light heart.”