by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

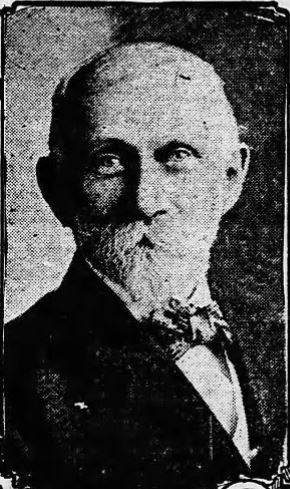

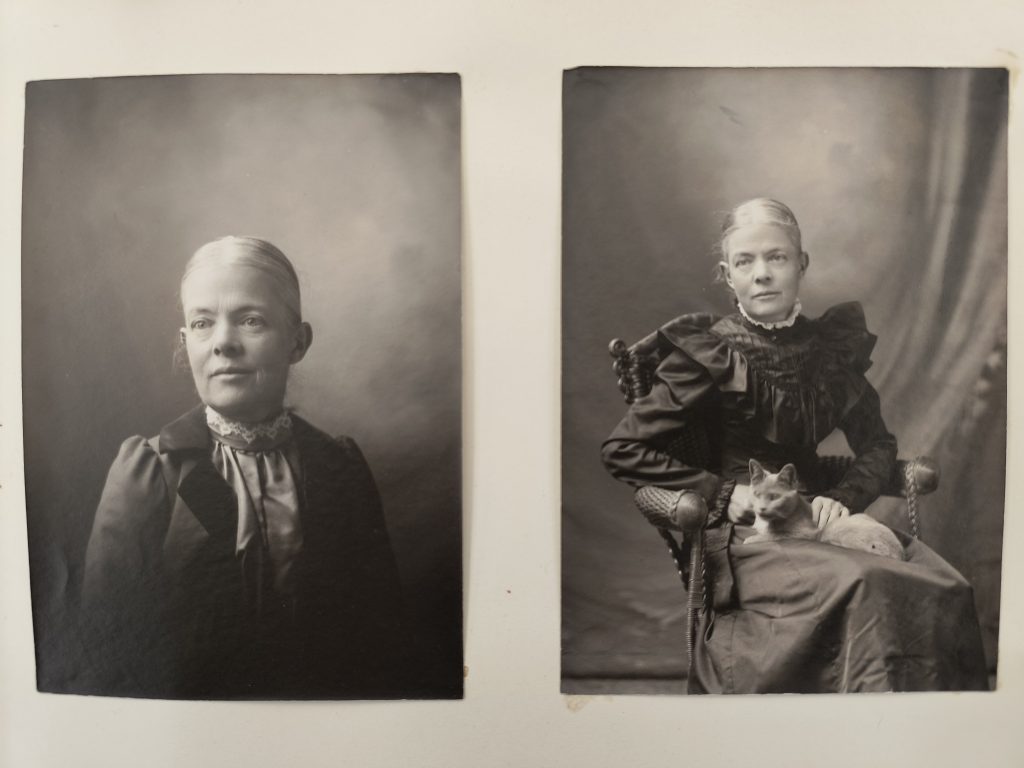

I’m returning today to one of my favorite collections here at the MHS, the Perry-Clarke additions. One of the reasons I enjoyed processing this collection so much was because of all the fascinating people it introduced me to. One of them was Cora Huidekoper Clarke (1851-1916).

Cora was a botanist and entomologist, as well as a teacher, writer, and amateur photographer. Considering the rarity of historical material documenting the lives of women scientists, I was intrigued. Unfortunately, very few manuscripts created by Cora are extant. The MHS and a few other repositories, including Harvard, hold small collections of her personal papers.

Cora was born in Meadville, Pennsylvania, but lived most of her life in Boston. Due to poor health as a child, she was educated at home until the age of 13, but soon made up for lost time. She began studying horticulture at 18, and one of her teachers was renowned historian and horticulturalist Francis Parkman at the Bussey Institution in Jamaica Plain.

It didn’t take long for Cora to make a name for herself in scientific circles. She was a member of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society as early as 1871. She served as head of the science department of the first correspondence school in the U.S. and on the council of the Boston Society of Natural History; published papers in scientific journals, sometimes illustrated with her own drawings and photographs; led the botany group of the New England Women’s Club for 35 years; and, in 1884, was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. And this is only a partial list of her activities and accomplishments.

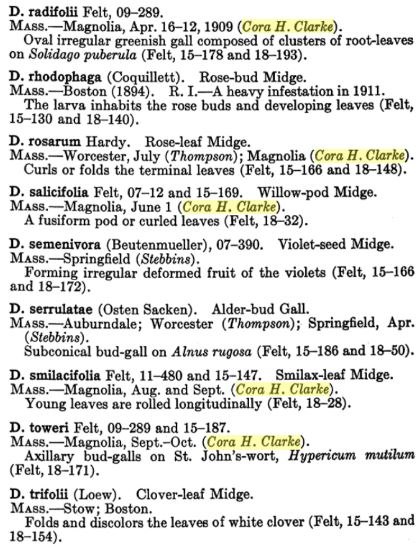

Cora’s specialties included mosses, algae, caddisflies, and gall flies. She was so noted for her success in rearing gall flies that several species have even been named after her. Now, I studied library science, not any of your hard sciences, so it’s all a little beyond me, but I understand enough to be impressed!

Interestingly, even though Cora had the resources to travel widely, her focus tended to be local. In an undated typescript in the collection, she wrote:

I have always been more interested in studying the natural history of a limited and defined area close at hand, than in wandering to new and distant regions. […] In vain my sister tries to coax me abroad; “I have nothing to do in England.” “You can study the flowers.” [“]But I do not begin to know the flowers of New England.” Little Massachusetts holds overflowing riches in her generous hands.

If there’s a theme running through Cora’s writings (at least the ones I’ve seen), it’s the importance of appreciating natural wonders in your own neighborhood, even literally right under your feet. In the same typescript quoted above, she described the beauty of Boston’s urban flora, including plants growing in the Back Bay Fens right next to the MHS.

I particularly like this passage, from a piece by Cora called “Friendly Flowers, or Scraping Acquaintance With Wild Flowers, by a Sub-botanist.”

Plants have this advantage over people, that by studying their parts, we can look them up in a book and ascertain their names, homes, families and peculiarities—have you not often wished that we could do this with people? Perhaps we see the same persons morning after morning passing our house or riding in the same car with us, and becoming interested in them in a friendly way, wish we could look in a book and learn their names, families, homes, occupations? We should doubtless learn things about them quite different from what we imagined must be the case.