by Heather Rockwood, Communications Manager

I sometimes say, “my art history degree did not teach me the history of art, it taught me how to look.” And by “look,” I mean that I have a background knowledge in symbolism, period, style, medium, subject, color, and composition. When I visit museums with friends, I try not to overburden them with interpretation, but perhaps I sometimes do. This skill of looking helps me in my work at the Massachusetts Historical Society. On our social media pages and in our e-newsletters, I am sharing stories from one of the most interesting and important Early Republic collections and archives in the United States. For example, I use my looking skill to find meaning behind the iconography used in art that is a language no longer taught or known to us, except within university classrooms. I thought that for October’s blog, I’d share my looking skills on how to see mourning iconography in the MHS’s collection and archive. Keep reading (or looking!) if you dare!

I would like to start with an interesting embroidery created by Lydia Young Little, circa 1803–1804. At that time, part of a girl’s education would have been embroidery, or another skilled art done while seated, such as quilling or shell-work. An embroidery created by a fourteen- or fifteen- year-old girl signaled that she was properly educated by prosperous parents. Lydia used silk thread and watercolor on silk to create this scene of mourning, which its symbols depict. The urn symbolizes both the corporeal remains of the body and the container of the body’s ashes. The urn is on top of a carved rock slab, which is most likely the grave’s headstone. The wreath relates to the wreath that was often hung on the door of a house in mourning. Even today, a wreath is a common gift to a family who has lost a beloved member. The willow tree, sometimes called a “weeping willow” because the leaves appear to be tears falling from the branches, is also a symbol of mourning. Besides these more obvious symbols are subtle ones, such as the fully closed house in the background. A home’s shuttered appearance was a traditional way to convey a house in mourning. The three children pictured are mourning, but only one, the girl on the left, is actively crying, as shown by her stance on her knees and her handkerchief in her hand. The other two are standing with one hand pointed towards the sky, symbolizing that a family member has passed on to heaven. The last two symbols refer to who has died—the children’s father. The girl on the right holds an anchor symbolizing his seafaring life, and the single ship in the harbor refers to the deceased’s position as a captain. In fact, this embroidery was made to mourn Captain James Little, Lydia’s father.

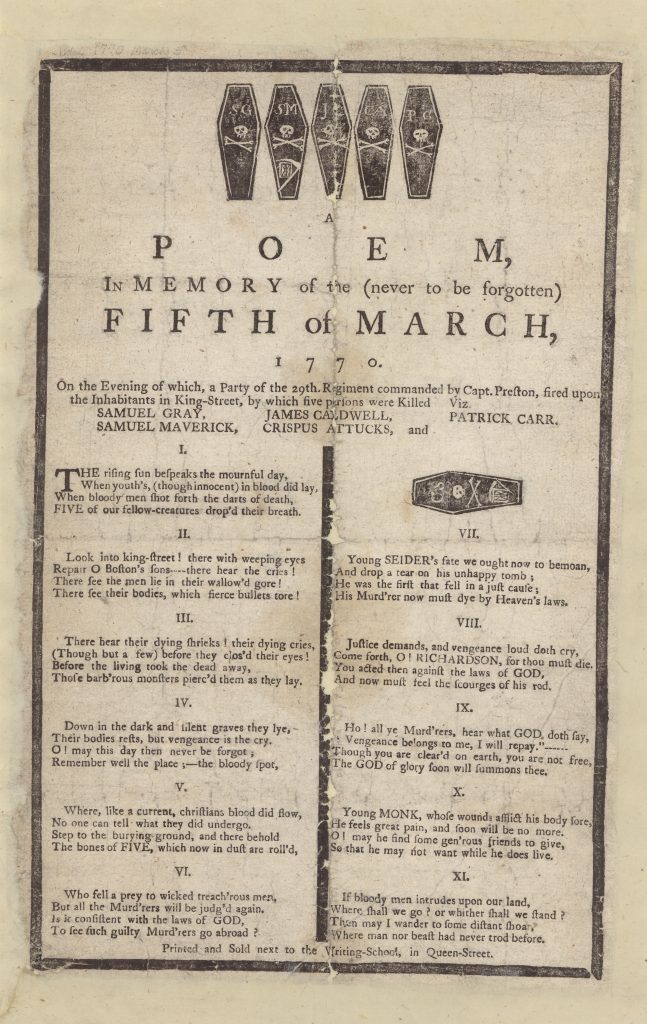

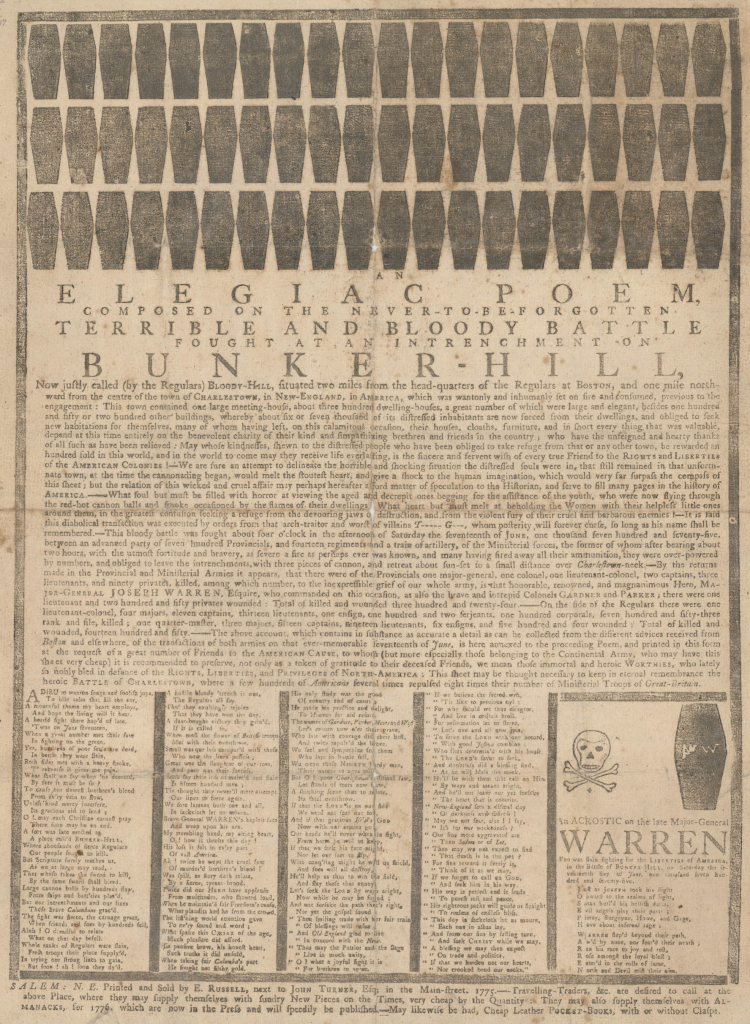

The tale of the Battle of Bunker Hill and the loss of the handsome and charming Joseph Warren is a story I love to tell. This broadside contains an elegiac poem about the battle and an acrostic poem for Warren. Three rows of twenty caskets each illustrate the top of the page—an indication that the first poem is about the death of many individuals. At the bottom right of the page is Warren’s acrostic poem, illustrated by a casket with his initials and a skull and crossbones, the latter a popular symbol of death. Sometimes the skulls have angelic wings, indicating the deceased person has gone to heaven, as also shown in Lydia Little’s embroidery with the children pointing skyward.

Now that you are familiar with mourning iconography, what are some of the symbols you see in the following images, and are there other symbols you see that we didn’t discuss? Have you learned how to look?