by Jordan T. Watkins, Associate Professor, Brigham Young University

The archive inevitably opens unseen roads of research, luring even the most focused historical travelers from their set paths of inquiry. In April of this year, when I again entered the Massachusetts Historical Society, and passed those columns that feel like portals to the past, I had some idea of where (and when) I wanted to explore. And in many ways, I followed the research course I had mapped out. I sought out nineteenth-century sources to include in a documentary edition on slavery and religion. Fairly quickly into my journey, I concluded that the volume would feature printed sources. By using the subject headings of the MHS’s library catalog, ABIGAIL, I compiled an extensive list of sources, which would show how religion was used in the debate over slavery. When I finished my month-long fellowship, I had read numerous tracts, pamphlets, books, and broadsides, made up of various genres, including meeting minutes, letters, declarations, constitutions, petitions, poems, addresses, sermons, personal narratives, and histories. I knew I would never cover the entire territory—even by using the unmatched time machine that is the MHS—but I had traversed a lot of ground, and so I began the selection process.

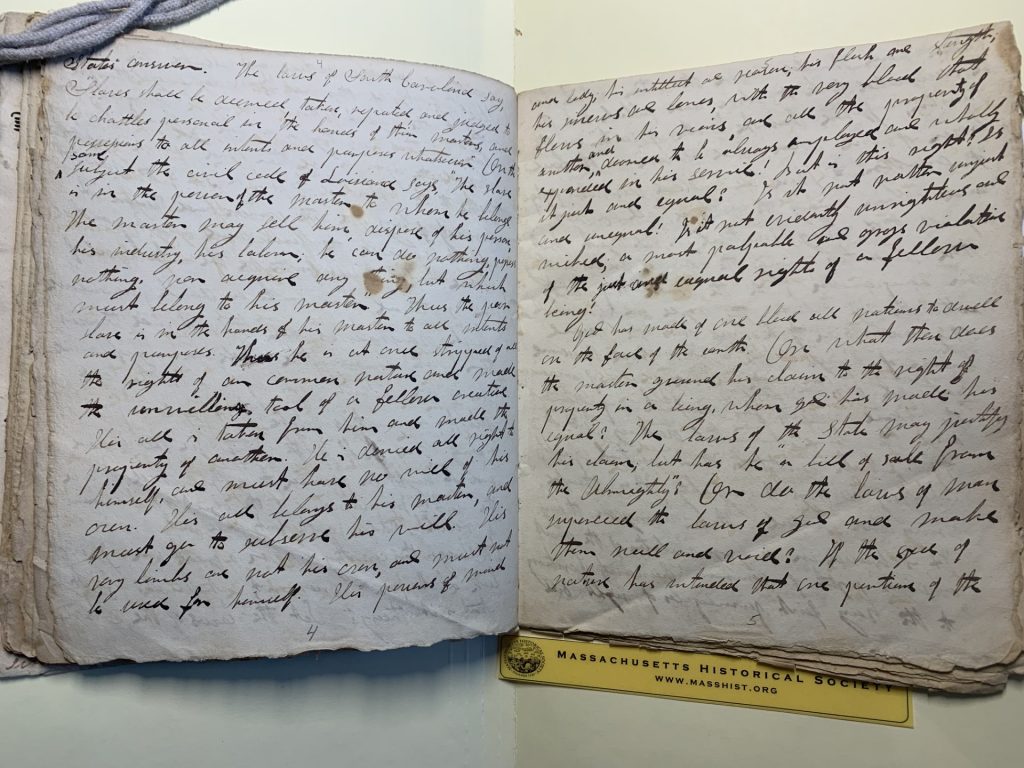

While I sought out printed sources, a few manuscript items caught my attention. The catalog proved instrumental, directing me to an 1836 antislavery sermon given by abolitionist Abijah Cross, pastor of the West Congregational Church in Haverhill. Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist at the MHS, mentioned the sermon in a 2021 post. I suspect that her processing work led to the helpful catalog explanation. As is often the case in my research journeys, I relied on a map created by someone else, which pointed out a historical curio that I would otherwise miss. In the sermon, Cross stated that “slavery in this country is a sin, a great sin,” a conclusion he tied to the biblical passage, “God has made of one blood all nations that dwell on the face of the earth.” Cross’s message corresponded with what I saw in printed antislavery sermons, in which ministers increasingly insisted on slavery’s sin and preached universal humanity based on New Testament teachings. The source served as a reminder that so many sermons never made it into print, even if the message of this particular sermon paralleled what I saw in published sermons.

This was not the only manuscript source I read based on Martin’s processing efforts. I’d guess that Martin’s detective-like work also resulted in the cataloging of a letter written by Nancy Henderson Hubbard Kellogg to her brother Stephen Ashley Hubbard. Through Martin’s sleuthing, she identified the author of the letter, “Nanny,” a teacher who moved to Virginia, and her “Dear Brother,” a journalist in Connecticut. In the 1849 letter, Nancy worried that her brother had caught the disease of abolitionism. She wanted to know, was he “really an abolitionist, a thorough going, downright, abolitionist to the backbone!” The letter demonstrates that even as the antislavery ranks began to grow, many northerners nonetheless continued to view abolitionism as more problematic than slavery. It also shows how the issue of slavery created not only sectional, denominational, and political divisions, but also familial ones.

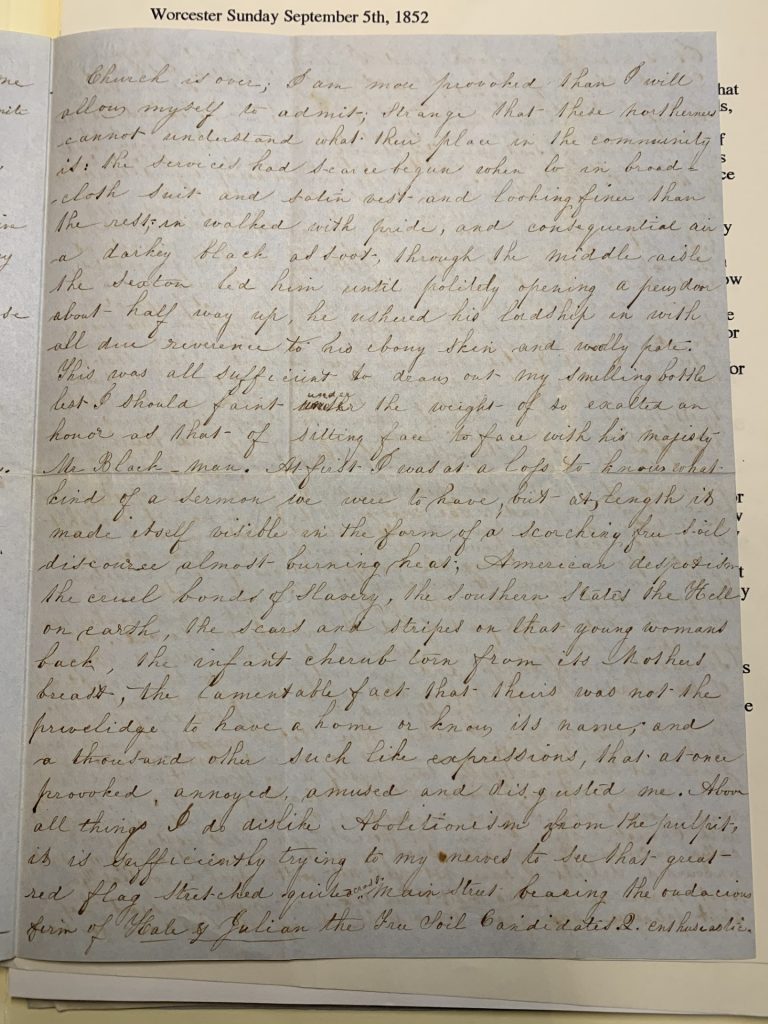

Familial correspondence about slavery also appears in an 1852 letter written by a young woman to her mother, another source I found through the mapping provided in the catalog. In the letter, the daughter complained about a morning Sunday service in Worcester, Massachusetts. Writing that she was “more provoked than” she would “allow [herself] to admit,” she described watching the sexton escort a Black parishioner down the aisle to a seat near her. With heavy sarcasm, the young woman noted the honor “of sitting face to face with his majesty Mr. Black man.” To add insult to injury, she then had to endure “a scorching free soil discourse” on “American despotism[,] the cruel bonds of Slavery, the Southern States the Hell on earth, the scars and stripes on that young womans back, the infant cherub torn from its Mothers breast, the lamentable fact that theirs was not the privelidge to have a home or know its name; and a thousand other such like expressions, that,” she wrote, “at once provoked, annoyed, amused and disgusted me.” The fugitive slave cases of the early 1850s brought slavery closer to home, leading more northern ministers to inject their sermons with narrations of slavery’s horrors. But many of those in the pews rejected such visceral accounts. This 1852 letter is symptomatic of a wider phenomenon: many northern churchgoers opposed antislavery sermons due to racism and their belief that the subject of slavery rested outside the minister’s purview. The young woman much preferred the evening service, at which the minister delivered a more traditional sermon, devoid of “politics.”

These manuscript sources help me see the historical terrain more clearly. In my time traveling, I found numerous printed sermons from the 1840s and 1850s in which more and more ministers attacked slavery. Many of the ministers felt the need to explain why they had chosen to talk about slavery, and many of them also challenged fellow ministers for failing to openly address the topic. After reading enough of these sermons, I began to wonder why so many ministers 1) opened their sermons with a justification for their chosen theme and 2) critiqued the pulpit for failing to address that theme. It seemed to me that the genre of the antislavery sermon was well-established by midcentury, so why all the justifications and critiques? After I spent several weeks reading antislavery sermons, their presence became magnified in my mind and threatened to crowd out other kinds of sources. The above manuscript sources checked this kind of historical mapping, which results from selective research and reading, and allowed me to see more of the nineteenth-century landscape. For all the ministers who addressed slavery, many more avoided the topic. And even if a minister held antislavery views, he likely worried about disapproving parishioners, such as the young woman who wrote to her mother, “Above all things I do dislike Abolitionism from the pulpit.” This 1852 letter, and other similar sources, indicate that anyone telling the story of the antislavery pulpit should attend to the voices in the pews.

My latest sojourn to the MHS archive on Boylston Street and into the nineteenth-century past highlights the value of wandering. It also taught me of another crucial lesson: the adventure of historical research can often feel like a solitary endeavor, but all of us rely on mappings and markings left by others. This should serve as a reminder that these temporal journeys are more communal than we sometimes imagine.