Galen Bunting, Postdoctoral Teaching Associate, Northeastern University, MHS Fellow

As we remember the 79th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, the day US General Douglas MacArthur accepted Japan’s formal surrender aboard US battleship Missouri, we might recall iconic imagery, like the famous Uncle Sam Wants You! recruitment poster, or posters advertising the sale of war bonds. If we imagine what life was like during the Second World War for women in the US, we might remember Rosie the Riveter, whose famous image appeared on a poster to remind American women that they had talents which might help the war effort. But what about the people who paid attention to those messages, the people who worked during the Second World War, then picked up their lives once it was over, without applause or acclaim?

When I think of the real Rosies, working in factories and at the wheels of ambulances, I think of Hilda Chase Foster, born in Brookline, Massachusetts in 1891. As a visiting researcher at the Massachusetts Historical society this summer, I had the chance to read through the letters and documents of Hilda Chase Foster. Her writing includes numerous letters and a self-published memoir—and reveals a woman who was never content to sit idly by during either of the two World Wars.

Joining her brother Reginald C. Foster, who worked in Poland to ensure that orphaned children had food during the war, Hilda crossed the Atlantic during the First World War to serve as a canteen worker. Hilda had applied not just once, but multiple times to work for the Red Cross during the First World War, only to be rejected due to policies against women serving if they happened to have a brother, husband, or other relative in the armed forces. Nevertheless, she arrived in Paris on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, just in time to take part in Armistice celebrations. Hilda felt she was “gadding” about, especially since she had the chance to meet up with friends—as well as her brother Reginald when he visited on leave.

To her relief, Hilda found work in a canteen in Dijon, France that December. There were still American soldiers traveling across France, along with displaced refugees. The Red Cross needed willing hands to serve in their kitchens, providing soldiers with much-needed coffee, muffins, and meals. She later accepted a post in a canteen located in Cochem, Germany.

Reginald wrote to their mother in a letter of April 23rd, 1919:

“When I strongly advocated her coming over here I was terribly torn at heart for I knew what her leaving could mean to you particularly and how you would miss her…only over here could she gain that freedom of old dreads and fears of competition handed down from youthful days…In other words she had to find herself and find herself alone. When I saw her on her way into Dijon last December I noticed a change…she was a different Hilda from when she first arrived in France… there was a light in her eyes, a color in her cheeks, and a jaunty swing to her bearing that showed that she was really finding life through finding herself. I was overjoyed for I felt that my practical certainties were becoming real certainties and that often all was through you would miss her most terribly while she was gone, you would be greatly proud of her when she returned and the joy she would bring would make the months of waiting worthwhile.”

(Hilda Chase Foster Papers 1859-1979, Carton 2, folder 4, Correspondence, Massachusetts Historical Society).

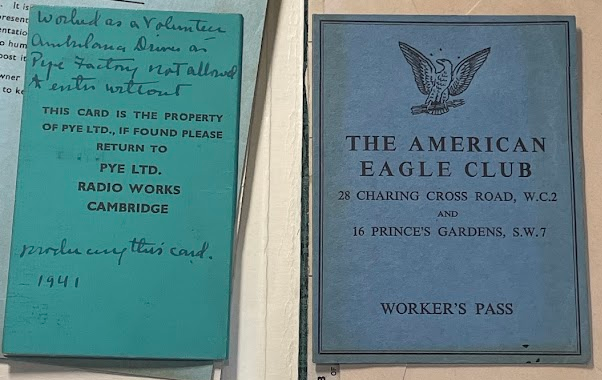

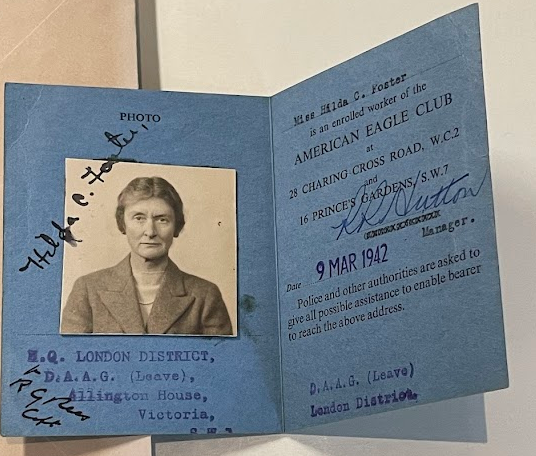

Foster became her own person during the First World War, unlocking a desire to travel: in her memoir, she refers to herself as a rolling stone. When Britain entered the Second World War, she was living in Cambridge, England. Though encountering difficulties due to her alien status, Hilda immediately joined a fire watching squad and wrote to her friends and family for their support to sponsor an ambulance.

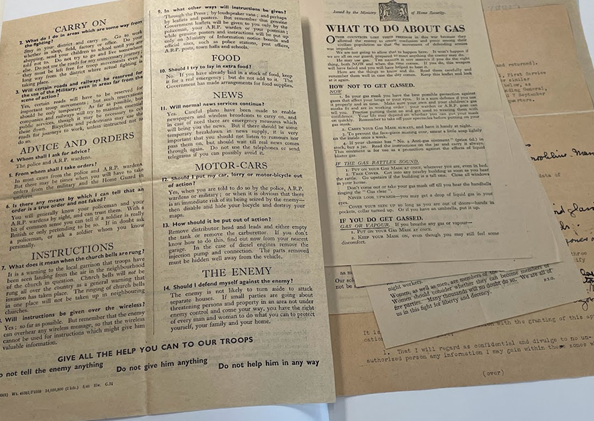

And if that wasn’t enough, she took on the task of driving an ambulance in the Cambridge women’s corps. Her collected documents include training materials for emergency preparation and response, indicating her interest in educating herself in fire prevention and first aid.

To her family, from Cambridge; 1940:

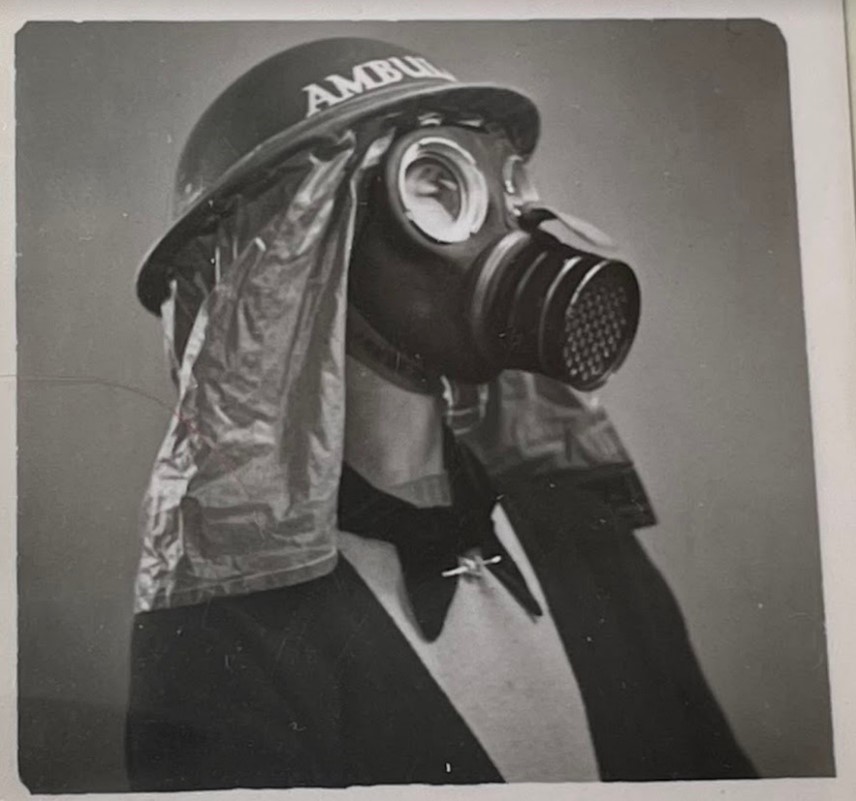

“I had returned to the hotel by 10:30 p.m., bathed and gone to bed when at 1 p.m. the siren started. It had been arranged that all the personnel should report at the first siren so I leapt from my bed still half asleep, pulled on my clothes which have been piled on a chair each night for over a month (trousers, pullover sweater, heavy button-up sweater and coat). I grabbed my tin bucket, gas mask, and map, ran down the stairs, passing in the front hall a group of hotel guests standing waiting, wondering what to do. My bicycle is kept in a shed. Of course in my haste the ‘bike’ caught in a ladder and extra boards, etc., but I finally got started and pedalled up the road passing and being passed by other bicycles also hurrying to their respective jobs. It took me under fifteen minutes from the time of siren to arrival at Russell St. post. I reported to my leader, put on my uniform coat, helped in my job of attending to engines of cars to see they have gasoline, etc., then came inside and lined up on a bench.”

(Hilda Chase Foster Papers 1859–1979, Carton 3, folder 14, World War II Correspondence 1940, MHS, reprinted in Morris, Anne Farlow. The Memoirs of Hilda Chase Foster. Privately printed, 1982.)

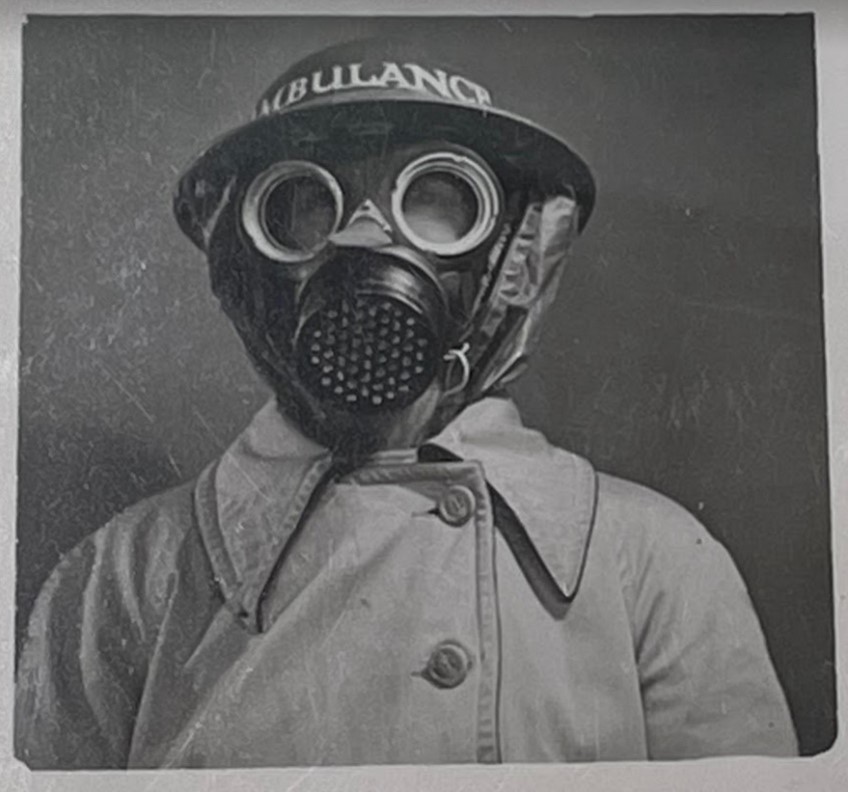

In photos, Foster poses in her gas mask, which she would have worn and kept in working order as an inhabitant of Cambridge during 1936–1942.

When Hilda was able to return home to Boston in 1942, she signed up to work at a rubber factory: her collection includes her union card, passport, with entry and exit stamps, and her notebook, where she scribbled notes during fire watching.

In her study of First World War women writers, Debra Rae Cohen asks, “Is there a safe space for the female citizen?”—and during war, women often experienced terror and danger, even while exercising new independence from their families and traditionally expected roles (p 84). While it might seem contradictory to find identity during world war, Hilda Chase Foster was not alone in embracing her newly found freedom. Carrie Brown’s book Rosie’s Mom: Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War establishes that the Second World War was not the only war where women served. As we see with Hilda, these same women were sometimes active during the First World War as well. And as Kimberly Jensen’s chapter “Gender and Citizenship” in Gender and the Great War (2017, ed. by Susan R. Grayzel and Tammy M. Proctor) shows, “the first world war reinforced the links between masculinity, military service, and citizenship but also offered the possibility for… women of various communities, to claim enhanced civic roles through patriotic service on the home and war fronts.” Hilda Foster continued to live independently, never marrying until her death in 1975, due to a stroke. You can read her memoirs, compiled as a memorial by her surviving family members, in the archives of the MHS.

During the First World War, women articulated their citizenship through helping the war effort, a role which they again held during the Second World War. Such actions, along with new independence gained through traveling abroad, offered young women a real sense of confidence and personal development. The writing, possessions, and photographs of Hilda Chase Foster show that for every idealized Rosie the Riveter, there was a real person, intent on helping the war effort—and finding themselves along the way.

Works Cited

Brown, Carrie. Rosie’s Mom: Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002.

Cohen, Debra Rae. Remapping the Home Front: Locating Citizenship in British Women’s Great War Fiction. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2002.

Hilda Chase Foster Papers 1859-1979, Carton 3, folder 23, World War II Papers, Passports and Certifications, 1940-1945, Massachusetts Historical Society.

Hilda Chase Foster Photographs. Photographer unknown. Includes views of Hilda wearing a gas mask. Box 6, # 143-1762 and #143.1774. Massachusetts Historical Society.

Hilda Chase Foster and Reginald C. Foster, ca. 1918-1919, #143.1721a, Hilda Chase Foster Photographs 1859-1979, Box 6, War Work Photographs, World War I, 1918-1919, various photographs.

Photograph of Hilda Chase Foster, ca. June 1919, in her American Red Cross uniform on a postcard. Hilda Chase Foster Photographs 1859-1979, Box 6, War Work Photographs, World War I, 1918-1919, various photographs, #143.1714.

Jenson, Kimberly, “Gender and Citizenship,” in Gender and the Great War, edited by Susan R Grayzel and Tammy M Proctor. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017. Morris, Anne Farlow. The Memoirs of Hilda Chase Foster. Privately printed, 1982