by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

Today I’d like to continue my series on the Clarke family by telling you about Lilian Freeman Clarke (1842-1921), whose papers can be found here at the MHS in the Perry-Clarke collection and additions, as well as two smaller collections of correspondence and Sturgis-Hooper family papers. Lilian has made a few appearances at the Beehive, most recently in a funny post written by my colleague Hilde Perrin last December.

Lilian was the oldest daughter of Anna Huidekoper Clarke and Rev. James Freeman Clarke of Boston. She was a social reformer and translator. I’ll be focusing on the former in this post.

Two quick clarifications: First, you’ll find her name spelled “Lillian” in many secondary sources, but she and her family consistently used “Lilian,” so that’s what I’m going with. Second, she was actually christened Lilian Rebecca Clarke, but like her aunt Sarah, she adopted the middle name Freeman. This was undoubtedly a nod to her Freeman ancestors, probably especially her step-great-grandfather (great-step-grandfather?) James Freeman, the first ordained Unitarian minister in the United States and an important influence on her father James.

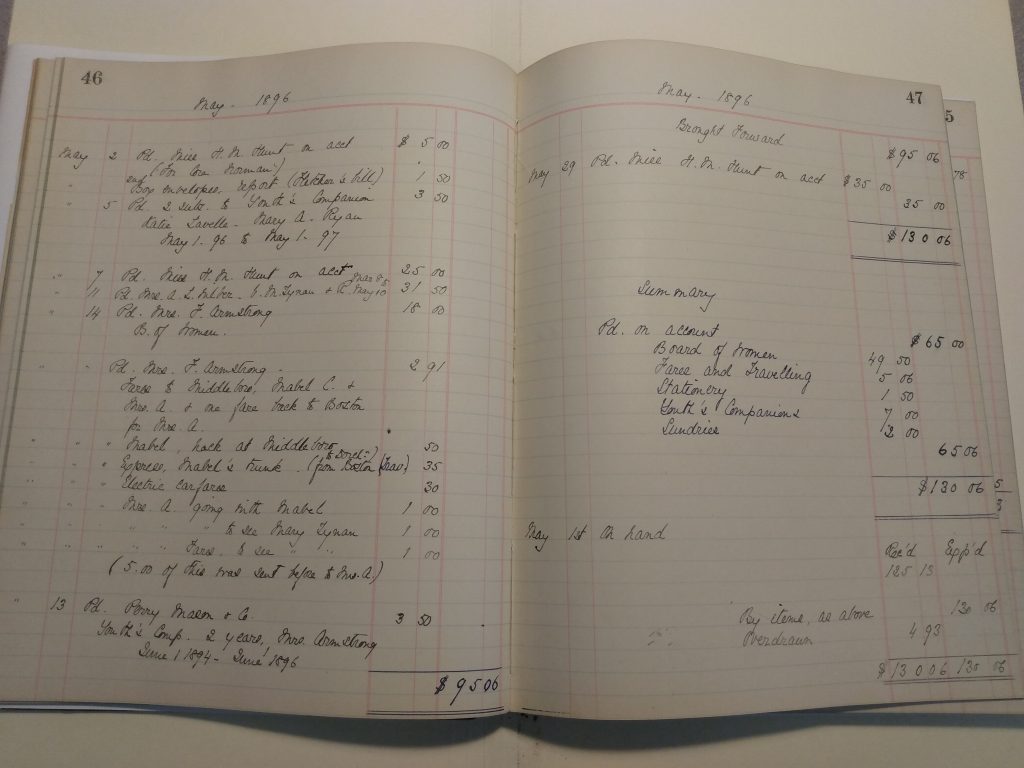

The Perry-Clarke additions, the collection I recently processed, contains family correspondence, personal correspondence, and other personal papers of Lilian F. Clarke. Included is a ledger containing detailed accounts of some of her charitable work between 1895 and 1900.

In 1873, Lilian was concerned about the lack of resources available to new mothers living in poverty. Noticing that “there was in Boston no charity intended to care for infants which did not involve the separation of the mother and child” (from a 1913 report), she and two other women decided to provide direct assistance to these mothers that would allow them to retain custody of their children.

The group was variously known as the Charity (or Society) for Aiding (or Helping) Destitute Mothers and Infants. The two other founders were Dr. Susan Dimock, resident physician at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, and Elizabeth “Bessie” Willard Greene. Tragically, in May 1875, both Dimock and Greene were killed in the wreck of the S.S. Schiller off the coast of England. Lilian was left to shoulder the bulk of the work, though she found a willing and able partner in Mary R. Parkman.

This volume lists expenses for room and board, medicine, milk and food, travel fares, etc. Included are the names of women receiving assistance, as well as Lilian’s charitable partners. For example, Johanna (Pelger) Denecke appears frequently; she was a German immigrant and a widow who apparently boarded many of the mothers and children at her home.

I was impressed by the group’s ability to zero in on a gap in traditional social services, not to mention the individual attention paid to each recipient. Two things were especially important to Lilian: that they worked without institutional bureaucracy, and that they made no distinction between married and unmarried mothers.

Lilian supported various causes during her lifetime. Her obituary in the Boston Globe described her as “a member of almost every organization for the protection of children, and enthusiastic in every movement for the humane treatment of animals.” She also worked with the U.S. Sanitary Commission during the Civil War. She was a suffragist and an anti-vivisectionist. And she donated to victims of the Armenian massacres in the 1890s and the Armenian genocide.

But based on her papers, she devoted the majority of her time and energy to her work with mothers and children in Boston. She was the primary driving force behind the Society for Helping Destitute Mothers and Infants from its founding in 1873 to 1918, when she had to resign because of physical disabilities. The organization disbanded a year later due to lack of funds.

The MHS holds several of the charity’s reports printed between 1875 and 1919. And Lilian herself described its work, particularly the role of Susan Dimock, in “The Story of an Invisible Institution,” published in 1906 in The Outlook magazine. In that article, she emphasized Dr. Dimock’s philosophy: “Think that every patient is your sister. Imagine that you see your own sister in that bed before you.”

On September 25, 2024, join us for a virtual program, Women & Children First: The Trailblazing Life of Susan Dimock, M.D., with author Susan Wilson, and former president of the Dimock Community Health Center Jackie Jenkins-Scott. Register to attend online.