by Lauren Gray, Reference Librarian

Whale tours abound in Massachusetts. In 2024, boats take to the seas laden with tourists white-knuckling smart phones, their eager lenses hoping to catch a glimpse of tail, or a rounded, spurting hump. A native Missourian (read: ‘landlocked’) and new resident of Massachusetts, I took my first whale watch tour in June and was not disappointed. The whales delivered, and my phone was there to catch every hump, spurt, and tail (not to mention a few dolphins). The whale watch got me thinking about the history of whaling. Whaling was a massive industry in the 19th century, and the profits were enormous. But what did that mean to the whales? I’m an animal-lover at heart, and I can’t stand the thought of those giant majestic beauties floundering under a barrage of harpoons, yet that’s exactly what kept the New England economy viable during a critical point in the region’s history. That history has also given us scores of archival material. On further consideration, as it turns out, whaling is the perfect metaphor for America—its greed, violence, exploitation of nature, and human arrogance define one of the worst chapters in American environmental history. (In the west, their quadrupedal cousins, the bison, can tell you the sequel.)

Pilgrims brought whaling to Massachusetts. (Most pre-contact Indigenous people in New England did not actively hunt whales.) Spying a pod of whales during a voyage from Plymouth to Cape Cod in 1621, Edward Winslow commented, “…every day we saw whales playing hard by us, of which in that place, if we had instruments and means to take them, we might have made a very rich return, which to our great grief we wanted.” [1] He went on to report that, had he the right tools for the job, he “might have made three of four thousand pounds worth of oil” out of the whales, and “purpose the next winter to fish for whale here.”

However, it would be another two decades before there was wide-spread commercial whaling in the colonies. By the 1670s, small whaling ships, crewed by English and Indigenous people together, hunted off the coast of Cape Cod. Even before the end of the 18th century, scarcity in the whale population in the northern Atlantic forced whalers to round the horns to hunt for whales in the Pacific, where an ocean of opportunity awaited. The golden age of whaling had begun.

Golden, that is, for the sea captains, merchants, and bankers who lined their pockets from the spoils of the hunt. In the first half of the 19th century, American whalers dominated the global market, and the whaling industry contributed $10 million dollars to the U.S. GDP (which is over $300,000,000 in 2024 dollars).[2] Whale oil, made from boiled blubber, spermaceti from sperm whales’ heads, and baleen—the delicate bristles found in baleen whales’ mouths—were key resources for the Victorians. Baleen was woven into the corsets that pinched the waists of tubercular maidens and buxom madams alike; whale oil burned in lighthouses along every coast; and spermaceti wax dripped and flared in candles that illuminated nights “lit only by fire.”[3] In the Victorian world, the whale was omnipresent and indispensable.

If it was fantastically lucrative for the merchants profiting from their ill-begotten wares, it was not so fantastic for the whales. During whaling’s heyday, the whale population plummeted. Due to the steady decrease in whale populations and the advent of viable alternatives (like manufactured gas and petroleum), the American whaling industry went into a steep decline, and effectively ended in the mid-1880s.[4] While scholars disagree on exact numbers, over 150,000 whales were killed in just 50 years of whaling’s heyday, leading to the decimation of the blue, right, gray, and bowhead populations.

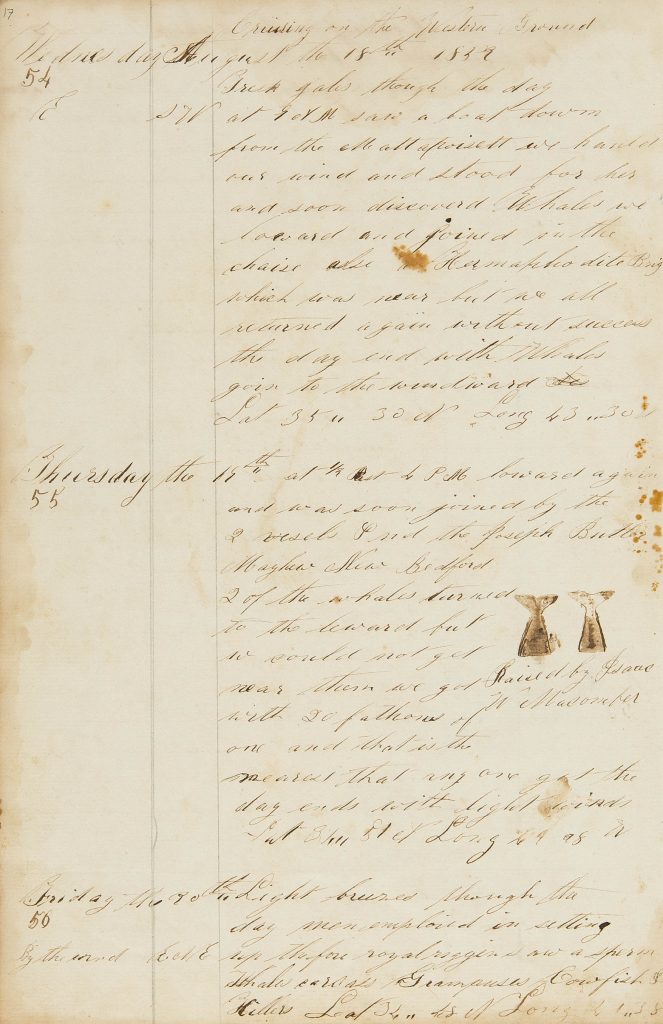

In the historical record, whales don’t fare much better. After my whale watch tour, I came back to the MHS to start research on this blog post, but I found that whales surface in the MHS catalog rarely and even then, the archival record captures them as creatures to be hunted and exploited. The MHS holds dozens of ships logs, descriptions of whaling voyages, personal papers of those who participated in the whaling industry or profited from it, histories of the towns where whaling dominated, and much more. But where, exactly, are the whales that make whaling possible? In the archive, the pictures that come down to us are grainy and grim: a boy perched next to a beached and conquered finback; a sun-bleached skeleton of indeterminate species, dreary in sepia; a captive beluga in the Boston Aquarial Gardens flashing through a young girl’s diary “white almost as snow.” In the archive, the whales’ memory is entwined with the legacy of violence and greed, the hunters’ hubris immortalized in ledgers and statistics.

The history of whaling is, in large part, the history of New England. Thankfully, the industry collapsed before irreparable harm could be done. Whale populations rebounded throughout the 20th century, and now the ‘gentle giants’ are objects of awe instead of greed. Just this month, amazed Bostonians were greeted by a breaching whale in Boston Harbor, and local institutions like the New England Aquarium are at the forefront of conservancy and education. However, despite whales’ popularity, and the efforts of environmental groups and advocates, whale populations continue to be disrupted by illegal whaling; shipping lanes interfere with mating patterns; and global warming makes whale feeding grounds unstable. Edward Winslow’s “great grief” in 1621 was that he could not hunt the whales; in 2024, it’s that the colonists eventually succeeded. Meanwhile, in the archive, we are left to grapple with whaling’s history. Whaling’s economic benefits alone fill volumes, and the data found in ships logs and ledgers help us to understand our changing climate. Stories from whaling voyages help us to better understand the human condition.

I wish it was as simple as balancing the karma between history and what we can learn from it. All I can think is, “tell it to the whales.”[5]

[1] Edward Winslow, Mourt’s Relation (1621)

[2] Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Teresa D. Hutchins, “The Decline of U.S. Whaling” (The Business History Review, Vol. 62, No. 4, Winter, 1988 pp. 569-595)

[3] William Manchester, A World Lit Only by Fire (Little, Brown and Company, 1993)

[4] Whaling globally didn’t peak until the 1960s.

[5] Max Brooks, World War Z (Three Rivers Press, 2007)