by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

I wrote for the Beehive a few weeks ago about a collection I’d just finished processing, the Perry-Clarke additions, which documents the lives of several generations of the Clarke family of Boston. The family member probably best known to most people is Unitarian minister James Freeman Clarke. But I’d like to use my bully pulpit here to tell you about some of his equally impressive relatives. This post will be the first in a series.

I’ll start with my favorite, James’s older sister Sarah Freeman Clarke. Sarah’s life spanned almost the entire 19th century, from 1808 to 1896. She was primarily a landscape painter, a student of artist Washington Allston, and her artwork was exhibited throughout Boston during her lifetime and even at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. But she also taught classes at the Temple School, wrote articles for publication, and even founded a library in Marietta, Georgia. She traveled widely, and her network of friends included Ralph Waldo Emerson; Elizabeth, Mary, and Sophia Peabody; and Margaret Fuller. In fact, Sarah illustrated Fuller’s book Summer on the Lakes in 1843 and participated in Fuller’s famous “Conversations.”

Though a professional success by anyone’s definition, Sarah was also devoted to her family. As a young woman, she helped her mother run a boarding house. In later life, she moved to Georgia to live with her brothers as they all aged and needed mutual support. She doted on her nieces and nephews, corresponding with them frequently. She and her brother James were especially close, and she was a great—and I think underestimated—influence on his career. Her letters are full of encouragement, advice, and constructive criticism.

The first ten boxes of the Perry-Clarke additions consist of family correspondence, and next to James and his wife Anna, Sarah is the third most frequent correspondent. The collection also includes one box of Sarah’s personal papers. Another collection at the MHS contains a diary she kept on a Nile voyage in 1873-1874. For information about that volume, see this excellent post written by a colleague of mine back in 2019.

When archivists are processing manuscripts, there just isn’t enough time to read everything; we usually have to skim. Sarah’s were the letters I most wanted to read. She wrote well, not in that formal, flowery style some of her contemporaries used. Her letters are more colloquial. She expressed her opinions frankly, but in a humorous, self-deprecating way. For example, when James misattributed an article in The Dial to Sarah (actually written by Fuller), Sarah teased him, “You say well that I must have made vast progress to do that. Truly I must have out-travelled myself & become another person first.”

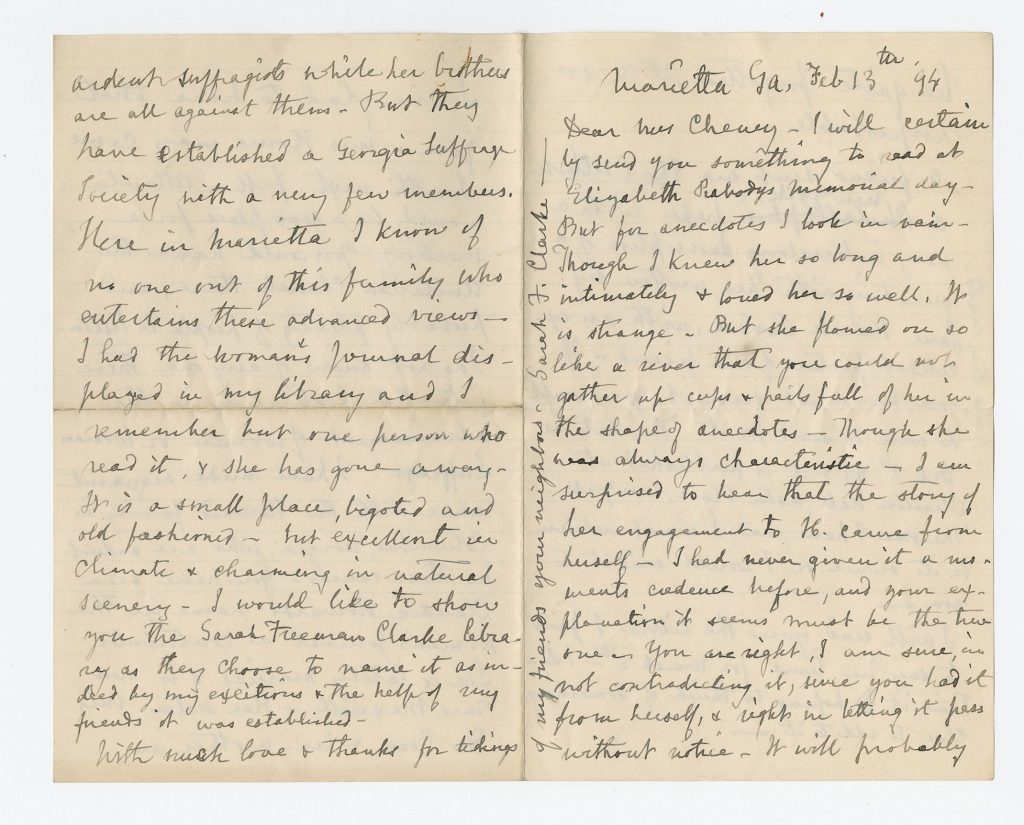

Sarah’s letters from Georgia in the closing decade of the 19th century are fascinating for another reason: women suffragists were trying to make inroads in the state. Sarah was particularly impressed by the Howard sisters of Columbus, including Claudia Howard Maxwell, Miriam Howard DuBose, and Helen Augusta Howard. The Howards were fighting for women’s rights in a very hostile climate, against, in Sarah’s words, “bigoted and old fashioned” men, attacks “from the pulpit & press,” and even the “violent” opposition of their own brothers.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association held their 27th annual convention in Atlanta in 1895. The 87-year-old Sarah had hoped to attend but was unable. Regarding women’s suffrage in Georgia, she wrote:

The few people whom I know to be in favor of equal Suffrage are strenuous in their belief and urgent in their practice amid much opposition from those who think the Bible forbids any such unnatural doings by women. There is much ancient superstition here, of the same sort as that which claimed that Slavery was a biblical institution, and that the negroes were more benefitted than injured, by being torn from their homes & brought here to be slaves, because – it gave them a chance to become Christians! Such is this queer world!