by Heather Rockwood, Communications Manager

Faneuil Hall was built in 1742 by Peter Faneuil, (1700–1743), a man who inherited the estate of his uncle, but then grew to be one of the wealthiest men in Boston, using his business acumen as well as benefits from the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Faneuil gifted the building to Boston for use as a town meeting hall and marketplace. In the years before the American Revolution, the building was the scene of many incendiary speeches by liberty-seeking Bostonians, including Samuel Adams and James Otis Jr. The building continued to be used for town meetings until 1822, after which it was a thriving marketplace through the 1800s and early 1900s, while continuing to be a place for speech-making for Abolitionists. By the 1960s the building fell into disrepair but became a National Historic Landmark and went through renovations in the 1970s and 1990s. One of the more interesting aspects of Faneuil Hall is its copper weathervane in the shape of a grasshopper, created by Shem Drowne in 1742. In the map below from 1776, “D” marks the location of Faneuil Hall.

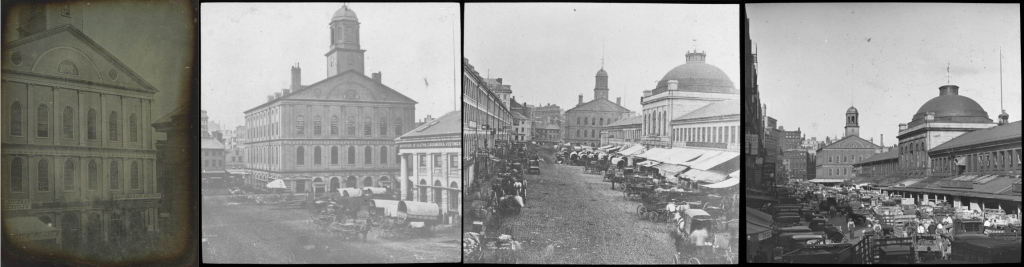

The MHS has a large collection of photographs and a few engravings of Faneuil Hall throughout its 282-year history. The first image, an engraving, is from 1789. Its most notable features are the building’s central cupola, the three windows across the west side, and two floors, all of which changed in 1806 when Charles Bullfinch added floors, widened the building, and moved the cupola to the back, east side.

I grouped the following photographs into similar views of the building, showing how some are eerily similar but from different time periods. The first group shows views of the front of the building, or east side.

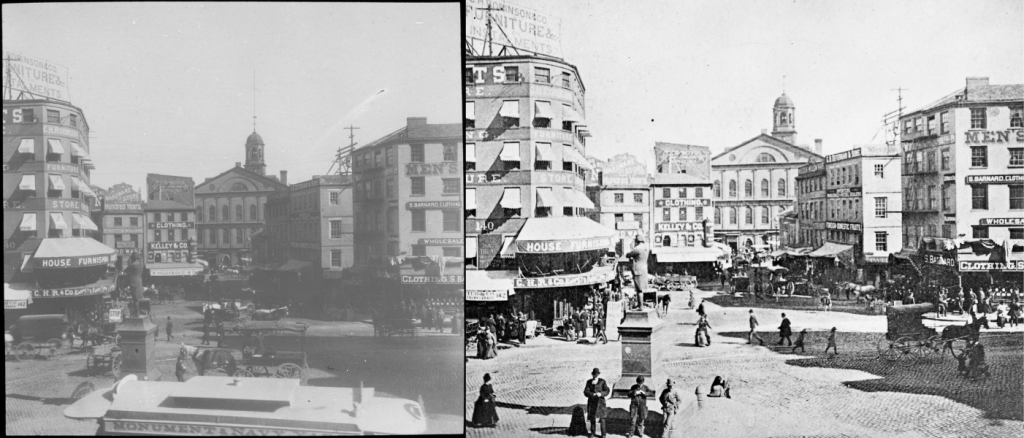

The second group shows Faneuil Square, or Adams Square, now Dock Square, in front of Faneuil Hall.

The last group of photographs captures the backside of Faneuil Hall, as well as the other end of Quincy Market on the south side, or South Market. You may notice that the first image on the left is flipped—try reading the signs—it is also the oldest photograph.

This last photograph was taken from the north side of Faneuil Hall, but looks eastward, with a focus on Quincy Market behind it.

Something I am excited to see in the MHS collection is the Ben and Jane Thompson Faneuil Hall Marketplace Records that relate to the restoration and revitalization of the Faneuil Hall Marketplace area, including Quincy Market and the North and South Market buildings. The collection includes all the records for the planning, construction, and opening stages of the project, as well as correspondence from preconstruction and post-openings. Publicity and visual materials also comprise the collection, all yet to be digitized, but you can request to view it. Learn more about how to visit the MHS and see documents and collections like this.