by Rakashi Chand, Reading Room Supervisor

Can I tell you a story? A story that will transport you to the court of Tsar Nicholas II and the Meiji Regime, gilded carriages, opulent palaces, and a war between superpowers, that ends in Portsmouth, NH, USA.

The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) was primarily fought over Russia’s expansionist policies in East Asia, with major battles occurring both at sea and on land. Japan emerged victorious over Russia, marking the first time an Asian power defeated a European power in modern history, setting the stage for Japan’s future imperial ambitions and exacerbating internal political unrest growing in Russia. President Roosevelt made it his personal mission to bring peace to the two empires, eager for America to take its place as a world power player.

Getting both sides to the negotiating table at the neutral location of Portsmouth Naval Yard, straddled between New Hampshire and Maine, proved to be a daunting task. Roosevelt hand selected George von Lengerke Meyer, a Bostonian serving as the US Ambassador to Italy, for the very special mission of negotiating that peace, and reassigned him to the court of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia. The George von Lengerke Meyer Papers detail the Russo-Japanese War from the Russian perspective and Meyer’s extensive peace negotiations with the Russian Tsar and government.

Roosevelt writes to Meyer on December 26, 1904, from the White House (Received by Meyer on January 20, 1905, in Italy)

“Dear George,

This letter is naturally to be treated entirely confidential, as I wish to write to you freely. I desire to send you as ambassador to St. Peterburg. My present intention is, as you know, only to keep you for a year as Ambassador, but there is nothing certain about this inasmuch as no man can tell what contingencies will arise in the future, but at present the position in which I need you is that of Ambassador at St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg is at this moment, and bids fair to continue to be for at least a year, the most important post in the diplomatic service, from the standpoint if work to be done, and you come in the category of public servants who desire to do public work, as distinguished from those whose desire is merely to occupy public place – a class for whom I have no particular respect. I wish in St. Petersburg a man who, while able to do all the social work, able to entertain and to meet the Russians and his fellow-diplomats on equal terms, able to do all the necessary plush business – business which is indispensable can do in addition, the really vital and important things. I want a man who will be able to keep us closely informed, on his own initiative of everything we ought to know, who will be, as an Ambassador ought to be, our chief source of information about Japan and the war – about the Russian feeling as to the continuance of the war, as to the relationship between Russia and Germany and France, as to the real moaning of the movement for so-called internal reforms, as to the condition of the army, as to what forces can and will be used in Manchuria next summer, and so forth and so forth.”

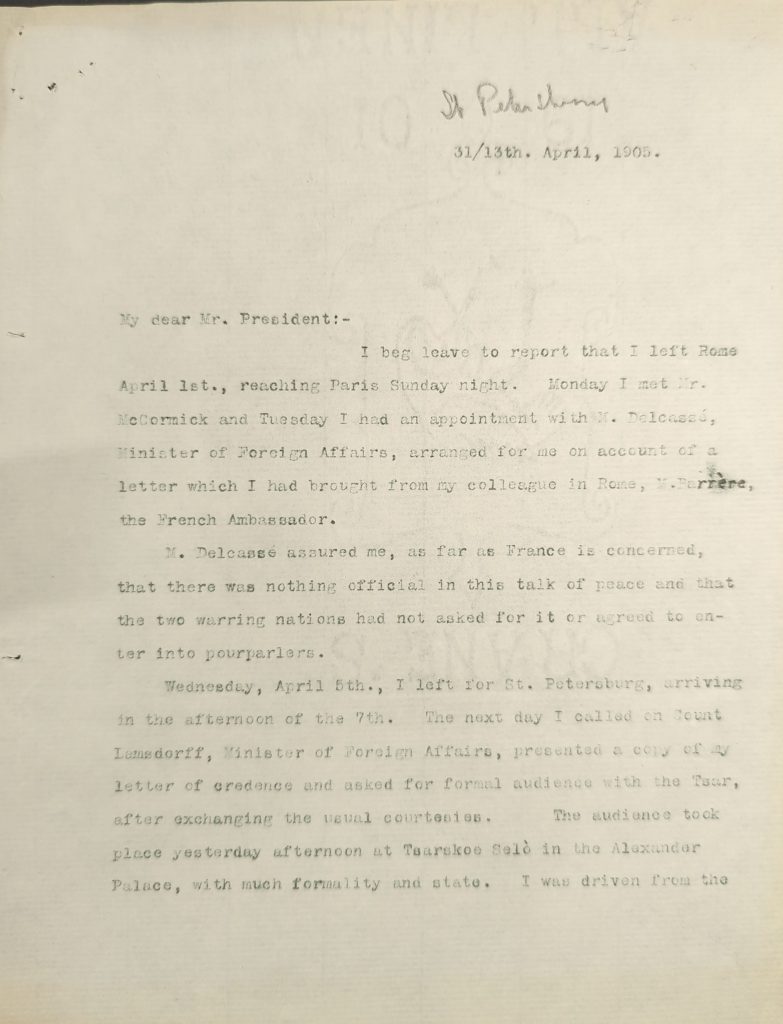

Arriving in St. Peterburg on April 7, 1905, Meyer sought an audience with the Emperor of Russia, Nicholas II and after being presented at court, Meyer wrote to Roosevelt on 31/13th April 1905:

“Mr. Delcasse assured me, as far as France is concerned, that there was nothing official in this talk of peace and that the two warring nations had not asked for it or agreed to enter into pourparlers.

Wednesday, April 5th, I left for St. Petersburg, arriving the afternoon of the 7th. The next day I called on Count Lamdorff, Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented a copy of my letter of Credence and asked for formal audience with the Tsar, after exchanging the usual courtesies. The audience took place yesterday afternoon at Tsarskoo Selo in the Alexander Palace, with much formality and state. I was driven from the station I a gilded coach with six white horses. My first presentation was to the Dowager Empress, (Sister of the Queen of England), and ten minutes later I was received by the Emperor and Empress. I had hoped I would see the Emperor alone, as the English Ambassador had told me that the young Empress was influencing her husband to continue the war and gain a victory.

I delivered your instructions as cabled by Adee on March 27th, and she drew nearer and never took her eyes off the Tsar. When I pronounced the words “at a proper season, if the two waring nations are willing, the President would gladly use his impartial good offices towards the realization of an honorable and lasting peace, alike advantageous to the parties and beneficial to the world,” His majesty looked embarrassed and then said: “I am very glad to hear it.” but instantly turned the conversation on to another subject, never alluding it to it again.“

Convincing the Emperor and, more importantly, the Empress, was not going to be easy.

On June 12/1, 1905, Meyer writes to Mr. J. Morris Meredith: “They are tremendously shocked by their naval defeat here, but are not even yet talking peace. What they are demanding through the press is a call of the promised Representative body, in order that they may get an expression of opinion from the people direct whether the war should continue or not.” It would take a lot of convincing on Meyer’s part to make the Emperor and Empress realize the effort to continue the war was futile, but in the end he succeeded. Japan was optimistic that Russia would acquiesce based in the expense and political unrest the war was causing.

Roosevelt writes to Meyer on June 19, 1905:

“In my efforts I have been actuated by an earnest desire to stop bloodshed, not merely in the interest of humanity at large and in the interest of other countries, but especially in the interest of the Russian people for I like them and wish them well.

You know Lamsdorff and I do not. If you think it worthwhile, tell either him or the Czar the substance of what I have said, or show them all or parts of this letter. You are welcome to do it. But use your own discretion absolutely in this matter.

Russia has not created a favorable impression here by the appearance of quibbling that there has been over both the selection of the place and over the power of the plenipotentiaries whom Russia will appoint. It would be far better if she would give the impression of frankness, openness and sincerity.”

The envoys of Imperial Japan and Imperial Russia arrived in Portsmouth on August 9, and the Treaty of Portsmouth was signed on September 5, 1905. Roosevelt won the Nobel Peace prize for his success in bringing both sides to the negotiating table. On September 1, 1905, Roosevelt finally writes to Meyer, as the negotiations are settled in Portsmouth:

“Dear George,

It seems to me that one of the crucial points in securing the peace was what you finally did in your conversation with the Czar when you persuaded him that the southern half of Saghalin would have to be surrendered to the Japanese. Of course while I was cabling to you messages for the Czar I was also doing what I could with the Japanese Government…

(and concludes the letter with)

Well, apparently we have carried the thing safely through, but it has not always been plain sailing.

Faithfully yours,

Theodore Roosevelt”

Dive further into the Meyer Papers to be transported to Imperial Russia on the brink of chaos and experience the effort to bring a peaceful end to the Russo-Japanese war.

Portsmouth is a beautiful city by the sea, featuring cobblestone streets lined with gas lanterns and the historic homes of sea captains and merchants. Whenever I visit Portsmouth, I look out at the ocean and imagine what a sight it would have been to see the arrival of vessels from Imperial Russia and Imperial Japan in August of 1905.