by Susan Goodier, PhD, MHS Fellowship, 2023–2024

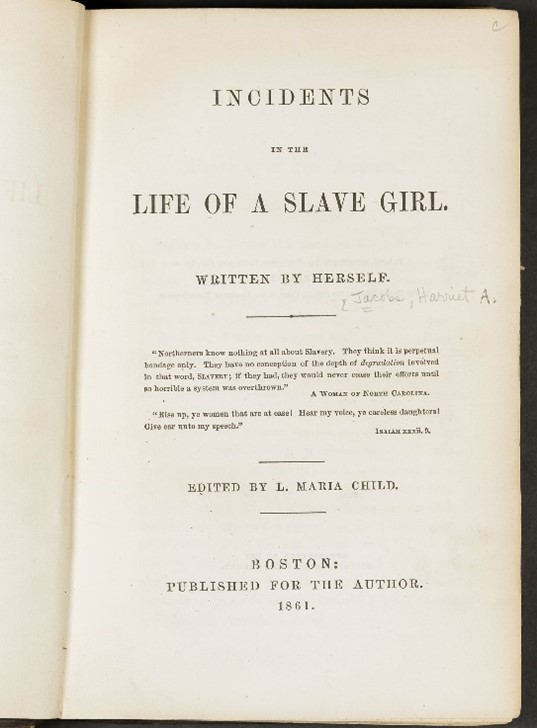

When I began my fellowship at the MHS, I did not plan to find much in the collections about Louisa Jacobs (1833–1917), the subject of my research project. I was there to research the people she knew, especially in the African American community of the Boston area. Louisa Jacobs has previously only been a minor character in the writings about her mother, author Harriet Jacobs (1815-1897), who wrote Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861).

Kate Culkin, Jean Fagan Yellin’s Associate Editor for the Harriet Jacobs Family Papers (2008), once told me that “Louisa Jacobs was like a ghost—very difficult to find.” The comment struck a chord; my research for a biography of Louisa Jacobs seems a bit like ghost hunting. I see hints or tantalizing details, but little to add to what has already been found. Gradually, however, a more comprehensive understanding of Jacobs is emerging for me.

Louisa Jacobs is everywhere in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, because her mother wrote about her daughter, using the pseudonym, Ellen. I began reading Incidents my first day as a Fellow at the MHS in 2023. Purchased in 1911 by the Society and inscribed “April 2, 1864” on the flyleaf, the book had once been owned by J. W. Clarke (perhaps John Willis Clarke, who wrote The Care of Books in 1901). Reading in the quiet comfort of Ellis Hall Reading Room makes me part of a shadowy community of people who over the course of 163 years have also read this very copy of the Jacobs’s family story.

Jacobs was more elusive in the sources of people she knew; many of them ghosted her. For example, in sixteen volumes of the diaries of Robert A. Boit, who married Lilian Willis, a member of a family deeply connected to Jacobs for over fifty years, he detailed his life and glued in his correspondence. He noted he took tea with Louisa Jacobs twice, but barely discussed her otherwise. He waited until her death to write, “She had great intelligence, a rare fancy & imagination, and a way of expressing herself that was quaintly and delightfully her own. Her letters were always interesting in their graceful and quite unusual turns of thought and of expression.” Did he save any of her letters? Not one.

Another example of ghosting appears in the collection of Reverend Samuel May, Jr., a Garrisonian abolitionist. May and his wife, Sarah, visited so-called “contraband camps” for freedpeople during the Civil War. They visited the Jacobs School in Alexandria, VA, where Louisa Jacobs taught. Did Samuel May note the visit in his memorandum book? No. Based on a letter Louisa wrote to Sarah May, published in the February 1865 National Anti-Slavery Standard, the Mays had continued soliciting donations for the school. But the Mays did not record their efforts.

One more example of ghosting Louisa Jacobs. In May 1865, Jacobs traveled with Hannah E. Stevenson and other women to Richmond, VA to distribute clothing. Stevenson was the first woman from Boston to volunteer to serve as a nurse, and the MHS has a collection of her wartime letters to family members. Stevenson didn’t mention the Jacobses in any of her letters home that month. She redeemed herself, however, when she worked as secretary for the Boston branch of the Freedmen’s Union Commission. At the Boston Public Library, I recognized a previously unidentified fragment of a letter as having been written by Stevenson, who commented that Louisa Jacobs had stopped by the office, “looking pretty and well.”

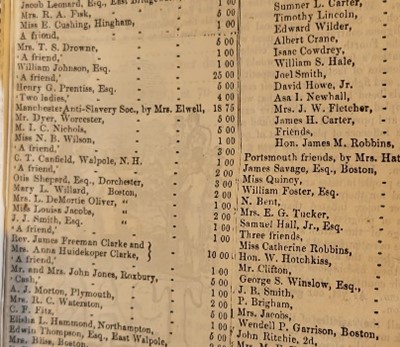

That’s what is so invigorating about this quest; I find Louisa Jacobs in unexpected ways. From a Garrison family scrapbook, I learned that Jacobs donated $2.00 (approximately $75 today) to the anti-slavery cause.

In other sources I got a sense of William Cooper Nell, an African American historian who helped integrate Boston schools in the 1850s. The MHS has an edited collection of his letters; he hinted of his romantic interest in Louisa Jacobs in letters to Amy Kirby Post. I also traced the teaching careers of Jacobs’s friends, sisters Virginia and Mariana Lawton, in the Freedmen’s Record, and I built an understanding of the African American community Louisa Jacobs inhabited in the Boston and Cambridge areas from numerous sources available at the MHS.

The staff of the research department enhances the extensive collection of books, diaries, manuscripts, and artifacts. They found answers to questions such as those I had about stage sleighs, religion, and nineteenth-century maps and publications. They also connected me to scholars and archivists who continue to help me recreate the world Louisa Jacobs inhabited. The woman who was once a ghost is materializing as personable and imaginative, deeply loyal to her friends and her community. My sojourn at the MHS helped make this possible.