by Isabella Dobson, PhD Student at Boston University in History of Art and Architecture

Viewing the miniature mourning portrait of Jane Winthrop is just as much a tactile experience as a visual one. Undoing the tiny clasps and folding open the case reveals an interior lined with satin and velvet and offers a tangible, intimate encounter with the deceased. Jane’s bright coral lips and rosy cheeks suggest youth and alertness, and her only visible blue eye gazes hopefully beyond the frame. However, the satin lining opposite Jane’s portrait adds a bittersweet undertone; a few faded lines of text hand-inked by Jane’s younger brother Robert C. Winthrop read, “My sister/Jane Winthrop/taken after/her death/by/Sarah Goodrich/1819”. Born in 1801, Jane would have only been seventeen when she passed away, making Goodrich’s vivid posthumous likeness particularly heart-wrenching.[1]

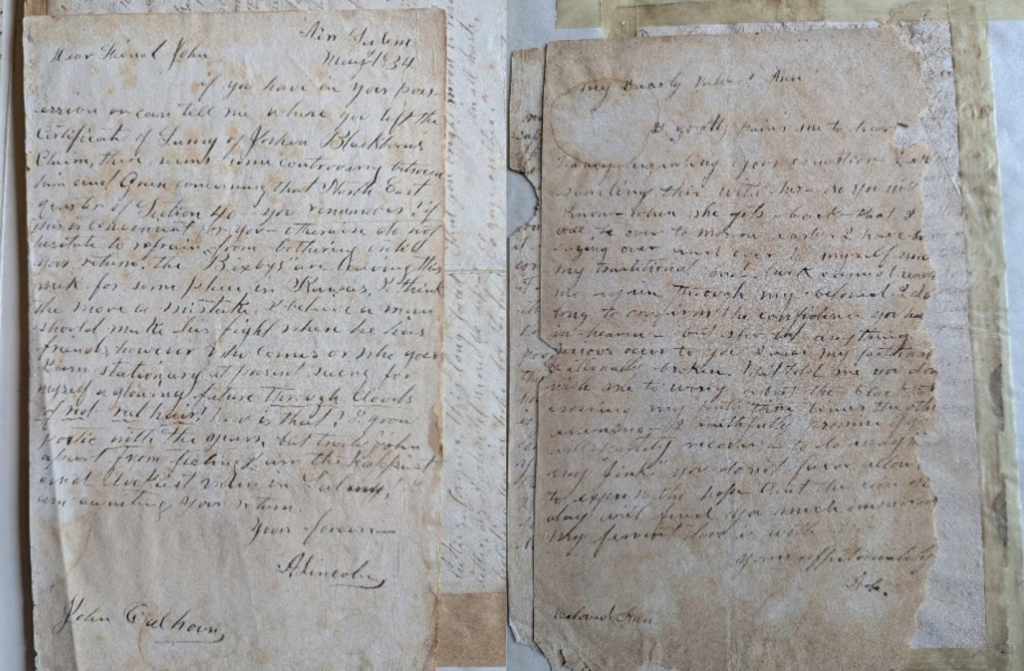

In an era before photography, miniature mourning portraits like this one served as precious reminders of deceased loved ones’ image and presence. A greater emphasis on romantic and familial bonds beginning in the late 18th century made loss harder to bear.[2] Indeed, the day after her death, Jane’s father Thomas Lindall Winthrop writes to his sister to share news of his daughter’s death, mourning “the dissolution of one of the most innocent, purest-minded, and loveliest girls that perhaps ever existed.”[3] Winthrop’s praise of Jane’s virtues conveys his love for her and reveals the grief he feels in her absence. Jane’s portrait mirrors this verbal praise; her white dress and its collar of soft, layered frills suggest the purity and grace her father lauds and whose loss finds the whole family “in great affliction”.[3] In contrast to her youthful countenance, Jane’s hairstyle suggests that she has entered womanhood since her curled bangs and pinned-up bun match the style worn by the thirty-year-old Caroline Hall Parkman in her own miniature portrait.[4]

While Robert, the portrait’s inscriber, was only nine when his sister passed, his later writings bring Jane’s portrait to life. The piano on which Jane rests her hand assumes special significance when considered alongside a memory recounted by Robert in a letter from 1877. Recalling how his “six or seven brothers and sisters used to gather around the piano”, Robert writes that this memory “brings back a family group—of which I am the youngest and now the only survivor—as vividly as I hope one day see it above”.[5] Surely viewing his sister’s portrait, with its miniature piano, would have reminded Robert both of these fond memories and the painful losses that eventually followed.

Crammed into the corner, the piano—where Jane could often be found in life—also echoes the early 19th-century idea that the process of mourning fulfilled “a fundamental need to imaginatively or tangibly locate the dead in a specific way.”[2] In the letter to his sister, Thomas Winthrop writes that he believes Jane to be “happy in another and better world”, marking his desire to cognitively pinpoint his deceased daughter.[3] Goodrich, too, positions Jane between this world and the next; even as Jane appears alive and alert, her gaze drifts beyond the piano, symbolically disconnecting her from earthly pastimes like playing music. Though Jane is unreachable in death, her presence remains accessible to her loved ones through Goodrich’s portable, intimate portrait.

[1] Shaw Mayo, The Winthrop Family in America, 218. Jane was born on March 15, 1801, and died February 22, 1819, in Boston.

[2] Jaffee Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures, 7.

[3] Winthrop, Thomas Lindall, Letter to sister Jane Stuart, February 23, 1819. It must have been a sort of cruel irony to write to one Jane that another Jane had died.

[4] Massachusetts Historical Society Online Collections page for portrait miniature of Caroline Hall Parkman. The sitter was born in 1794 and the portrait was made ca. 1824.

[5] Winthrop Jr., Robert C., A Memoir of Robert C. Winthrop, 297. Robert had 14 siblings, so to be the lone survivor is a particularly lonely position to occupy.

![A Newspaper Advertisement which reads “To be sold by John Hancock, at his store No. 4, at the East End of Faneuil Hall, A general Assortment of English and India Goods, also choice Newcastle Coals and Irish Butter, cheap for Cash. Said Hancock desires those Persons who are still indebted to the Estate of the late Hon. Thomas Hancock, Esq: deceased, to be speedy in paying their respective balances, to prevent trouble. N.B. In the Lydia, Capt. Scott, from London came the following packages 1 W No. 1, A Trunk, No. 2, a small Parcel. The Owner, by applying to John Hancock and saying [illegible], may have his goods."](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/John-Hancock-early.jpg)