by Brandon McGrath-Neely, Library Assistant

As spring arrives, the world around the MHS becomes full of life. Ellis Hall’s large windows frame Fenway’s new leaves, budding flowers, and traffic of all sorts. Any given day, you can see cars, buses, bicycles, scooters, pet strollers (my personal favorite), and on rare occasions–roller skaters.

Though roller skating isn’t as popular as it was in the mid-1990’s, it remains a popular warm weather activity here in Boston. Largely thanks to the fact that Boston, the second most walkable city in the United States, has plenty of flat, paved surfaces, but perhaps also because the inventor of the modern skate grew up nearby!

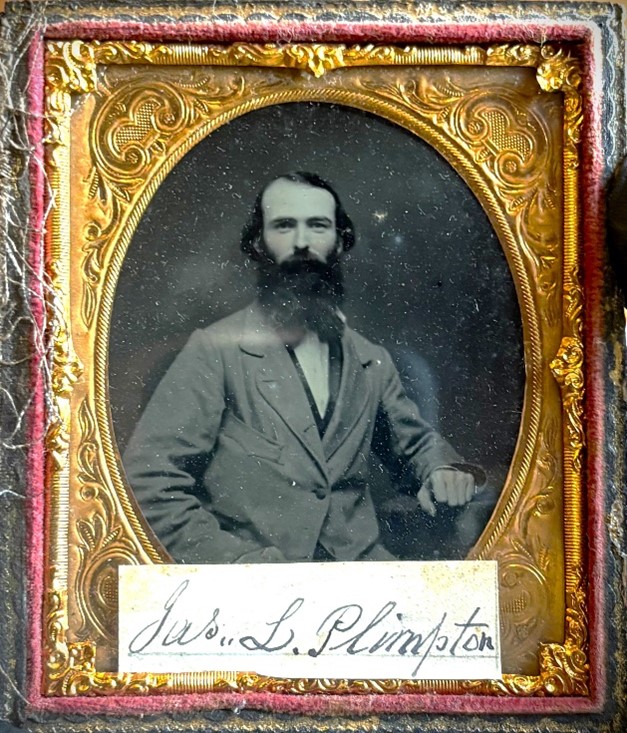

Born in 1828, James Leonard Plimpton showed an early affinity for machinery and invention. His mechanical skills were so strong that at 16, he moved from the family farm in Medfield to a machinery shop in Walpole. By 18, he supervised more than 50 employees at a factory in New Hampshire.[1] A young entrepreneur and mechanist, James was well-suited for the Industrial Revolution underway across the United States.

A tinkerer at heart, James filed his first patent in 1853. The invention was a “cabinet bed,” designed so a bed could be stored and retrieved without much strength or bending over. Sources simply note that Plimpton invented the cabinet bed “to supply a personal need,” but we may be able to guess what this need was. In December 1852, James married the bright, book-loving Harriet Amelia Adams. [1] Perhaps the newlyweds needed to save space or were preparing to add children to the home and needed a bed that would be easier for a pregnant Harriet to store. It is possible that Plimpton, in the words of Ana Ruhl, “loved her to the point of invention.” They would go on to have eight children together; only four lived to adulthood.

Around 1860, James and Harriet moved their family to New York City. The MHS collection has a single image of James Plimpton, probably taken shortly after arriving in the Big Apple. He gives the appearance of a hopeful, determined man. Within a year, James took ill. Consulting a doctor, James “was advised to practice ice skating,” and happily, James “took much benefit from it.” [2] Like many Northeasterners, James grew up ice skating in the winters. (The MHS has many materials about ice-skating, including a heroic rescue.) When spring arrived and the ice melted away, James purchased an early pair of roller skates.

Yes, roller skates existed before James Plimpton’s came along. The first recorded use of roller skates was “in a 1743 theater production in which actors affixed wheels to their footwear to mimic ice skating on the stage.” [3] Early roller skates were commercially available by the mid-19th century, but they were uncomfortable, awkward, and difficult to turn. They didn’t feel like ice-skating at all. After some experimenting and tinkering, James produced a new set of roller skates with two pairs of wheels, called “rockers” or “quad-skates.” [4] These new skates were more comfortable and far easier to turn. The modern roller skate was born.

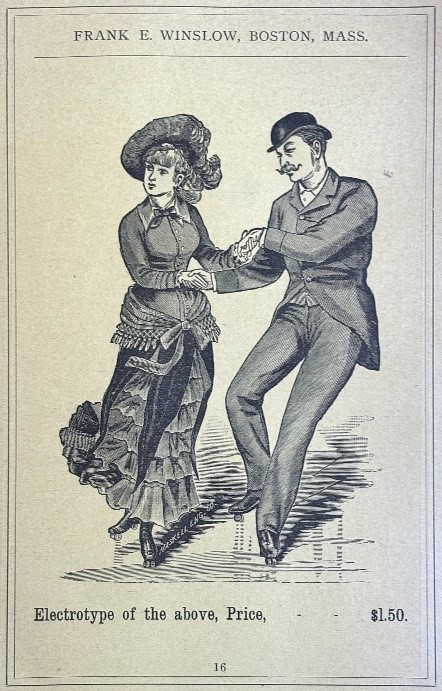

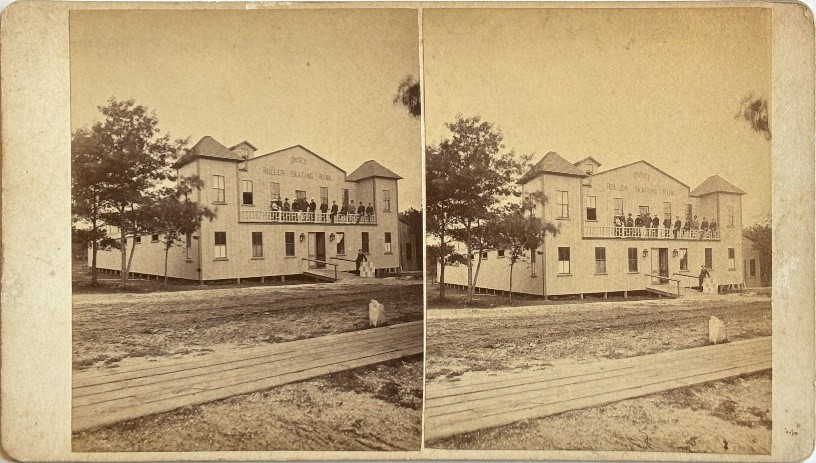

The invention was a giant success. Advertisements boasted that Plimpton’s skates were “the only one upon which all the graceful movements and evolutions of Ice Skating can be executed with ease and precision on a Smooth Floor.” [5] The MHS collection has plenty of evidence of this phenomenon: admittance tickets to roller skating rinks, skate advertisements and catalogues, bookplates, and photos of popular roller-skating clubs. Senior Processing Archivist Susan Martin has written about Great Depression-era debutantes making appearances by skating around town.

James Plimpton spent the rest of his life selling, improving, and litigating his patents. Harriet was a caring mother and educator to their children, as well as an irreplaceable business partner. “Her quick perceptions and correct impressions as to social, legal and business points” ensured that she could “give her husband that assistance in the preparation of his patent cases that could not otherwise have been as thoroughly prepared within the time required.” [6] Roller skating was a family business and only possible through the hard work and intelligence of both Harriet and James.

The roller-skating crazes of the late 19th and 20th centuries have come and gone. Hoverboards, Onewheels, and E-bikes have replaced them on the sidewalks of Boylston Street. But occasionally, if you’re lucky, you may look out the windows of Ellis Hall and see a piece of Massachusetts history skate past you.

[1] Chase, Levi B. 1884. A Genealogy and Historical Notices of the Family of Plimpton or Plympton in America, and of Plumpton in England. Hartford: Plimpton Manufacturing Company. 196-197.

[2] “The Father of Modern Roller Skating.” 2023. National Museum of Roller Skating.

[3] Terry, Ruth. 2020. “The History Behind the Roller Skating Trend.” JSTOR Daily, September 7, 2020.

[4] “The History of Inline Skating.” 2023. National Museum of Roller Skating. 2023.

[5] MacClain, Alexia. 2010. “Those Exhilarating Roller Skates.” Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. September 27, 2010.

[6] Chase, A Genealogy and Historical Notices, 196-197.