Maggie Parfitt, Visitor Services Coordinator

I want you to imagine the work of an 18th century American woman. What is she doing? Is she sewing and cooking and cleaning? Does she leave her home for work?

Now I want you to ask yourself where that image came from—what conjured it in your mind?

In historical anthropological theory there’s a recognition of recency bias—our understanding of the past is informed by our assumptions about our present. This is complicated in the West by our beliefs about linear “progress.” We’re apt to believe current Western society is “the best it’s ever been” and our modern inequities are deeply rooted in history—progress necessitates as such.

Working in public history I run into the same fallacy again and again, especially when discussing Western women’s lives in the 18th century and earlier. Believe it or not, most strict Western gender roles don’t come from centuries long history of labor separation. Instead, most are rooted in the late 19th and early to mid-20th century (recent, by history standards!). As a quick example: the average marrying age of English women during the first half of the 18th century was 26[1], in 1850 America it was 23[2], and in 1960 it was around 20.[2]

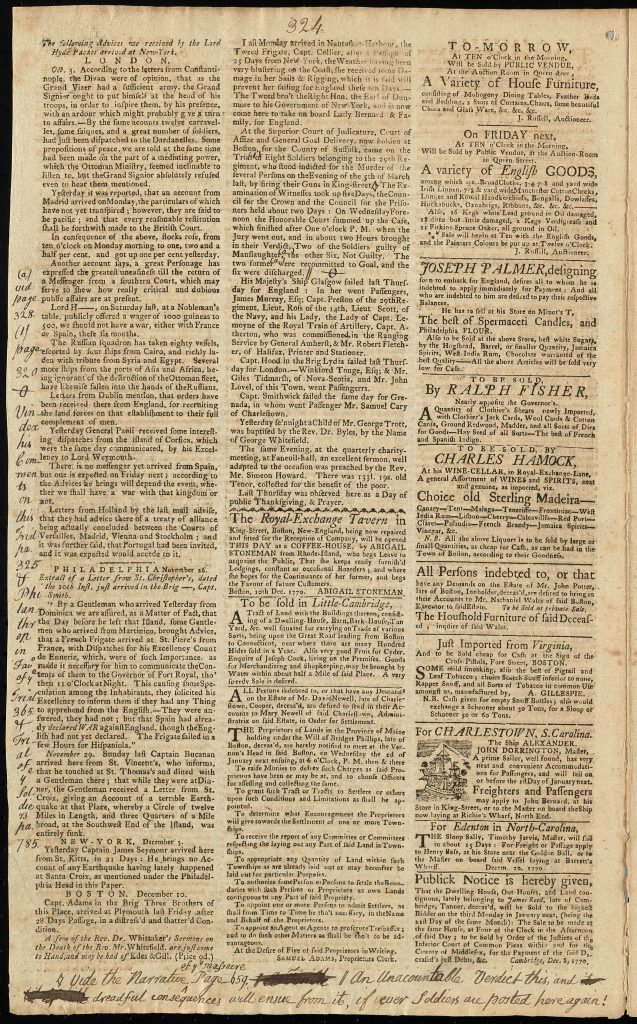

Now that we’ve reset our assumptions, what can we learn about how and why women worked in 18th century Boston? Newspapers are a valuable tool, giving us a peek into daily 18th century life. Browsing the advertisements in the Harbottle Door Annotated Newspaper Collection reveals many examples of the ways 18th century women supported themselves, their families, and their community. While reading and sorting through clippings I noticed women earned money in roughly three ways: through entrepreneurship, wage work, or indenture.

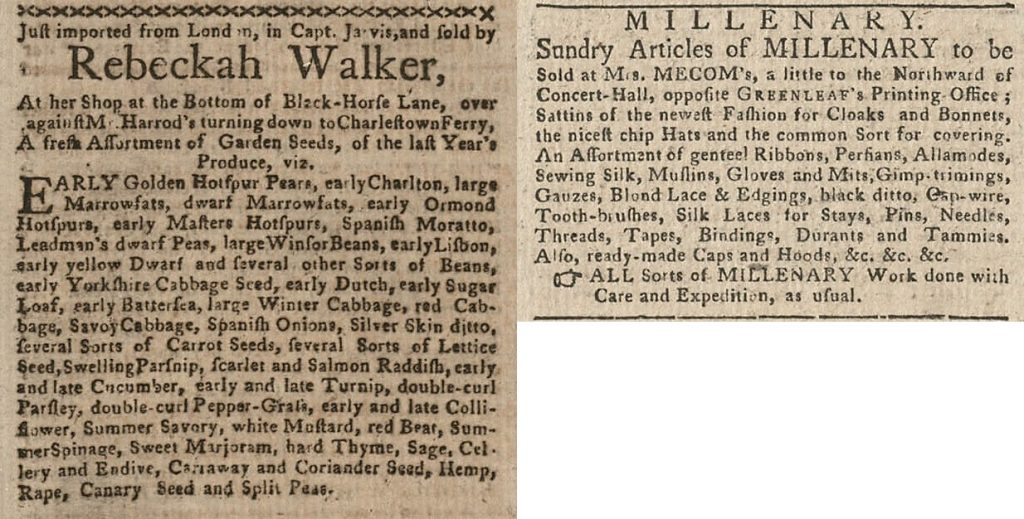

While outnumbered by advertisements for male-operated businesses, it’s not uncommon to see women advertising their wares, often in their own shops!

In her study of women’s labor in 18th century cities Karin Wulf found women were more likely to operate businesses relating to “domestic labor” like sewing or cooking. [3] Mrs. Mecom’s millenary business falls into this category. This is not to say that women were confined to gendered businesses—women like Rebeckah Walker operated all kinds of businesses in all kinds of fields. Neither were women limited to retail. Women frequently placed ads for their service-based businesses ranging from teaching to operating taverns and coffeehouses.

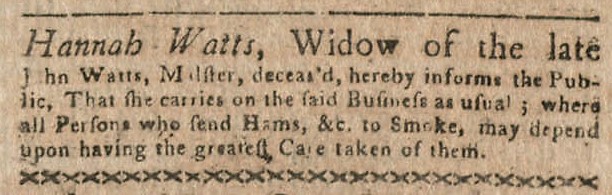

Women most often came business after their husband’s death. Upon being widowed, if the husband’s estate was uncomplicated (which typically included those in the merchant class or lower) the sole ownership fell to their wife, who could then choose to carry on the business.[3]

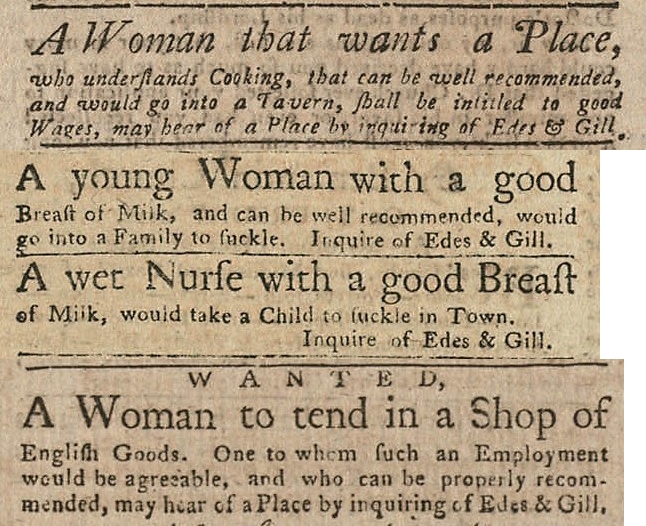

The second category of paid women’s work is wage work—what we would probably think of as regular employment or gig work, depending on the situation. Many but not all of these jobs also fell into domestic labor categories including household management, laundry, and wet nursing (which seems to be a whole separate industry![4]).

The third category is by indenture, where women signed a contract and in exchange received wage, food, and lodging. While certainly not all rosy, Kent’s research on female domestic servants in 18th century London suggests some young single women preferred indentured contracts to other forms of wage earning. Women earned about 1/3 the amount a man would earn for day labor, and the pattern holds even when comparing skilled trades, like a mantua-maker (dressmaker) to a tailor (men’s suits and clothes). Non-indentured working women often barely made enough money to cover housing and meals. An indenture contract came with “diet and lodging” included, meaning indentures were one of the few ways women could earn disposable income.[1]

![A clipping from the Boston-Gazette and Country Journal. The advertisement reads “to be sold on board the sloop London Expedition, Nicholas Chevalier, Master, laying at Wibert’s Wharf, New-Boston. A Number of Indented [Indentured] Jersey Servants of both sexes: Likewise a quantity of cordage of all sorts, and hosiery.](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/indented-servants.jpg)

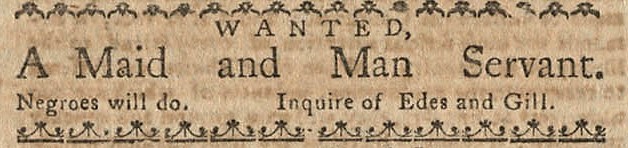

We can’t talk about the ways women provided for themselves without acknowledging the ways women were denied control of their own livelihood. You cannot look through an 18th century newspaper without directly confronting the flippancy of enslavement and the dehumanization of Black people, free and enslaved.

While beyond the scope of this blog post, I encourage you to learn more about enslavement in Boston by reading Dr. Jaime Crumley’s blog post on the enslaved parishioners of Old North and The City of Boston Archaeology Program’s “Boston Slavery” online exhibit.

Married women, while part of a partnership, were still subject to the whims of their husbands.

![Two clippings from the Boston Gazette and Country Journal. In the first Isaac Kingman “warn[s] all persons not to trust [his wife Ruth Kingman] on [his] account also to forbid all persons trading with her or purchasing any of my goods or chattels of her” in response to her “refus[ing] to remove and live with me as she ought to do.” In the second a husband forbids people from “trusting [his wife Sarah] on [his] account” as she “hath behaved in a vile manner, keeping company with wicked men.”](https://www.masshist.org/beehiveblog/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Wayward-Wives-1024x285.jpg)

While these ads paint a bleak picture, most of the time an 18th century husband was not the sole controller of the household, financially or otherwise. Karin Wulf calls the 18th century urban landscape one of financial “interdependence” rather than independence[3]. Both sides of the relationship entered a marriage with financial value, and both had to work to secure economic stability. Eliza Haywood wrote in 1743/44 London “You cannot expect to marry in such a Manner as neither of you shall have Occasion to work, and none but a Fool will take a Wife whose Bread must be earned solely by his Labour and who will contribute nothing towards herself.[4][1]”

[1] Kent, D. A. “Ubiquitous but Invisible: Female Domestic Servants in Mid-Eighteenth Century London.” History Workshop Autumn, 1989, no. 28 (1989): 111–28.

[2] Fitch, C., & Ruggles, S. (2000). “Historical Trends in Marriage Formation: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation.” In L. Waite, C. Bachrach, M. Hindin, E. Thomson, & A. Thornton (Eds.), Ties that Bind: Perspectives on Marriage and Cohabitation (pp. 59-88). Aldine de Gruyter.

[3] Wulf, Karin. “Women’s Work in Colonial Philadelphia.” In Norton, Mary Beth., and Ruth M. Alexander (Eds). Major Problems in American Women’s History : Documents and Essays. 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003.

[4] Shepard, Alexandra. “Working Mothers’ in Eighteenth-Century London”, History Workshop Journal, Volume 96, Autumn 2023, Pages 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbad008