by Susan Martin, Senior Processing Archivist

While processing the MHS collection of Huse family papers, the following letter caught my eye, for obvious reasons.

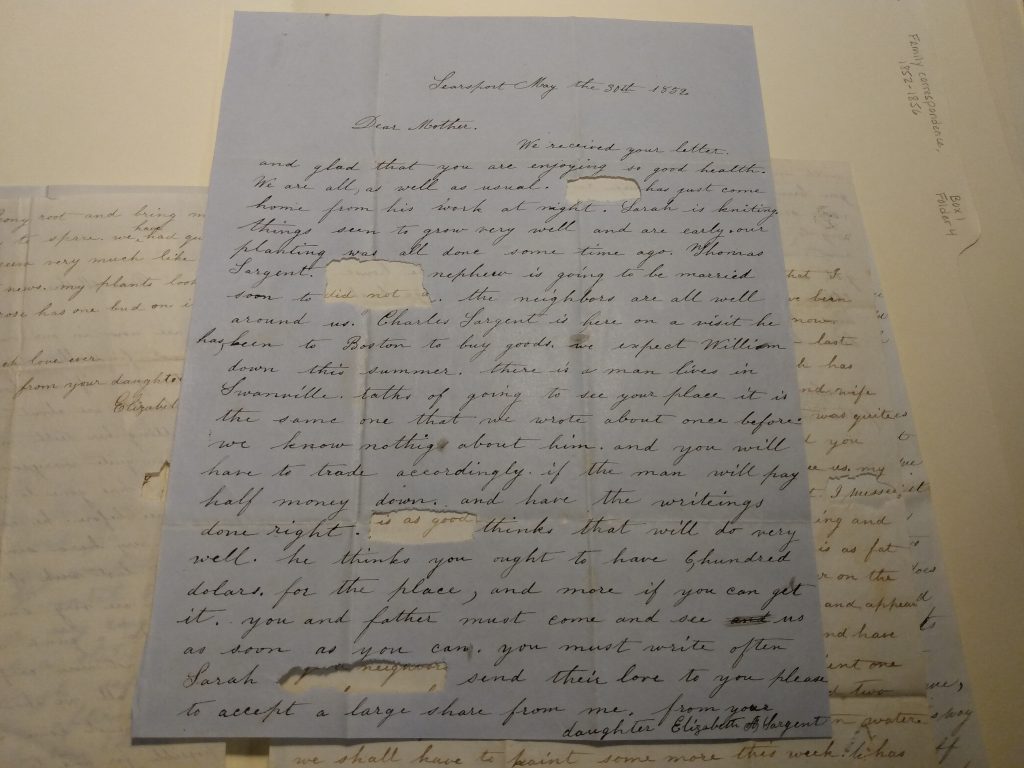

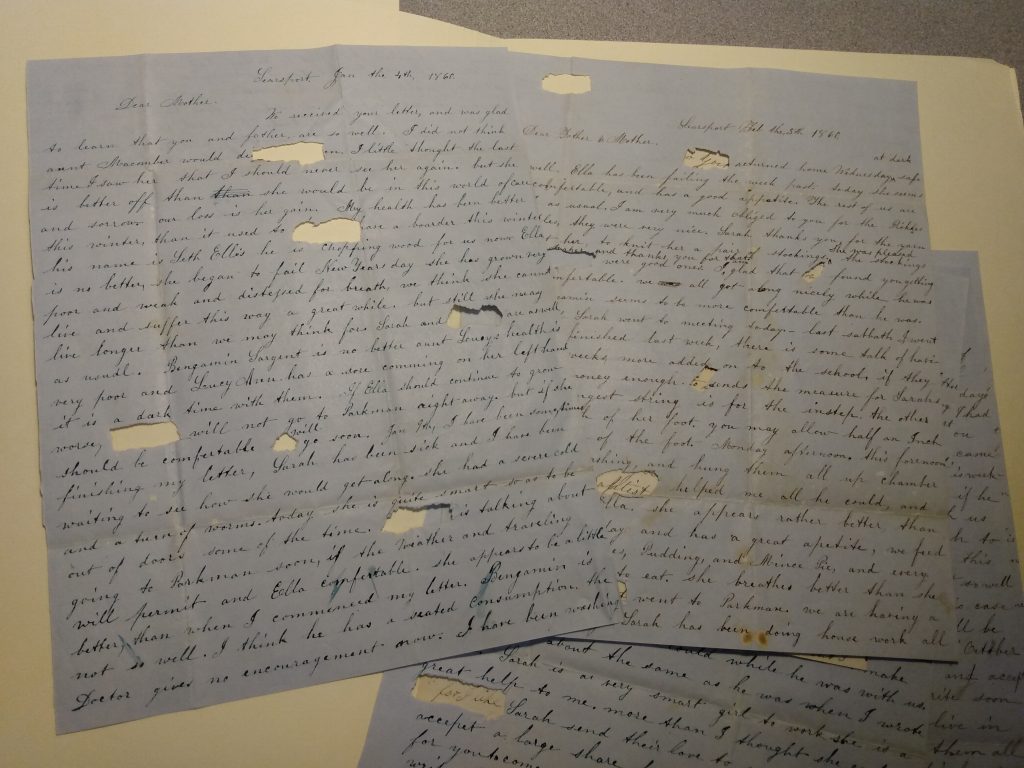

This letter was written by Elizabeth “Lizzie” (Fuller) Sargent to her mother Sarah Fuller. For some reason, everywhere Lizzie mentioned her husband Samuel, his name had been physically removed from the letter. “Hmm, that’s interesting,” I thought, and carried on processing. Then I noticed several more.

Something weird was definitely going on here. Nearly every letter from Lizzie to her mother got the same treatment. For example, “[?] sends his love with mine to you all”; “[?] has gone to meeting at the village this afternoon”; and “This is Saturday evening and [?] is oiling his harness and Sarah is rocking the cradle.” From context, it’s clearly her husband’s name that’s missing, and sometimes apparently just his initial!

I’ve occasionally seen words physically removed from letters, but only by a military censor or an aggressive autograph collector. This is obviously different. My first thought was that Samuel did something that landed him in the doghouse. It reminded me of cutting someone out of a photograph after a bad break-up. Had there been a divorce or separation?

Hoping to solve the mystery, I started researching the family, primarily using online genealogical resources. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to find very much. Lizzie was born in 1827, the daughter of Sarah (née Austin) and Thomas Fuller, a Maine shoemaker. In 1849, she married Samuel Winthrop Sargent, who was twelve years her senior. They lived first in Charlestown, Massachusetts, and later in Searsport, Maine.

The Sargents appear to have been a typical 19th-century family. Samuel worked as both a brick mason and a farmer, while Lizzie stayed home with the children. Sadly, of their five children, only two—Sarah and George—survived to adulthood. On 1 July 1861, Lizzie wrote this passage after losing her third child.

It is with a sad and heavy heart that I write you, again. tears almost blind my eyes. Death has visited us once more, and taken our dear little Ella. she died this morning 25 minutes past 4. it seems as if I cannot be reconciled. O pray for me, that I may not lose my reason […] my home seems, desolate now.

As far as I can tell, Samuel and Lizzie never lived apart. He died in 1901, and she lived until 1903. They and several other relatives are buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Searsport.

The collection also contains correspondence from Lizzie’s brother and sister-in-law, Andrew and (yet another) Sarah. Their story is compelling. Andrew, feeling “discontented” and “miserable” and wanting a change, joined the California Gold Rush of 1849. During his absence, his wife was desolate: “There is an acheing void […] I wonder when I eat what he has got to eat and when I go to bed what he has got to sleep on.” Andrew apparently died out west sometime in 1851, but I couldn’t confirm the circumstances. His wife Sarah remarried a few years later—believe it or not, to a man named Samuel!

While I enjoyed learning these details about the family, in the end I found nothing that accounts for the redactions. I don’t even know who was responsible for them. Was it Lizzie? Her mother? Someone else entirely? Did they happen at the time or later? Muddying the waters more, in a few instances, the name of another person was also removed. Perhaps an archival colleague or intrepid researcher out there has seen this sort of thing?

Whatever the answer, these letters are a good example of manuscripts that are interesting not just for their content, but as historical artifacts in and of themselves.