Hannah Goeselt, Reader Services

Commonwealth Avenue: that grand road snaking its way out of Boston and into the adjoining city of Newton, an eleven-mile stretch of boulevard from the Public Gardens to Auburndale-on-the-Charles, where it abruptly ends at the juncture of I-90 and I-95. At its head is Commonwealth Avenue Mall, a picturesque greenway home to an array of statues of historical figures leading up to the Garden’s entrance.

Gazing dramatically into the shadows of an overpass, Leif Erikson, dressed in a short chainmail tunic straight from the nineteenth-century imagination, looks practically glamorous posed with fist planted on his hip, bronze locks billowing behind him. Originally marking the end of the Mall, the statue relocated to nearby Charlesgate in 1917, and a stone’s throw from the MHS.

In our most recent podcast episode, “Events That Did Not Happen”, Peter Drummey and Dr. Kanisorn Wongsrichanalai sit down to discuss the origins of the statue, and how the MHS fits into its narrative.

The Norsemen Memorial

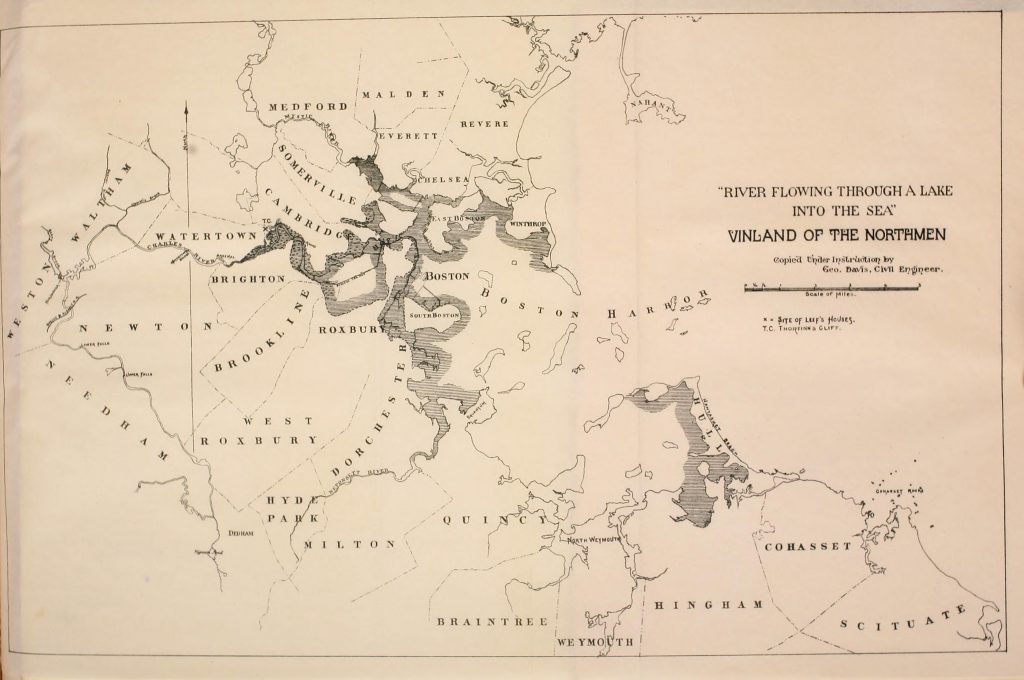

This all began in December of 1876, during a reception honoring the Norwegian violinist Ole Bull1, in which Rev. Edward Everett Hale proposed a tribute to Bull’s devotion to the city and the formation of a “committee of the Norsemen Memorial”. The goals of the committee were twofold. 1) to erect a monument commemorating the Norse discoverers of America, and 2) the preservation of Dighton rock (including briefly gifting it to Denmark)2. The committee was full of prominent Bostonians such as Governor Alexander Rice and Mayor Samuel Cobb, but the one that would come to be emblematic of this whole affair was Eben Norton Horseford (whose life is better outlined in the podcast), a former chemistry professor made wealthy by his patented Rumford baking powder.

In 1880, Hale’s cousin, William Everett, brought the matter of the committee and the statue to the MHS: “I desire, sir, to call the attention of the members to a scheme which is assuming somewhat serious proportions; in which, if it is really judicious, the Historical Society ought to help; against which, if it is otherwise, it is our duty to protest. I mean the scheme for erecting a monument to some person called the first discoverer of New England; not, however, John Cabot, or Sebastian Cabot, or Verrazzano, but an indefinite Northman, to whom, if I may be allowed a very bad pun, it is proposed to put up a Leif statue.”3

The next time the statue was mentioned was at the November 18874 meeting, at which time a committee was selected to have a final word on the validity of the statue, which had by then been unveiled with great celebration the previous month. By December, there was a verdict: “there is the same sort of reason for believing in Leif Erikson that there is for believing in the existence of Agamemnon. They are both traditions accepted by the later writers; but there is no more reason for regarding as true the details related about his discoveries than there is for accepting as historical truth the narrative contained in the Homeric poems.”

To be Continued…

1 Bull was a strong proponent of Carl Christian Rafn’s theories of Vikings discovering America before Columbus, a theory which had been published earlier in the century to wide interest. Much of Bull’s feelings on the matter are expressed in his memoir written posthumously by his wife, Sara Chapman Bull, a resident of Cambridge (see pp.270-76 of the memoir for details of the statue committee’s creation).

2 I first saw an account of this in the ‘preface to the new edition’ of Rasmus Bjorn Anderson’s America not discovered by Columbus, 1877, which proved to be interesting on its own, as this particular copy was also inscribed on the front flyleaf: “Mr. Mauk, from his devoted friend and admirer Ole Bull Cambridge Nov 1879”, with a second inscription made “To Francis R[ussell] Hart Esq. With kindest regards Olaf Olsen, Oslo 1930”.

3 Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society [First Series], vol. XVIII (May 1880), p.79-81. The pun, as best I can tell, is based on an archaic verb usage of the word “leif” to mean ‘willing’ or ‘glad’.

4 Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Second Series, vol. IV (November-December 1887), p.12, 42-44.