By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

The Massachusetts Historical Society will be closed Saturday, May 25th and Monday, May 27th in honor of Memorial Day, so I thought I would look at some of the ways people have celebrated this day in the past. One popular way was by listening to speeches highlighting the importance of Memorial Day and why it mattered. Referred to as “Memorial Day Addresses” in our catalog, these speeches were a way to remind people exactly what the day was about. Memorial Day finds its origins in Reconstruction, the time after the Civil War. It was originally referred to as “Decoration Day” and centered around visiting the graves of loved ones who died in the Civil War and enjoying a picnic afterwards. This tradition was kept alive in the popular barbecues of my childhood, though without the graves. Traditions have certainly changed but it’s always interesting to look back at a snapshot of time and see what changed and what remained the same.

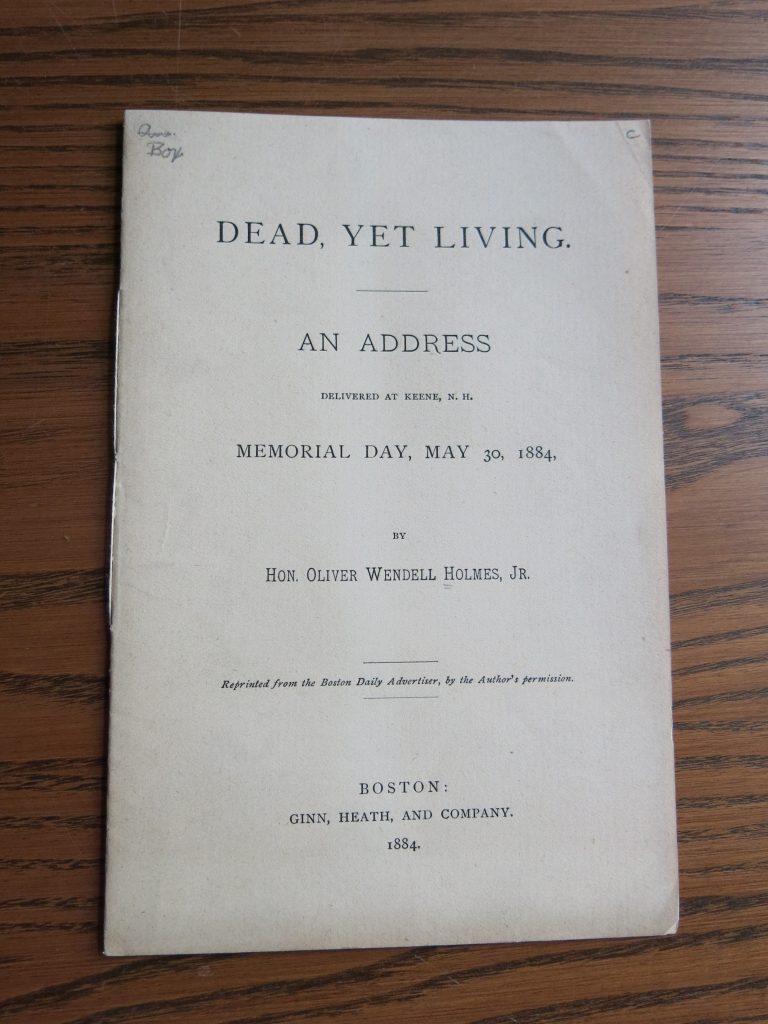

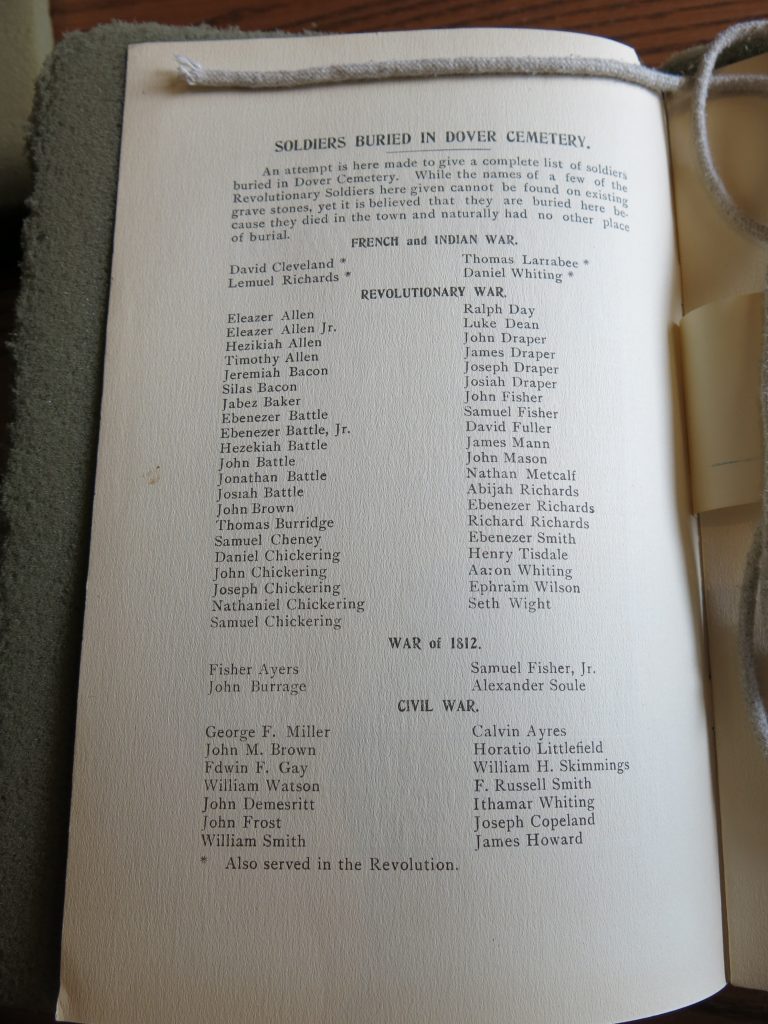

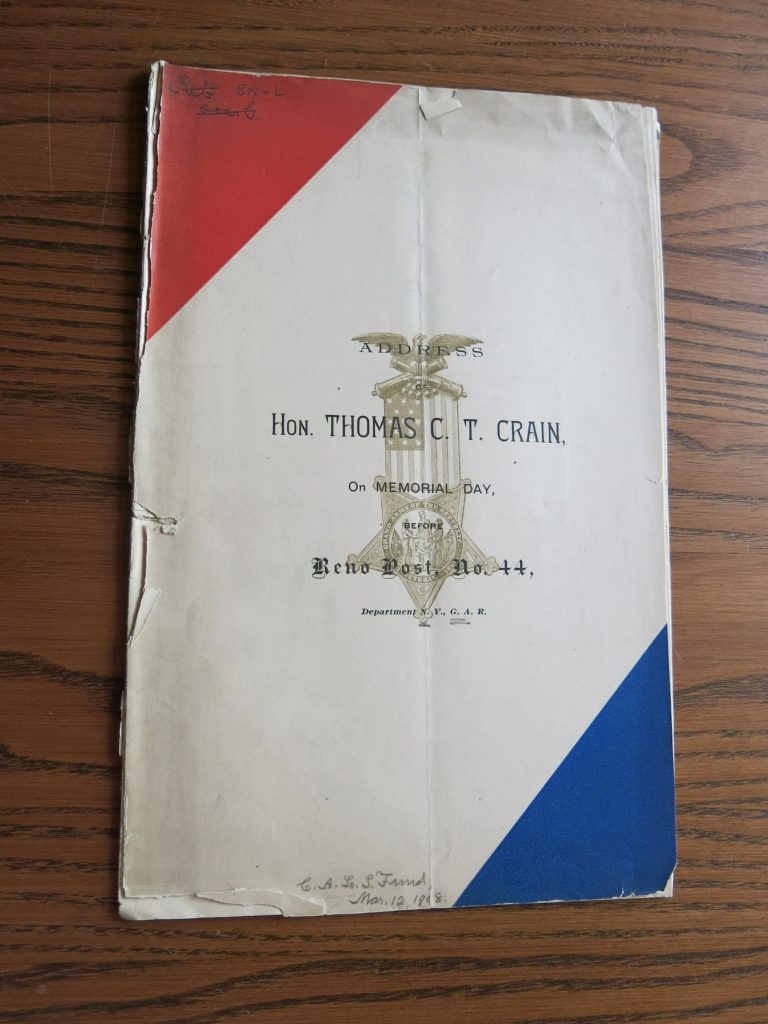

While today Americans tend to associate Memorial Day with more modern wars with still living veterans, the addresses I looked at, from 1881 to 1904, tied the holiday explicitly to both the then-recent Civil War and to the American Revolution. Many of them linked back to what were considered the origins of the United States and the founding principles. Reading through the addresses, many speakers viewed the wars America had fought as part of a tradition of patriotism and strong morals. Nowhere is this more evident than in Frank Smith’s 1904 address in Dover, Mass., which outlines in almost excruciating detail every war or conflict the town had sent men to, from fighting the indigenous peoples to the Spanish American War, in 1898. The published speech also includes a list of the soldiers who had died and were buried in the Dover Cemetery, a demonstration of the honor Smith felt they deserved. The connection between war and patriotism is made over and over again in these addresses, despite ostensibly praising and honoring peace.

That patriotism covers more than just the Union itself though. Most of the speakers also strongly tie these actions to the character of the region. This pride in being New Englanders is a key part of the argument these speakers are making—that these wars demonstrate the superiority of American ideals and that nowhere are these ideals more truly upheld than here. This call to sacrifice includes both men and women, though in very different ways. The picture of the idealized soldier in most of the speeches is a striking one. He is brave, strong, and true, the perfect specimen, willing to die. And the women take care of the home, work in the jobs that are left behind, and mourn the men who die on the battlefield. The men die and the women suffer. These addresses remind listeners to do their duty and do it faithfully, regardless of the cost.

There is a somberness to these addresses, but that is tempered by the sense of how honorable it is to fight and die in a war. This view of war is contradicted in our own collections, however. Susan Martin writes here and here about veterans who disagreed with the way the Revolution was commemorated, an interesting counter to the lofty language and ideals expressed by the speakers even within a similar time period.